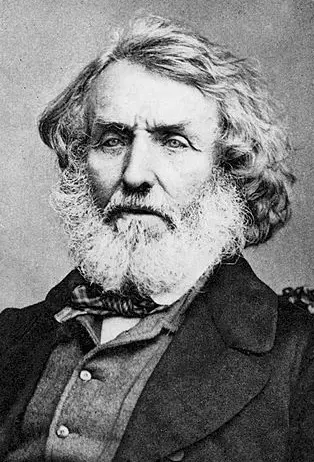

Sir George Everest, CB, FRS, FRAS, FRGS, born on 4th July 1790, was a distinguished British surveyor and geographer. His notable career included serving as the Surveyor General of India from 1830 to 1843.

Having received a military education in Marlow, Everest ventured to India at the age of 16, joining the East India Company. Throughout his journey, he became an assistant to William Lambton on the Great Trigonometric Survey. Later succeeded Lambton as the superintendent of the survey in 1823. One of his most significant accomplishments was leading the survey of the meridian arc stretching from the southernmost point of India to Nepal. It covered an impressive distance of approximately 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles).

In recognition of his exceptional contributions, Everest was appointed as the Surveyor General of India in 1830, a position he held until his retirement in 1843 when he returned to England.

The Renaming of Peak XV: Honoring Sir George Everest’s Legacy

In 1865, the Royal Geographical Society bestowed a great honor upon the recently identified highest peak, Peak XV. They decided to rename it Mount Everest in tribute to Sir George Everest, who had been a prominent British surveyor and geographer. Interestingly, it was Andrew Scott Waugh, Everest’s protege, and successor as surveyor general, who proposed the name in 1856.

The choice of Everest’s name came as a compromise due to the challenge of selecting from several local names for the mountain. Initially, Sir George Everest expressed reservations about accepting the honor, as he felt he had no direct involvement in the peak’s discovery.

Moreover, he believed that his name might prove difficult to write or pronounce in Hindi, the local language of the region. However, despite his initial objections, the mountain eventually came to be known as Mount Everest, forever immortalizing Sir George Everest’s name in the world’s geography.

Family Background of Sir George Everest

Sir George Everest’s birth date is recorded as 4th July 1790, but the exact location of his birth remains uncertain. The two potential birthplaces are either Greenwich or Gwernvale Manor, which belonged to his family and was situated near Crickhowell in Brecknockshire (now part of Powys), Wales. He was the eldest son among six siblings born to Lucetta Mary (née Smith) and William Tristram Everest. William Everest was a solicitor and justice of the peace, hailing from a well-established “Greenwich family” with a history that can be traced back to at least the late 1600s.

In terms of education, Everest attended the Royal Military College (Cadet Branch) in Marlow, Buckinghamshire. Then in 1806, he started his journey with the East India Company as a cadet. He received his commission as a second lieutenant in the Bengal Artillery and set sail for India in the same year.

Moreover, Everest was a Freemason, with his initiation occurring in Neptune Lodge, Penang (exact date unknown), under the authority of the United Grand Lodge of England. Following his return to England, he became a member of Prince of Wales’s Lodge in London on 20th February 1829.

George Everest: Surveying Triumphs and Health Challenges in India

Limited information exists regarding Everest’s early years in India, but it is evident that he possessed considerable proficiency in mathematics and astronomy. In 1814, he was assigned to Java, where Lieutenant-Governor Stamford Raffles entrusted him with the task of surveying the island. Returning to Bengal in 1816, Everest contributed significantly to expanding British knowledge of the Ganges and the Hooghly rivers. Subsequently, he undertook the survey of a semaphore line from Calcutta to Banaras (now Varanasi), covering an impressive distance of about 400 miles (640 km).

Colonel William Lambton, the leader of the Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS), recognized Everest’s work and appointed him as his chief assistant. Joining Lambton at Hyderabad in 1818, Everest actively participated in surveying a meridian arc extending northward from Cape Commorin. He shouldered much of the fieldwork responsibilities, but unfortunately, in 1820, he contracted malaria, which compelled him to recuperate at the Cape of Good Hope for a period.

Resuming his efforts in 1821, Everest assumed the role of superintendent of the GTS following Lambton’s passing in 1823. Over the ensuing years, he continued the progress of his predecessor’s work on the arc, advancing it up to Sironj, located in present-day Madhya Pradesh. However, Everest’s health suffered, and he endured the consequences of fever and rheumatism, which left him partially paralyzed. Consequently, he departed for England in 1825, spending the subsequent five years in a process of recovery.

