The 1921 British Reconnaissance expedition was carried out in order to find a way up the mountain and be the first people to reach its summit. During that time, foreigners weren’t allowed in Nepal, so their expedition to Everest had to approach from Tibet in the north. They found a way by going up the Kharta Glacier from the east and then crossing the Lhakpa La to the North East of Everest. After that, they had to go down to the East Rongbuk Glacier and then climb again to reach Everest’s North Col. However, even though they reached the North Col, they couldn’t go higher and had to stop the expedition.

At first, they explored from the north and found the Rongbuk Glacier. They didn’t see any feasible route to the top of the mountain from there. However, they also didn’t realize at the time that the East Rongbuk glacier actually joined the Rongbuk glacier. They thought it went away to the east. The 1921 reconnaissance expedition succeeded in its initial exploration by discovering a viable route that could be followed. They realized that it might work best to go to the East Rongbuk glacier through the Rongbuk glacier, and then follow the path to the summit that goes by the North Col.

Charles Howard-Bury was the leader of the 1921 expedition. George Mallory, who hadn’t been to the Himalayas before, was part of the team. Interestingly, Mallory ended up being the main climber during the expedition. In the following year, the 1922 British Mount Everest expedition used this route. They managed to climb above the North Col, which was the highest point any person had ever reached till then. However, they were unsuccessful in reaching the the summit.

Early Steps Towards Exploring Mount Everest

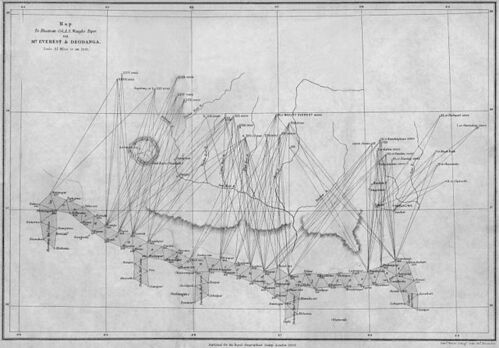

In 1856, during the Great Trigonometric Survey, it was determined that the tallest peak in the world wasn’t Kangchenjunga as previously thought, but rather a less recognized mountain called Peak XV. This mountain was measured to be 29,002 feet high. In 1907, marking the 50th anniversary of the Alpine Club, a plan was established for a British exploration of Everest.

General Charles Bruce, who later became the club’s president, was selected to lead this expedition. The challenge of gaining access to Tibet, a region historically closed to outsiders, started to change due to the efforts of Sir Francis Younghusband. Despite initial hesitations due to political concerns, approval was finally granted for the expedition in 1920 by the Secretary of State for India.

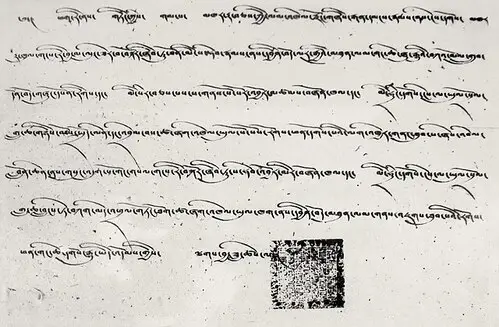

Colonel Charles Howard-Bury, as part of a diplomatic mission, successfully persuaded Lord Reading, the Viceroy of India, to support the expedition. Since Nepal was inaccessible at that time, the intended approach for the expedition would be through Sikkim. Sir Charles Bell, the viceroy’s representative in Sikkim, had established positive relations with the Dalai Lama during his work in Lhasa. As a result, the Dalai Lama granted permission for the expedition to pass through, issuing an entry pass for the journey.

In January of 1921, the collaboration between the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society, led to the establishment of the Mount Everest Committee. This committee was formed with the aim of coordinating and financing the upcoming expedition. While there was initial enthusiasm for a full-scale attempt to reach the summit of Mount Everest, over time, the committee members reached a consensus that the primary objective of the mission should be reconnaissance and exploration rather than an all-out summit push.

