Maurice Wilson, an enigmatic figure from the early 20th century, captivated the world with his audacious ambitions and unwavering determination. Born in 1898 in England, Wilson’s life was a remarkable tale of adventure, becoming known for his ill-fated attempt to crash land a plane on Mount Everest and summit it in 1934.

Without any prior mountaineering or flight experience, Maurice Wilson set out for Everest from England in 1933. Despite his unconventional methods and against all odds, Wilson’s courageous spirit and extraordinary quest for personal achievement got him all the way to the north side of Everest.

But what happened to the pilot after reaching Everest? This blog will answer that question and provide information about the life of Maurice Wilson.

Maurice Wilson’s Early life and Service in World War I:

Born in Bradford, West Yorkshire, Maurice Wilson’s life took an unexpected turn with the onset of the First World War. Originally destined to follow in his father’s footsteps and work in the family’s woolen mill, Wilson instead enlisted in the British Army on his eighteenth birthday. His exceptional bravery and leadership skills quickly propelled him up the ranks, ultimately achieving the rank of Captain.

Serving in France from November 1917 during WWI, Wilson’s courage earned him the esteemed Military Cross in April 1918. During a fierce engagement near Wytschaete, he defended a machine gun post against advancing German forces, despite being the sole uninjured survivor of his unit. His reward citation read as followed:

“2nd Lt. Maurice Wilson, W. York. R. For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He held a post in advance of the line under very heavy shell and machine-gun fire on both flanks after the machine guns covering his flanks had been withdrawn. It was largely owing to his pluck and determination in holding this post that the enemy attack was held up.”

Maurice Wilson’s Award Citation

His unwavering resolve played a pivotal role in halting the enemy’s attack. Tragically, Wilson suffered severe injuries from machine gun fire near Ypres months later. The event and injuries sustained plagued him for the rest of his days – with his left arm bearing the scars of his sacrifice.

The image above is of Maurice Wilson during WWI.

Wilson’s Illness and recovery after WWI:

After departing from the army in 1919, Maurice Wilson, had difficulties adjusting to civilian life. Engulfed in a sense of aimlessness, he embarked on a wandering journey, residing in London, the United States, and New Zealand, while taking on various occupations. Despite eventual financial success, Wilson found no solace or contentment. His physical and mental health deteriorated, marked by weight loss and persistent bouts of coughing.

During 1922, Maurice Wilson entered into a marriage with Beatrice Hardy Slater. As per records, he worked as a merchant, likely employed in his late father’s mill. The details surrounding the conclusion of this marriage remain elusive, including when and how it ended, and no children are known to have resulted from the union. Subsequently, in 1926, Wilson entered into another marriage, this time with Ruby Russell, during his time in New Zealand. However, it is widely believed that his heart truly belonged to Enid Evans, the wife of Len Evans, resulting in a complex and intricate love triangle between the three individuals.

A turning point arrived in 1932 when Wilson underwent treatment that entailed an intensive period of thirty-five days characterized by fervent prayer and complete fasting. He attributed this method to a mysterious figure he had encountered in Mayfair, who allegedly possessed the ability to cure himself and countless others of supposedly incurable diseases.

Curiously, Wilson never disclosed the identity of this individual, leaving doubts as to whether such a person truly existed or if the treatment was a product of Wilson’s own combination of Christian and Eastern mystical beliefs. Regardless of its origins, Wilson’s unwavering conviction in the potency of prayer and fasting became unwavering, leading him to embrace the role of a fervent advocate, dedicating his life to spreading awareness about their transformative powers.

Maurice Wilson Getting Ready to fly to Mount Everest:

Maurice Wilson conceived the audacious idea of conquering Mount Everest while in Germany’s Black Forest. Inspired by news articles detailing the 1924 British Mount Everest expedition and the upcoming 1933 Houston Everest Flight, he became convinced that his unwavering faith in God and the power of fasting would lead him to succeed where renowned climbers George Mallory and Andrew ‘Sandy’ Irvine had tragically failed.

