In the annals of Australian exploration, one name stands out with unwavering resilience and a spirit of adventure that pushed the boundaries of human endurance. Tim Macartney-Snape, a renowned mountaineer and adventurer, etched his name in history through his extraordinary feat in the 1984 Australian Expedition.

This expedition, a daring and audacious undertaking, saw Macartney Snape conquer the unforgiving terrain of the world’s highest peak, Mount Everest, in an epic journey that captured the imagination of a nation. Join us as we delve into the gripping tale of courage, determination, and a relentless pursuit of conquering the impossible, as personified by Tim Macartney-Snape and his legendary 1984 Australian Expedition.

Beginning of the Australian Expedition

At camp one on September 27th, the weather was cold and clear. The climbers were pleased that the wind had ceased, but they opted to stay put rather than climb to camp two and risk being foiled by a sudden change in the post-monsoon winds. A prolonged spell of calm weather was what they needed. Despite the uncertainty, the group was enthusiastic and determined as they ascended the neve of the Rongbuk Glacier towards the face and the beginning of the fixed ropes. Hall’s return to the team after recovering from his respiratory ailment significantly boosted morale, and his experience and skill were vital to their small and vulnerable group.

The team arrived at camp two, settled into their snow cave for the night, and planned to tackle White Limbo and the Great Couloir the next day. However, their hopes were dashed once more by the weather. Throughout the night, the wind grew stronger, howling across the North Face of Everest. They hesitated to retreat to camp one, knowing that the constant back-and-forth trips depleted their energy. They feared descending this time might leave them insufficient power to climb back again.

Read more: 1963 American Mount Everest West Ridge Expedition

Morale Began To Decline As Days Dragged On

As the enforced rest days dragged on, morale began to decline. Hall believed that failing to climb a mountain due to technical difficulty or inadequate strength was acceptable, but returning home without attempting to reach the summit because of unfavorable weather conditions was intolerable. After three days of inactivity at camp two, the team’s burning drive to succeed in adversity began to wane.

After a windy night on the north side of Everest, the five climbers were surprised to find that the wind had died in the morning. They took advantage of the lull and ascended higher up the mountain, following the ropes fixed on White Limbo. Although the snow had consolidated, the climb was slow and difficult due to the climbers’ weight and heavy packs. Bartram’s summit attempt was cut short when he began experiencing symptoms of cerebral edema, a serious condition that can be fatal if not treated promptly. Bartram quickly diagnosed himself and descended to camp two, leaving his communal gear to Henderson. The mountain was already starting to reveal the eventual summit team.

The White Limbo

As the afternoon progressed, the team reached the end of the fixed ropes at the top of White Limbo, retrieved their gear that had been stashed there weeks earlier, and began crossing the slopes towards the Great Couloir. It was an enjoyable day of climbing, and having ascended over 600 meters, they came across a natural snow cave formed by a partially open crevasse, which provided them with a place to sleep.

The following day brought gentle gusts of icy wind, but they were nothing like the continuous gales from earlier. This signaled the arrival of a period of decent weather, which was the break the climbers had been waiting for. Slowly, the team began the exhausting haul up the Couloir.

Although the climb was not technically challenging, it was certainly not without danger. The angle of the face was around forty-five degrees, not steep enough to require a rope and belay. The snow was firm, almost icy, which made it perfect for crampons. However, the hard snow also meant that any slip or fall could be fatal. A sliding climber would have little hope of using their ax to stop their fall.

Despite its spectacular position and awe-inspiring views, climbing the Great Couloir had few elements of pleasure, as Hall recalled.

Read more: Mount Everest’s Rainbow Valley: The Mountain’s Dark Side

Passing Through The Great Couloir

As the temperature dropped and the afternoon progressed, Macartney-Snape and Mortimer searched for a suitable campsite near the top of the Great Couloir. Unfortunately, they couldn’t find a ready-made snow cave and had to settle for an angled spur to pitch their tent. The climbers consumed liquids and food despite the challenging conditions to maintain their strength. They had reached a height of approximately 8,150 meters that day, the highest any of them had ever been, well within the death zone.

The following morning, the weather was stable, and the winds were calm. It was October 3rd, 1984, more than 62 years after Australian George Ingle Finch attempted the same area. Mortimer, Macartney-Snape, and Henderson, numb from the cold and slowed by the lack of oxygen, led the way. The climbers had to traverse across the width of the Great Couloir and up toward the rock band that blocked the top of the Couloir. The climbing was straightforward, but it was painfully slow at that altitude. Since the rock band was in deep shade and would remain cold throughout the day, the climbers decided to traverse over to the Yellow Band, which was in the sun.

After reaching the Yellow Band, Tim Macartney-Snape became the leader and began climbing a natural ramp, a tricky combination of rock and ice that he described as “bad snow on poor rock.” Climbing higher beyond the ramp proved to be hazardous, and Macartney-Snape secured Mortimer by dropping a rope to assist him in the climb up the steep rock section. Unfortunately, by the time Henderson arrived, Macartney-Snape and Mortimer were too far ahead to offer additional support, and Henderson had to climb the area alone.

Meanwhile, Hall had decided to turn back. Despite being the last to leave the tent, he had taken his time crossing the Couloir and had begun to feel that his body was not warming up. Hall had been struggling with cold hands and feet throughout the climb and did not want to risk frostbite again, given his experience of losing two toes after spending two nights on the summit ridge of Doonagiri six years prior.

