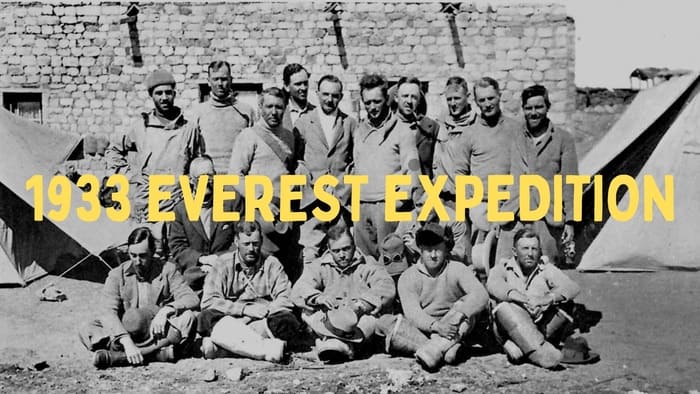

The 1933 British Mount Everest expedition marked the fourth British endeavor to conquer Mount Everest. It followed the preliminary 1921 reconnaissance expedition, along with the more extensive attempts in 1922 and 1924 expedition.

Despite the earlier efforts to reach the peak, the 1933 Mount Everest expedition was also unable to achieve its goal. Notably, two distinct efforts were carried out during the expedition. Lawrence Wager and Percy Wyn-Harris, and F. S. Smythe, established a new altitude record for climbing without the use of supplemental oxygen. This record was held until Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler effectively reached the summit of Mount Everest in 1978.

Background of The 1933 Everest Expedition

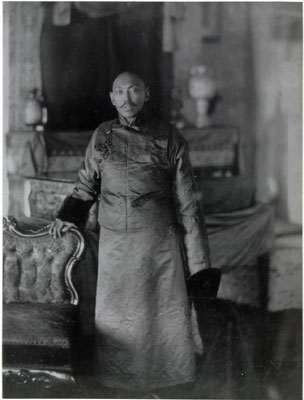

After the unsuccessful expedition on Mount Everest in 1922 and 1924, a span of eight years transpired before a pivotal development occurred. In August 1932, the 13th Dalai Lama provided authorization for an approach to the mountain from its northern side, through Tibet. However, this permission was granted under the stipulation that only British climbers would participate in the endeavor.

The achievement of this permission was the result of a collaborative effort involving the India Office, the government of India, and Lieutenant Colonel J. L. R. Weir, a British political agent in Sikkim. The collective initiative was fueled by a sense of urgency. The British feared that Germans were targeting Everest after prior expeditions to Kanchenjunga and Nanga Parbat.

In the picture: In 1932, the 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso granted the British permission for a new Everest attempt.

1933 Everest Expedition Participants

The Mount Everest Committee, responsible for funding pre-war Everest expeditions, needed to designate an expedition leader. General C. G. Bruce, the most obvious candidate, was unavailable. Two other suitable individuals, both with prior Everest experience, were considered but declined due to commitments: Brigadier E. F. Norton and Major Geoffrey Bruce.

Ultimately, Hugh Ruttledge was selected as the leader, though at forty-eight he was advised not to climb the higher mountain sections due to his age and an old injury. This choice surprised many, including Ruttledge himself, as he lacked extensive cutting-edge mountaineering experience despite being a seasoned Himalayan explorer.

Ruttledge led the recruitment of British climbers for the expedition, assisted by an advisory sub-committee consisting of Norton, T. G. Longstaff, Sydney Spencer, and Geoffrey Winthrop Young. He aimed to enlist experienced Mount Everest veterans. E. O. Shebbeare, who had served as transport officer in 1924, took on the same role again and was also appointed deputy leader. Shebbeare, at forty-nine, held the distinction of being the oldest expedition member. Crawford, a participant in the 1922 Everest expedition, was also part of the team.

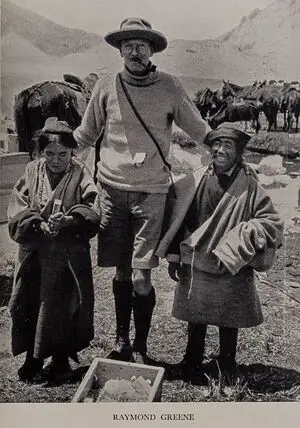

Additional members had prior Himalayan experience, including Eric Shipton, who had scaled Kamet and Mount Kenya, Dr. Raymond Greene, the senior physician of the expedition and a Kamet climber, and Smythe, who had ascended Kamet and joined the international Kangchenjunga expedition with Professor Dyrenfurth. Birnie, previously involved in the Kamet expedition, held the position of transport officer.