Undeterred by his lack of experience in aviation or mountaineering, Wilson devised a plan. He intended to fly a small aircraft to Tibet, crash-land it on Everest’s upper slopes, and then trek to the summit. Such a feat would have posed a formidable challenge even for the most accomplished aviators and mountaineers of the era.

Notably, solo ascents of Everest were not achieved until many decades later, in 1980. Wilson acknowledged his knowledge gaps and set out to acquire the necessary skills.

Acquiring a three-year-old de Havilland DH.60 Moth, named ‘Ever Wrest’. Wilson embarked on a journey to learn how to fly, however he was a lackluster student, taking double the average time to obtain his pilot’s license. Undeterred by skepticism, Wilson obtained his license, proclaiming to his instructor that he would either reach Everest or perish in the attempt.

Unfortunately, Wilson’s preparations for the upcoming trip to Tibet were as woeful as his training. He neglected to procure specialized equipment or acquire essential technical mountaineering skills. Instead, he spent a mere five weeks wandering the hills of Snowdonia and the Lake District before deeming himself ready.

Criticism on Maurice’s Poor Planning and Preparation for Everest:

Scholars have suggested that Wilson’s naivety may have been influenced by the style of reports on the early British expeditions on Everest. Reflecting the prevailing Victorian restraint, mountaineering literature of the time often downplayed the dangers and difficulties faced by climbers, dismissing treacherous slopes, steep ice walls, and sheer rock faces as mere “bothers.”

Additionally, the debilitating effects of high altitude were poorly understood and received minimal emphasis. However, it remains astonishing that Wilson did not undertake basic training on snow climbing, as a single glance at a photograph of the mountain would have revealed its necessity.

Maurice Flying to India:

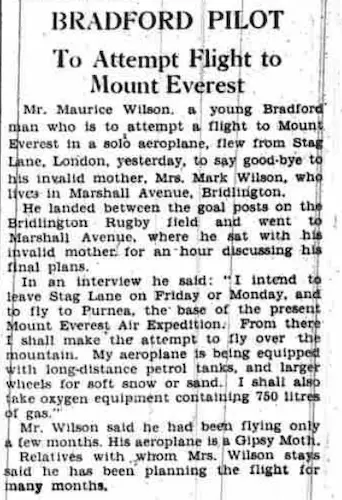

Wilson initially planned to depart for Tibet in April 1933, but his journey encountered a setback when he crashed his plane in a field near Bradford. Miraculously, he emerged unscathed from the accident, but the resulting damage to the aircraft necessitated a three-week repair period. The crash not only intensified the media spotlight on Wilson but also caught the attention of the Air Ministry, which issued a prohibition on his flight.

Undeterred by the Air Ministry’s ban, Wilson set off on May 21, against the efforts of the British government. He managed to reach India two weeks later, despite numerous obstacles. However, his plans faced further obstacles when, upon his arrival in Cairo, his authorization to fly over Persia was suddenly revoked. Undeterred, Wilson redirected his flight to Bahrain, only to be denied permission to refuel due to the British consulate’s orders. They argued that since all suitable airstrips within his aircraft’s range were in Persia, he would not be allowed to proceed.

Under the condition of retracing his route and returning to Britain, Wilson was eventually permitted to refuel. However, once airborne, he defied the agreement and changed his course towards India.

Although the airstrip at Gwadar, the westernmost location in India, exceeded his aircraft’s range, Wilson managed to land after nine hours of flight, with his fuel gauge reading zero. Safely in India, he pressed on with his journey across the country. However, his ambitious flight came to an abrupt halt in Lalbalu when authorities reiterated their refusal to allow him to fly over Nepal, impounding his plane to prevent any further attempts.

Maurice Wilson – Moving from India to Tibet:

After facing disappointment in his attempts to gain permission to enter Tibet by foot, Wilson spent the winter in Darjeeling, immersing himself in fasting and preparations for an unauthorized journey to the base of Mount Everest.

