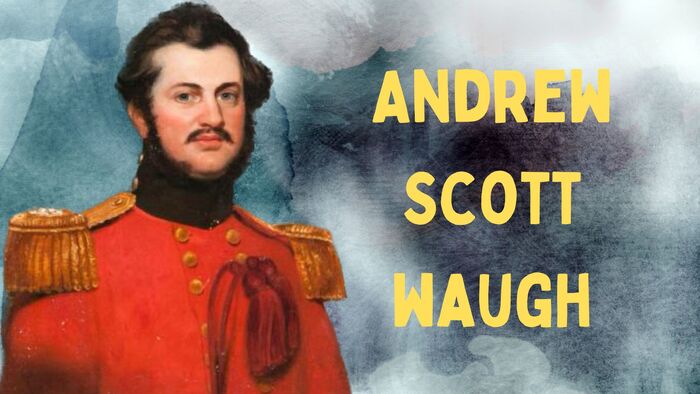

Major General Sir Andrew Scott Waugh, (3rd February 1810 – 21st of February 1878), was a distinguished British army officer and Surveyor General of India, actively involved in the Great Trigonometrical Survey.

Having served under Sir George Everest, he took over as his successor in 1843. Waugh’s remarkable contributions include the establishment of a gridiron system of traverses, effectively covering vast areas of northern India. Additionally, he is prominently recognized for bestowing the name “Mount Everest” upon the peak that now stands as the world’s highest point.

Early Life of Major General Sir Andrew Scott Waugh

The first-born of General Gilbert Waugh, who held the position of military auditor-general in Madras, was none other than Waugh himself. After completing his studies in Edinburgh, he enrolled at Addiscombe Military Seminary in 1827 and received his commission with the Bengal Engineers on the same year. Under the tutelage of Sir Charles Pasley at Chatham, he honed his skills before embarking for India in May 1829.

In his initial endeavors, Waugh collaborated with Captain Hutchinson to establish a foundry at Kashipur. Soon after, on the 13th of April 1831, he assumed the role of adjutant of the Bengal sappers and miners. The following year, in 1832, he was assigned to the Great Trigonometrical Survey under the guidance of George Everest. Waugh’s surveying expertise extended to numerous regions in central India, eventually leading him to the survey’s headquarters in Dehradun.

Notably, Everest observed that both Waugh and Renny possessed exceptional mathematical prowess and adeptness in handling surveying instruments, making them stand out as the best in these skills.

Discovery of the World’s Highest Peak: Waugh’s Himalayan Survey

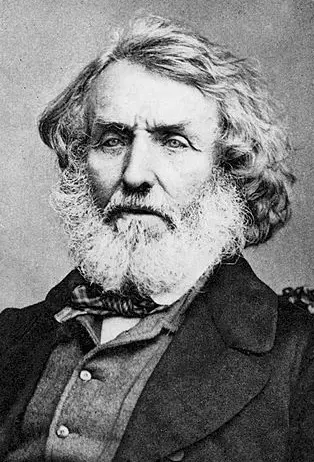

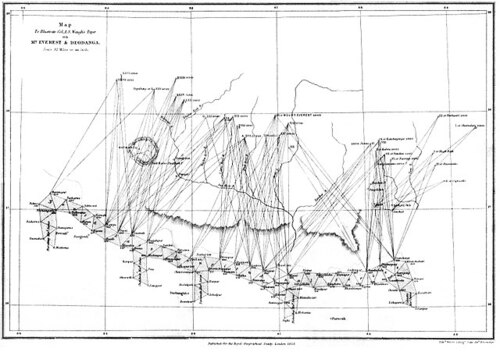

In 1843, after Sir George Everest’s retirement, he highly recommended Waugh as the most suitable candidate to assume the role of Surveyor General. Waugh embarked on surveying the challenging Himalayan region, covering an extensive distance of approximately 1690 miles from Sonakoda to Dehradun.