The 1921 Expedition Team

Due to Bruce’s military commitments, he was unable to join the expedition, resulting in Howard-Bury being selected as the leader. The primary objective of this expedition was reconnaissance. At the time, the closest any explorer had come to the mountain was around 60 miles (97 km). In April 1921, the expedition commenced. The climbing team comprised experienced mountaineers Harold Raeburn and Alexander Kellas, along with two less experienced individuals, George Mallory and Guy Bullock, both alumni of Old Wykehamists with no prior Himalayan experience.

The team also included Sandy Wollaston, a naturalist and doctor, Alexander Heron, a geologist, Henry Morshead (also an Old Wykehamist), and Oliver Wheeler, surveyors from the army. The expedition organized Sherpas, Bhutias, porters, supplies, and a hundred Army mules (later replaced with hill mules and yaks). Their journey commenced on May 18, 1921, departing from Darjeeling in British India, for a 300-mile (480 km) march towards Everest. Throughout their trek, the climate transitioned from hot and humid with lush vegetation and frequent heavy rainfall to cold, dry, and exceedingly windy conditions.

Their route led them through Sikkim, heading northeast through the Tista valley, over the Jelep La pass into Tibet, and into the Chumbi Valley. They passed through Phari at an altitude of 4,400 meters (14,300 feet), crossed the Himalayan watershed at Tang La, and continued onto the Tibetan plateau. Turning away from the Lhasa road and adopting a westward course, the expedition reached Khamba Dzong.

Tragedy struck on June 6 when Kellas passed away suddenly due to heart failure. Subsequently, Raeburn fell ill and had to return to Sikkim. The team continued their journey along the Arun River valley to the west. Upon reaching Shiling, they finally had a clear enough view of Everest to begin assessing its topography. Progressing through Shekar Dzong, they arrived at Tingri Dzong, which served as the base for the northern phase of their explorations.

The Northern Reconnaissance Expedition:

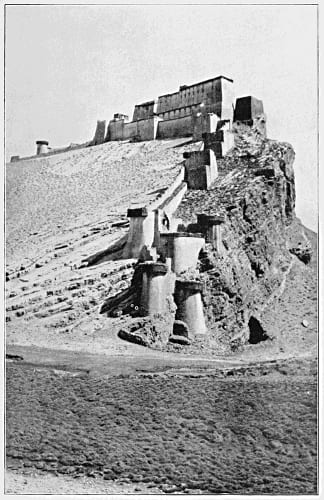

Starting from Tingri, a number of valleys opened up, stretching southward towards Everest. On June 23, Mallory and Bullock embarked on a journey to the south along with sixteen Sherpas and porters. After two days, they reached Chobuk and found themselves at the base of the Rongbuk valley, from where the sight of Everest became visible. Progressing another ten miles, they arrived at the snout of the Rongbuk Glacier. It was at this point, at an elevation of 5,000 meters (16,500 feet), that they established their base camp. This location was just beyond the Rongbuk Monastery, which Mallory referred to as “Chöyling”.

Their experience up to this point had been primarily with Alpine glaciers, and they faced challenges dealing with 15-meter (50-foot) tall seracs. Their struggles led them to retrace their steps back to an altitude of 5,600 meters (18,500 feet), near where the West Rongbuk Glacier emerges.

Rongbuk Glacier:

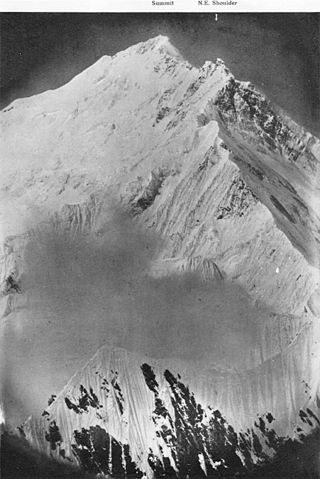

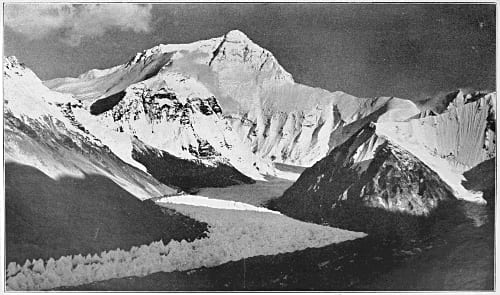

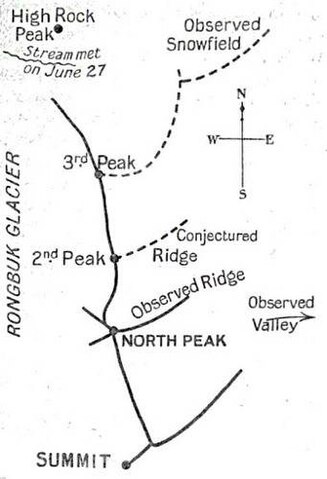

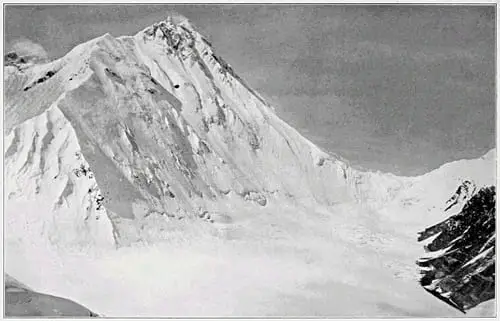

After dedicating six days to acclimatization and recovery, the team set up Camp II at an elevation of 5,300 meters (17,500 feet). On July 1st, Mallory, accompanied by five Sherpas, embarked towards the glacier’s upper region, situated close to Everest’s North Face. They ascended to a height of 5,800 meters (19,100 feet), allowing Mallory to conduct an assessment of the western side of the North Col.

During this evaluation, it became apparent that finding a satisfactory route to the North Col itself was challenging. However, higher up the mountain, in the direction of the summit, a viable path seemed feasible. Conversely, the view from this vantage point did not present a promising perspective of Everest’s west ridge. In light of these observations, Mallory concluded that exploring the West Rongbuk glacier would be the next logical step.

West Rongbuk Glacier:

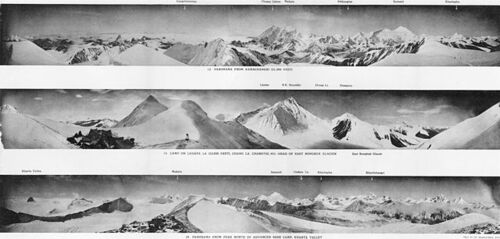

On July 5th, Mallory and Bullock decided to scale the 6,900-meter (22,500-foot) Ri Ring peak to gain a clearer understanding of the intricate topography to the west. Their aim was to gain a more advantageous perspective on the terrain. This vantage point allowed them to closely inspect the upper North Face of Everest as well as the north ridge situated above the North Col. From their observations, they concluded that the north ridge appeared to be manageable.

However, during their assessment, they made a misjudgment about the geographical layout. They wrongly thought a prominent ridge extended from Everest’s North Peak to the Arun river. This misperception led them to believe an approach to the eastern side of the North Col wasn’t feasible from Rongbuk. They failed to anticipate that the glacier on the opposite side of the North Col would eventually reconnect with the main Rongbuk glacier. In reality, only a small stream is visible where the glaciers meet, just above the Rongbuk Monastery.

Upon further examination towards the western direction, they identified two potentially promising climbing routes to Everest. One involved crossing the Lho La, situated at the upper end of the Rongbuk glacier, while the other option was traversing an unnamed col located between Pumori and Lingtren peaks. The hope was that a valley south of these cols could potentially offer a viable route to the summit. Mallory scaled a peak he referred to as “Island Peak” (now known as Lingtrennup), from which he attempted to capture photographs of Changtse, Everest, and Lhotse.

Through further exploration, they eventually reached the unnamed col by ascending the Pumori Glacier in a western direction. By July 19th, they were able to peer down into the Western Cwm and the Khumbu Glacier. While they couldn’t spot the South Col, they regarded the Khumbu glacier as “terribly steep and broken.” Furthermore, the steep 460-meter (1,500-foot) descent from their col to the glacier posed an insurmountable challenge. Consequently, any approach through the Western Cwm would require an expedition from Nepal, following a different route.