He encountered three Sherpas—Tewang, Rinzing, and Tsering—who had previously served as porters on the 1933 Everest expedition led by Hugh Ruttledge. These Sherpas agreed to accompany Wilson on his daring endeavor.

On March 21, 1934, Wilson and his three sherpas discreetly departed from Darjeeling, disguising themselves as Buddhist monks. Wilson pretended to be deaf, mute, and sick to evade suspicion while crossing into Tibet. Finally, on April 14, they arrived at the Rongbuk Monastery, where they were warmly welcomed, and Wilson gained access to the equipment left behind by Ruttledge’s expedition. After a mere two days, he embarked alone towards Mount Everest, leaving the monastery behind.

Maurice Wilson on Mount Everest – His Attempt to Summit:

The primary source of information about Wilson’s activities on the mountain stems from his recovered diary, currently held in the archives of the Alpine Club. With no prior experience in glacier travel, Wilson encountered immense challenges during his ascent of the Rongbuk Glacier. Frequently losing his way, he had to retrace his steps repeatedly. A clear demonstration of his inexperience surfaced when he stumbled upon a pair of crampons at an old 1933 expedition camp, and then discarded them.

After five days of battling weather conditions, Wilson found himself two miles away from Ruttledge’s Camp III below the North Col. Expressing his disappointment in his diary, he wrote, “It’s the weather that’s beaten me – what damned bad luck.” Exhausted and facing deteriorating conditions, he embarked on a grueling four-day retreat down the glacier. Upon his return to the monastery, he was physically drained, suffering from snow blindness, and a badly twisted ankle.

Despite an eighteen-day recovery period, Wilson ventured forth once again on May 12, accompanied by Tewand and Rinzing. With the Sherpas’ expertise in navigating the glacier, they made progress and reached Camp III near the base of the slopes below the North Col in a mere three days. Adverse weather conditions confined them to camp for several days, during which Wilson contemplated potential routes to ascend the mountain. An entry in his diary raised concerns about his lack of understanding, when he was hopeful that the steps carved into the ice and ropes from the previous year might still exist.

On the 21st, Wilson made a fruitless attempt to reach the North Col, only to discover the absence of the rope and steps he had anticipated. Undeterred, the following day he embarked on another endeavor to reach the Col. After four days of slow progress and camping on exposed ledges, he was ultimately defeated by a forty-foot ice wall at approximately 22,700 feet, a formidable challenge that had tested experienced climber Frank Smythe in 1933.

Although the Sherpas implored Wilson to abandon his pursuit and return to the monastery, he refused. Speculation surrounds his motivations—whether he still believed in the possibility of conquering the mountain or whether he embraced his fate, preferring death over the shame of an unsuccessful return to Britain.

In his diary, Wilson wrote, “This will be a last effort, and I feel successful,” before setting off alone for the final time on May 29. Weakened and unable to attempt the Col that day, he established camp at its base, a mere few hundred yards from where the Sherpas were encamped. The subsequent day, he remained in bed. His final diary entry, dated May 31, was brief yet poignant: “Off again, gorgeous day.”

As Wilson failed to return from his last endeavor, Tewand and Rinzing departed from the mountain. They arrived in Kalimpong in late July, they told the world of what happened to Maurice Wilson on Everest.

Was Maurice Wilson’s body found on Everest?

During a reconnaissance expedition to Everest in 1935, led by Eric Shipton, the body of Maurice Wilson was found at the base of the North Col. The corpse lay on its side in the snow, accompanied by the remnants of a tattered tent, and a rucksack containing Wilson’s diary and camera film was discovered in close proximity.

As a final resting place, the team chose to inter his body in a nearby crevasse. It is widely believed that Wilson succumbed to exhaustion or starvation. However, the precise date of his passing remains unknown.