Navigating the Himalayas presented formidable obstacles due to their considerable height and unpredictable weather conditions, resulting in limited useful observations until 1847. The absence of electronic computers in that era meant that a team of human calculators had to invest several months in laborious calculations, analysis, and trigonometric extrapolation.

It was in 1852 that Radhanath Sikdar, the team’s lead human computer, approached Waugh with groundbreaking news. Sikdar revealed that what was previously marked as “Peak XV” had been identified as the highest point in the region and, quite possibly, the world. Thoroughly double-checking their calculations, Sikdar and Waugh ensured precision and accuracy before conveying the momentous discovery to the Royal Geographical Society. From their headquarters in Dehradun, they revealed that Kangchenjunga, not the previously thought peak, held the distinction of being the world’s highest peak.

Naming the World’s Highest Peak: The Proposal and Adoption of Mount Everest

With great caution and a meticulous approach, Waugh refrained from publishing the momentous result until the year 1856. During this period, he put forth the proposal to name the peak “Mount Everest” as a tribute to his predecessor, Sir George Everest. Initially, Waugh suggested “Mont Everest” but later made an amendment.

Sir George Everest had consistently used local names for the geographical features he surveyed, and Waugh diligently followed this practice. However, when dealing with Peak XV, now known as Mount Everest, Waugh faced a dilemma. The mountain had various local names, making it impossible to determine the most commonly used one. Hodgson, among others, argued that the native name for the peak was “Deodanga,” while another suggestion identified it as the mountain Hermann Schlagintweit had labeled as “Gaurisankar.”

Despite some objections from Everest himself, the name “Mount Everest” eventually received official recognition and adoption by the Royal Geographical Society several years after Waugh’s proposal.

Identifying Mount Everest: Andrew Scott Waugh’s Remarkable Find

The majestic height of Mount Everest was meticulously calculated to be precisely 29,000 feet (8,839.2 meters). However, when publicly declared, it was cleverly rounded up to 29,002 feet (8,839.8 meters) to avoid any misconception that the figure of 29,000 feet was a mere estimate. This witty maneuver has led to Waugh being humorously credited as “the first person to put two feet on top of Mount Everest.”

During his surveying, Waugh detected discrepancies in the triangulation, which he attributed to the gravitational attraction of the Himalayan mountains. To address this perplexing issue, he sought the expertise of Archdeacon John Henry Pratt, a mathematician and clergyman. Pratt delved into the matter and devised the concept of isostasy, shedding light on the phenomenon.

Following the groundbreaking identification of Mount Everest, Waugh received widespread acclaim. In 1857, the Royal Geographical Society honored him with its prestigious Patron’s Medal, and the subsequent year saw him become a Fellow of the Royal Society. In recognition of his achievements, Waugh attained the rank of Major General in 1861. Subsequently, Henry Thuillier replaced him as Surveyor General.

Waugh’s contributions extended beyond the fieldwork, as evidenced by his publication of “Instructions for Topographical Surveying” in 1861. Moreover, he disseminated the results of his surveys through numerous comprehensive reports, cementing his legacy as a distinguished surveyor and cartographer.

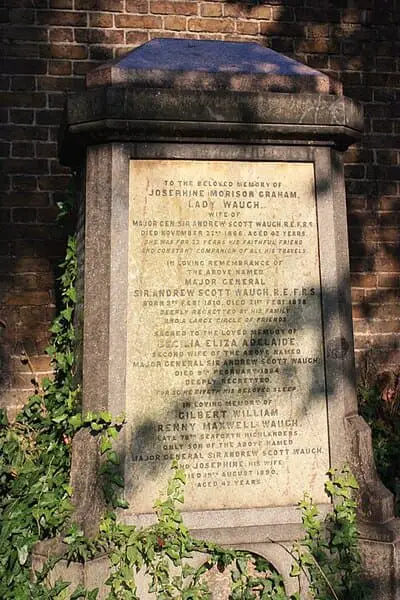

Waugh’s Burial in Brompton Cemetery

After his passing in 1878, Waugh found his final resting place in Brompton Cemetery, situated in west London. His burial site lies along the eastern wall, approximately midway within the cemetery.