Photographic Challenges and Unforeseen Setbacks:

On July 20th, the decision was made to dismantle the camps, although a specific route had not yet been determined. The potential of accessing the North Col from the eastern direction remained under consideration. Prior to heading in that direction, Mallory and Bullock initiated an exploration of an area that, unbeknownst to them, marked the point where the East Rongbuk glacier flowed out. Their intent was to investigate this area.

However, their progress was hindered by unfortunate news: the photographs Mallory had taken turned out to be unusable due to the incorrect placement of photographic plates. Given the essential role of photographs in the reconnaissance efforts, Mallory and Bullock dedicated two days to swiftly retaking as many photographs as possible.

During this period, Mallory retook photographs from his vantage point on “Island Peak,” while Bullock successfully reached the Lho La, capturing photographs of the Khumbu Icefall. By July 25th, they reunited with Howard-Bury’s team at Chobuk, bringing this phase of their expedition to a close.

The Eastern Reconnaissance Expedition: Kharta and the Kama Valley

Fueled by a belief that the river at Kharta originated from the North Col of Everest, Mallory and Bullock walked upstream on August 2nd. Their initial suspicions were challenged the following day when local residents informed them that a distinct river flowed from Everest. This revelation prompted them to cross a high pass at 5,500 meters (18,000 feet). This led them into the valley of the Kama River, running parallel but to the south of their previous route. Here, they found themselves in close proximity to Makalu, which lay further to the south.

As they advanced westward, Lhotse and Everest came into view, with the Kangshung Glacier and Kangshung Face drawing nearer. Enveloped by the towering presence of three of the world’s highest peaks, Mallory eloquently characterized the Kama valley as “magnificent and sublime.” He added that its beauty could be further enhanced with an additional touch of tenderness. While the Kangshung Face’s challenge is insurmountable, Mallory firmly asserts it’s not their path to take.

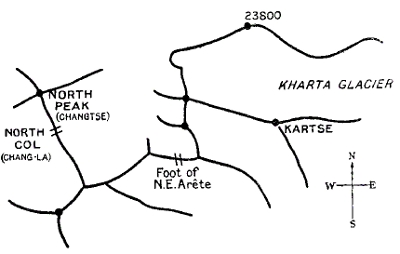

Realizing that their return path lay through the Kharta valley, they charted a course back. To facilitate their planned return, Mallory and Bullock successfully ascended the 6,520-meter (21,390-foot) Kartse peak on August 7th. This ascent allowed them to examine the North Col and the Kangshung Face in greater detail. They pondered whether the northern valley’s glacier connected to the North Col or lay farther north. The intricacies of Everest’s northeast ridge were evaluated and deemed challenging. With options narrowing, the North Col and the north ridge above it remained the sole possibilities.

Following their comprehensive survey, they descended Kartse and returned to Kama before ultimately retracing their steps back to the Kharta valley. This marked yet another chapter in their extensive exploration of Everest’s intricate surroundings.

Return to Kharta valley

Amidst their undertaking, Mallory’s health faltered, compelling Bullock to continue westward towards the head of the Kharta glacier on August 13th. However, a swift return from a messenger soon informed Mallory that Bullock had observed the glacier terminating at a higher pass ahead. This discovery suggested that the glacier stemming from the North Col might not extend in the eastern direction as initially speculated.

As Bullock retraced his steps, news arrived in the form of a letter from Wheeler, presenting the outcomes of his survey. The letter detailed that the glacier descending from the east side of the North Col veered sharply northward, ultimately converging with the primary Rongbuk Glacier.

Given the constraints of time, a returning back to Rongbuk was impractical. With the revised understanding, the Rongbuk Glacier was likely the most viable approach to the North Col. The team resolved to explore the route to the pass Bullock had identified. This pass, dubbed Lhakpa La or “Windy Gap,” warranted further investigation to ascertain whether it could provide access to the North Col.

Despite challenging weather conditions and the glacier terrain, they reached the 6,800-meter (22,200-foot) Lhakpa La on August 18th. Mallory concluded that the route was indeed feasible, marking a significant achievement. With this determination, the decision was made to conclude the reconnaissance phase.