There is an interesting account of the reconnaissance expedition team that found Maurice’s body on Everest recorded in their official report submitted in Darjeeling. The report contains information about their discovery, letters sent to his wife, and the overall events of what happened. You can see the documents of the ‘Report regarding the discovery of the body of Maurice Wilson above Camp III on Mount Everest’, held by the National Archives of India.

Image is of Maurice Wilson’s body in 1935 when Eric Shipton found him.

The Controversy of Maurice’s Everest Summit:

In 2003, Thomas Noy put forth a proposition suggesting that Maurice Wilson might have successfully reached the summit of Everest but perished during his descent. Noy’s theory draws support from an interview he conducted with Tibetan climber Gombu, a member of the Chinese expedition in 1960.

Gombu recalled encountering the remnants of an old tent at an altitude of 8,500 meters. If accurate, this would surpass the highest camps established by previous British expeditions, implying that Wilson had ascended to a significantly greater height than previously presumed. However, Noy’s theory has not garnered widespread acceptance within the mountaineering community.

Doubts persist regarding the plausibility of an inexperienced amateur like Wilson accomplishing an unassisted climb of the mountain. Prominent climber Chris Bonington has expressed unequivocal skepticism, asserting that Wilson would have had no chance of success. Climbing historian Jochen Hemmleb and Wilson’s biographer, Peter Meier-Hüsing, have questioned the accuracy of Gombu’s account, highlighting that it contradicts the recollections of other members from the 1960 expedition.

Additionally, some have speculated that if the tent at 8,500 meters did exist, it could have been a remnant from the rumored Soviet expedition of 1952. However, the existence of the Soviet expedition itself remains uncertain.

Books about Wilson’s Everest Attempt:

Numerous books have delved into the details of Wilson’s expedition, capturing the intrigue surrounding his quest for Everest. One notable publication is Dennis Roberts’ 1957 book titled “I’ll Climb Everest Alone,” which was later reprinted in paperback by Faber in 2011.

Wilson’s endeavor was also referenced in Tony Astill’s work, “Mount Everest The Reconnaissance 1935,” as well as Walt Unsworth’s comprehensive book simply titled “Everest.” In 2020, Ed Caesar shed light on Wilson’s extraordinary tale in “The Moth and The Mountain: A True Story of Love, War, and Everest.” (Affiliate link!)

These publications offer different perspectives on Wilson’s journey, chronicling his passion, determination, and the challenges he faced in his pursuit of conquering Mount Everest alone.

The Pilot who tried to Crash Land on Mount Everest – Maurice Wilson:

Maurice Wilson’s extraordinary attempt to crash-land a plane on Everest and subsequently summit the peak stands as a testament to his determination to prove something to the rest of the world. Despite his lack of experience in both aviation and mountaineering, Wilson embarked on a daring adventure driven by his fervent belief in the power of prayer and fasting.

While his expedition ultimately ended in tragedy, with him dying on Everest in 1934, Wilson’s spirit and pursuit of his goal captivates the imagination of people while raising countless questions on his decision to try and become the first person to summit Everest.

FAQs: Maurice Wilson Mount Everest

Below are the most frequently asked questions regarding Wilson’s attempt to crash land on Everest and summit the mountain in 1934.

Although he had no prior experience in mountaineering or flying, he managed to accomplish the remarkable feat of flying from Britain to India, covertly entering Tibet, and ascending as high as 6,920 meters (22,703 ft) on Mount Everest. Unfortunately, Wilson met his demise during his courageous endeavor, and his lifeless remains were discovered the subsequent year by a British expedition.

In “The Moth and the Mountain,” penned by acclaimed New Yorker writer Ed Caesar, unfolds an epic tale of a solitary individual’s quest to heal the scars of war and find redemption by embarking on a daring escapade: piloting his biplane on an audacious five-thousand-mile journey across the globe and endeavoring to achieve an unprecedented feat of scaling the summit of Mount Everest, thus etching his name in history as the first person to conquer the majestic peak.