In recognition of his contributions, Everest was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society in March 1827. During his leisure time, he dedicated himself to lobbying the East India Company for improved survey equipment and diligently studied the methodologies utilized by the Ordnance Survey. He frequently engaged in correspondence with Thomas Frederick Colby, sharing knowledge and ideas related to their surveying work.

The Great Trigonometrical Survey of the Indian Subcontinent

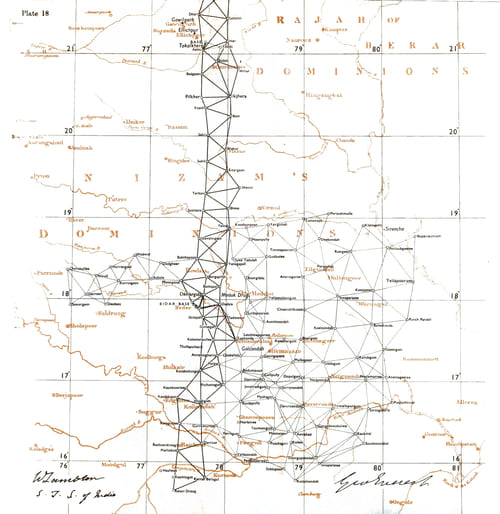

One of George Everest’s most significant achievements was the Great Trigonometrical Survey of the vast Indian subcontinent. This ambitious scientific endeavor aimed to conduct a comprehensive and detailed survey of the entire Indian landmass. Notably, the survey included the measurement of the heights of three towering Himalayan peaks: Everest, K2, and Kanchenjunga. Additionally, it marked a historic milestone by providing the first precise measurement of a segment of an arc of longitude, a remarkable accomplishment in the field of surveying.

The roots of this monumental undertaking can be traced back to 1806 when George Everest, alongside Colonel William Lambton, embarked on this momentous task. Even after Lambton’s passing in 1823, Everest continued to lead the project and tirelessly worked towards its completion. His dedication and expertise led to his appointment as the Surveyor-General of India, a position that granted him oversight over all geological and surveying missions throughout the vast expanse of India.

The goal of this project, initiated in 1802, was to achieve precise measurements across the entirety of the Indian subcontinent. George Everest was entrusted with the responsibility of continuing the measurement of a meridian arc stretching a staggering 2,400 kilometers from the southern tip of the peninsula to Nepal. In recognition of his exceptional commitment and leadership, he was appointed as the project superintendent after Lambton’s passing in 1823. Subsequently, in 1830, Everest was appointed as the Surveyor General of India, a position he held until his well-deserved retirement in 1843.

The Great Trigonometrical Survey, which had begun under Everest’s guidance, was ultimately completed in 1871 under the stewardship of James Walker, who succeeded Andrew Scott Waugh. This ambitious undertaking left a mark on the field of surveying and geography. Which forever etched George Everest’s name into history for his extraordinary contributions to science and exploration.

George Everest: Working as a Surveyor General of India

In June 1830, George Everest returned to India to resume his work on the Great Trigonometrical Survey (GTS) and, concurrently, he was appointed as the Surveyor General of India. After years of dedicated effort, the arc spanning from Cape Commorin to the northern border of British India was finally completed in 1841 under the watchful supervision of Andrew Scott Waugh.

However, Everest’s achievements were marred by a series of challenges. Much of his time was consumed by administrative tasks and addressing criticisms from his homeland. The East India Company had tentatively selected Thomas Jervis as Everest’s successor, and Jervis took this opportunity to deliver a series of lectures to the Royal Society, criticizing what he perceived as deficiencies in Everest’s methods.

Everest, in response, composed a series of open letters directed at Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex, who was the president of the Royal Society. In these letters, he vehemently condemned the society’s interference in matters they had little understanding of. The backlash prompted Jervis to withdraw from consideration, and Everest successfully advocated for his protégé, Andrew Scott Waugh, to be appointed as his successor.

Ultimately, in November 1842, George Everest decided to resign from his position, and in December 1843, his commission was officially revoked, marking the end of his tenure as the Surveyor General of India. Subsequently, he returned to England, concluding his remarkable and influential career in the field of surveying and geographical exploration.

A Pioneer’s Journey and Legacy

In 1845, George Everest embarked as a passenger on the inaugural voyage of the SS Great Britain. A groundbreaking event as it marked the world’s first ocean crossing by a steamship with a screw propulsion system.

Two years later, in 1847, Everest published a book titled “An Account of the Measurement of Two Sections of the Meridional Arc of India.” His exceptional contributions in this field earned him a prestigious medal from the Royal Astronomical Society. In recognition of his accomplishments, he was later elected as a fellow of both the Royal Asiatic Society and the Royal Geographical Society.