After conquering their biggest challenge at the Yellow Band, Macartney-Snape and Mortimer faced a draining battle against fatigue, lack of oxygen, and fading light. Even though the summit was within reach, time was rapidly running out, which made the climb much more challenging.

Read more: Why Do People Keep Dying on Mount Everest?

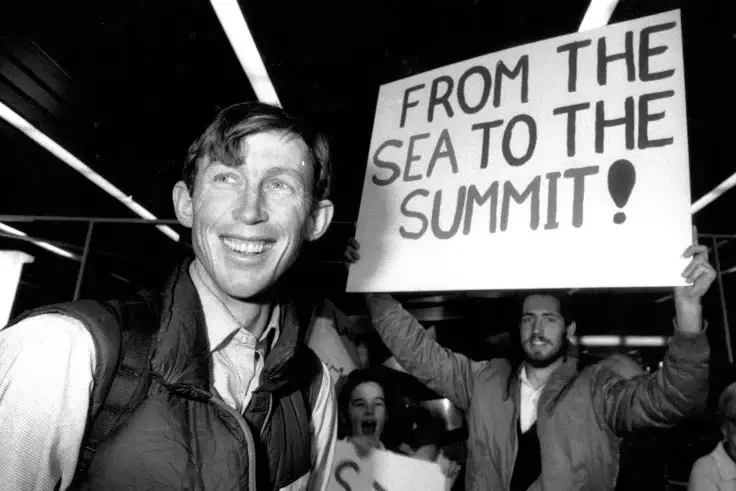

Tim Macartney Snape: From Sea To Summit

As the sun set, Tim Macartney-Snape accomplished the remarkable feat of becoming the first Australian to reach the summit of Mount Everest. Greg Mortimer soon joined him, but Macartney-Snape’s achievement was impressive because most climbers could barely function upon reaching the summit. Macartney-Snape even carried a movie camera and tape recorder and made a speech about the environment and nuclear war. However, Henderson had to stop just short of the summit due to a broken crampon, which he had to repair at the cost of frostbite, resulting in losing his fingers.

Descending from the summit was perhaps even more challenging for the trio, especially in the extreme cold and darkness. They managed to traverse to the top of the Great Couloir but had no snow stakes to anchor their descent. Macartney-Snape improvised by using an aluminum stave from Mortimer’s pack, burying it in the snow to serve as an anchor.

After their grueling climb, the three climbers stumbled into the tent, with Henderson arriving last. They were all exhausted and had difficulty with even the most mundane tasks. They hugged and shed tears of joy and relief, but Henderson’s severely frostbitten hands dampened the celebrations.

Descending The Summit Was A Struggle for Tim Macartney-Snape and team

The next morning, the team realized the precarious situation they were in. Macartney-Snape could descend on his own, but Mortimer and Henderson needed help. The team packed Henderson’s gear and divided his belongings, preparing him for the descent. Although Henderson’s hands had frozen in a gripping position, they were pried open easily to insert the ice ax, and he could descend without further assistance.

Mortimer, however, was in serious trouble. He was semi-conscious and unable to prepare himself to descend. Hall and Macartney-Snape had to attach crampons to his boots, but he moved slowly due to exhaustion or cerebral edema. Hall began the descent with Mortimer, but Macartney-Snape soon overtook them. They eventually settled for a night in the crevasse above the ice cliffs.

The next morning, Mortimer was slightly better and could prepare himself for the day’s climbing. He set out before Hall for the traverse across White Limbo, and the descent went without incident. By nightfall, Hall was back on the glacier with Colin Monteath. Mortimer was just above on the fixed ropes, and Henderson had already descended from camp two. Macartney-Snape had climbed down from camp four to the glacier and camp one in a single afternoon. The ordeal was over for everyone except Henderson, who later lost parts of all of his fingers.

The 1984 Australian Expedition Ended With Success

The Australian expedition’s ascent of Mt Everest was exceptional in many ways. They climbed the world’s highest peak cleanly and stylishly, without supplemental oxygen, and even established a new route. Macartney-Snape and Mortimer’s summit climb exemplified near-ideal alpine style, with only one camp set on the North Face and most of what they needed for the summit attempt carried on their backs.

Despite the difficulties, the Australian climbers accomplished a phenomenal achievement. Of the five climbers who set out from Sydney, two reached the summit, one came close, one climbed beyond the highest camp, and only one failed to get within striking distance of the summit. This was a remarkable accomplishment, especially considering the usual attrition rate due to illness, fatigue, burnout, and altitude sickness on Everest.

FAQs: Tim Macartney-Snape and The 1984 Australian Expedition

Tsewang Paljor, famously known as “Green Boots” on Mount Everest, has rested in the mountain’s embrace for nearly two decades. Positioned near the summit of Everest, his presence has inadvertently become a somber guidepost for those venturing to conquer the majestic peak from its north face, leaving a lasting impression on climbers worldwide.

In the year 1990, Macartney-Snape achieved a groundbreaking milestone as the pioneer who trekked and scaled from sea level all the way to the summit of Mount Everest. His remarkable feat marked an unprecedented accomplishment, solidifying his place in history.

On October 3, 1984, a significant moment unfolded as Tim Macartney-Snape and Greg Mortimer etched their names in history by becoming the first Australians to conquer the summit of Mount Everest.

Up until July 2022, a staggering number of approximately 11,346 successful summit ascents have been recorded, accomplished by a total of 6,098 individuals.