Progress of the 1921 Expedition: Climbing the North Col

While Mallory and Bullock took a period of rest, the expedition established an advance base camp at an elevation of 5,300 meters (17,300 feet) and camp II at 6,100 meters (20,000 feet) on the Kharta glacier. These camps were strategically placed, with the intention of facilitating the upcoming stages of the expedition. Remarkably, both these camps were set up and organized, despite being left unoccupied at the time.

The blueprint for the subsequent stages of the expedition was laid out. The plan included the establishment of camp III at the Lhakpa La, camp IV at the North Col, and an additional camp before reaching the summit. However, in hindsight, this plan gravely underestimated the challenges that awaited them on the mountain.

The progression of their efforts was influenced by the monsoon season, necessitating a month-long wait for its conclusion. As the monsoon abated, the team cautiously transitioned to the advanced base camp on August 31st. Notably, Raeburn, who had unexpectedly returned, was able to rejoin the team at this juncture. This pivotal step marked the renewed momentum of the expedition after the monsoon’s hiatus.

Triumphs and Trials: Ascending the North Col

The team’s stay at the advanced base camp extended until September 20th, awaiting improved weather on Everest. Subsequently, on this day, Mallory, Bullock, Morshead, and Wheeler embarked on the journey to Lhakpa La, successfully reaching their destination. Acknowledging the need for an interim camp at the North Col, they returned to camp II for more supplies. Armed with the necessary provisions, the entire team, excluding Raeburn, joined by twenty-six Sherpas, set out for camp III.

Next day, Mallory, Bullock, Wheeler, and three Sherpas descended to the East Rongbuk glacier, while the rest turned back. The night that followed on the glacier proved arduous, marked by cold and windy conditions. However, on September 24th, the party reached the North Col, although without carrying heavy loads. The terrain of the Col offered a suitable spot for setting up a camp, but the relentless wind conditions made progress impossible. In light of these challenges, they descended to the glacier.

After thorough consideration, Mallory and Bullock determined a camp at 7,000 meters (23,000 feet) on the North Col wasn’t feasible. The severity of the wind, coupled with the increasingly fierce gales, further discouraged their efforts. Forced by circumstances, the team climbed back to the Lhakpa La on September 25th.

As their options dwindled, the expedition made the decision to abandon the upper camps on September 26th. Their journey ended at Kharta, ultimately reaching Darjeeling by October 25th, concluding the expedition without any major setbacks.

For his leadership of the expedition, Howard-Bury was recognized and awarded the 1922 Founder’s Medal by the Royal Geographical Society. This acknowledgment reflected his instrumental role in overseeing the expedition’s efforts.

Shaping the Path Forward: Reflections and Plans after the 1921 Expedition

Before the conclusion of the 1921 expedition in Tibet, the Mount Everest Committee convened to formulate their next steps. The decision was reached to launch a comprehensive endeavor in 1922, led by General Bruce. The proposed route would include Rongbuk, East Rongbuk, and the North Col. Oxygen cylinders would be added for the climbers, aiming to enhance their chances of success.

The 1921 expedition garnered acclaim not only from experts but also from the broader public. The warm reception included an official welcome-home event hosted by the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club at London’s Queen’s Hall.

In discussing the impending summit attempt during his address at the Queen’s Hall, Mallory expressed a tempered outlook. He acknowledged the formidable challenges ahead, expressing doubt about the prospects of success. He stressed the dangers of exhausted climbers reaching the summit, highlighting the endeavor’s sobering reality.

Mallory’s aspirations extended beyond the expedition. He had envisioned a transition from his role as a schoolteacher to that of a mountaineer and writer. His contributions to Howard-Bury’s book, which chronicled the 1922 expedition, were contingent on payment. Yet by 1923, as preparations for the 1924 Everest expedition loomed, Mallory had not received the agreed-upon compensation. Disappointingly, the Committee reversed their earlier commitment to payment, although they acknowledged the value of his contributions.

Tragically, the 1924 expedition would be Mallory’s last. His remains were eventually identified in 1999. The expedition’s legacy continued with Bullock’s 1962 diary publication, offering insights into pioneering mountaineering.