Throughout his career, Everest achieved notable ranks and honors. In 1854, he was promoted to the rank of colonel. Additionally, he received the distinguished title of Commander of the Order of the Bath in February 1861, followed by being knighted as a Knight Bachelor in March 1861.

George Everest’s remarkable journey came to an end on 1st December 1866 when he passed away at his residence in Hyde Park Gardens. He was laid to rest at St Andrew’s Church, Hove, located near Brighton, leaving behind a profound legacy as a pioneering surveyor and geographer.

George Everest’s Reluctance to Have His Name Associated with the Mountain

George Everest, although he had never laid eyes on the mountain that now bears his name, played a significant role in its discovery and recognition. As the Surveyor General of India, he made crucial decisions that influenced the exploration of the region. He hired Andrew Scott Waugh, who later made the first formal observations of the mountain, and Radhanath Sikdar, who calculated Everest’s height.

Before its true significance was realized, the mountain was known by different designations. Initially referred to as Peak “B,” it was later labeled as Peak XV. However, it was Waugh who brought the mountain to the world’s attention. In March 1856, he communicated with the Royal Geographical Society, asserting that the peak was likely the highest in the world. Given its lack of a known local name, Waugh proposed naming it “after my illustrious predecessor” – George Everest. He explained that due to the unavailability of access to Nepal, where native appellations might exist, the mountain’s original identity remained elusive.

Although there were native names among the Nepalese and Tibetans, these regions were off-limits to the British at that time. Consequently, people living farther south of the Himalayas had no specific name for the peak. This sparked a decade-long debate within the Royal Geographical Society and other scholarly institutions. Various scholars proposed alternative native names for the mountain, such as “Deva-dhunga” by Brian Houghton Hodgson and “Gaurisankar” by Hermann Schlagintweit.

George Everest himself expressed reservations about having his name used for the mountain, citing concerns that the native people of India would struggle to pronounce it and that it was not easily written in Hindi. Nevertheless, in 1865, the Royal Geographical Society officially settled on the name “Mount Everest” as the lasting tribute to the extraordinary surveyor, despite his objections. This decision marked the beginning of the mountain’s enduring association with George Everest’s name, even though he never set eyes on the majestic peak.

Unveiling the Original Local Names for Mount Everest

In the early 20th century, the esteemed Swedish explorer Sven Hedin made a remarkable discovery, uncovering the long-forgotten Tibetan name for Mount Everest – Cha-mo-lung-ma. Interestingly, this name had already been documented on a map created by the geographer D’Anville in Paris as early as 1733.

Thus, Chomolungma, also sometimes written as Qomolangma, holds the distinction of being the authentic and traditional Tibetan name for Mount Everest, signifying “Goddess Mother of the World.”

In Nepal, Mount Everest is known as Sagarmatha, which translates to “Goddess of the Sky.” It is worth noting that some individuals use the name Mount Everest exclusively for the tallest peak, while referring to the entire massif of peaks, including Everest, Nuptse, and Lhotse, as Qomolangma. Despite these traditional designations, the term “Mount Everest” remains the most widely recognized name across the globe.

Sir George Everest’s House and Laboratory

For approximately 11 years, George Everest owned a house in Mussoorie, Uttarakhand, India. Interestingly, he purchased the property, known today as Sir George Everest’s House and Laboratory or Park House. Although now mostly dilapidated, the house retains its roof, and there have been various proposals to transform it into a museum.

The house, originally constructed in 1832, is nestled within Park Estate, approximately 6 kilometers (4 miles) west of Gandhi Chowk / Library Bazaar, which marks the west end of Mall Road in Mussoorie. Its location affords breathtaking panoramic views of the Doon Valley on one side and the Aglar River valley and the majestic Himalayan Range to the north.

Presently, the house falls under the jurisdiction of the Tourism Department. Outside the property, there are underground water cisterns, or possibly pits used for storing ice due to the area’s scarcity of water. Unfortunately, these pits lie uncovered in the front yard, filled with litter, posing a safety hazard.

While the interior has been stripped of its furnishings, the fireplaces, roof, door, and window frames still stand. The house remains secured by steel grills, restricting entry. Over time, the property has gained more attention, and the access road has been improved, leading to the walls being covered with graffiti and periodically whitewashed clean.

In recent years, new fencing, tree planting, and the construction of a ticket booth indicate that there might be an entry fee in the future. Conservation architects at the Indian National Trust are vying for the opportunity to undertake the restoration project.

As of 2023, the house and its surroundings have undergone significant improvements. However, the house and laboratory are not yet open to the public. Visitors can enjoy the serene surroundings and small cafes serving limited menus that have sprung up around the property.