The British team for the mountain ascent had sixteen members. Ruttledge believed all, except himself, Shebbeare, and the wireless operators, were chosen for their potential in reaching the summit.

| Name | Role | Profession |

|---|---|---|

| Hugh Ruttledge | Leader | Civil Servant (Indian Civil Service) |

| E.O. Shebbeare | Deputy Leader and Transport Officer | Indian Forestry Service |

| Captain E.St.J. Birnie | Mountaineer | Soldier (Sam Browne’s Cavalry) |

| Major H. Boustead | Mountaineer | Soldier (Sudan Camel Corps) |

| T.A. Brocklebank | Mountaineer | Cambridge Graduate |

| C.G. Crawford | Mountaineer | Civil Servant (Indian Civil Service) |

| Dr. C.R. Greene | Principal Medical Officer and Mountaineer | Doctor |

| J.L. Longland | Mountaineer | English Lecturer at Durham University |

| Dr. W. McLean | Second Medical Officer and Mountaineer | Staff of the Mission to the Jews, Jerusalem |

| E.E. Shipton | Mountaineer | Settler in Kenya |

| W.R. Smijth-Windham | Wireless Operator | Soldier (Royal Corps of Signals) |

| F.S. Smythe | Mountaineer | Freelance Adventurer |

| E.C. Thompson | Wireless Operator | Soldier (Royal Corps of Signals) |

| L.R. Wager | Mountaineer | Lecturer in Geology |

| G. Wood-Johnson | Mountaineer | Tea Planter |

| P. Wyn-Harris | Mountaineer | Civil Servant (Kenyan Civil Service) |

Logistics and Equipment: Support and Provisions

The Mount Everest Committee contributed £5,000 of the estimated £11,000–£13,000 expedition costs. Additional funding came from Ruttledge’s book deal with Hodder & Stoughton, a newspaper arrangement with The Daily Telegraph, and a £100 gift from King George V. Various companies offered equipment either free or at a discount.

The expedition utilized five main types of tents: a sixteen-man mess tent by Silver and Edgington; Muir Mills of Cawnpore bell tents for porters; Camp and Sports six-man arctic tents, termed “real successes” by Ruttledge for their resilience against blizzards; Silver and Edgington Meade tents, plus modified Meade tents from Burns of Manchester. Lightweight emergency tents were also acquired.

Sleeping gear included down sleeping bags from Burns and Silver and Edgington, Jaeger sleeping-sacks, and an emergency shelter bag from Sir George Lowndes. High-altitude leather double-boots came from Robert Lawrie, while approach boots were supplied by John Marlow and Son, and F. P. Baker and Co. Camp boots made of sheepskin and wool were provided by Clarke, Son and Morland. Custom high-altitude goggles and ice equipment were sourced from various suppliers, including Horeschowsky in Austria. Additionally, Kashmir-made puttees, Alpine Club rope, and light line were secured from Beale of London and Jones of Liverpool.

Similar to prior Mount Everest expeditions, supplemental oxygen was a part of the preparations. The strategy was to deploy it exclusively beyond the North Col, and solely in emergencies resulting from unsuccessful acclimatization. Dr. Greene collaborated with the British Association of Oxygen Supply and Siebe, Gorman & Co. to develop a 12.75-pound (5.8 kg) oxygen apparatus. This revised model eliminated the flow meter, instead incorporating a whistle to audibly indicate oxygen flow through the valve.

Preparations for the 1933 Mount Everest Expedition

In January 1933, the main expedition group set sail from England, embarking on a journey that held both logistical preparations and cultural interactions. Their sea route included stops at Gibraltar and Aden, where the team engaged in mountaineering challenges and discussions on Mount Everest’s ascent logistics. While at sea, they focused on organizing the expedition’s camps on the mountain’s northern side and learning Nepali language, facilitated by Crawford’s proficiency.

Arriving in Bombay, the expedition was aided by C. E. Boreham of the Army and Navy Stores. After passing through Calcutta, where they were hosted by Sir John Anderson, the Governor of Bengal, the group continued to Darjeeling. Smythe, Greene, and Birnie joined them there, while Ruttledge coordinated with Shebbeare in Siliguri regarding transportation.

In Darjeeling, porters were selected, including Ruttledge’s Sherpas Nima Dorje and Sanam Topgye, who had informed potential applicants about the British expedition. Key figures such as Llakpar Chedi, Lewa, and Nursang were chosen as sirdars. Experienced individuals like Nima Tendrup and Sherpas from recent German Kangchenjunga expeditions were also included. Karma Paul, an interpreter who had been part of previous British expeditions, joined as well.

The Sherpas underwent health assessments at the Darjeeling hospital, revealing a significant percentage with internal parasites. They were provided with numbered identity disks and outfitted in blue-and-white striped pajamas.

On March 2nd, a significant moment occurred in Darjeeling in front of the Planters’ Club. The expedition team participated in a ceremonial blessing performed by the lamas of Ghoom monastery. This event, Ruttledge noted, left a long-lasting impression due to its quiet yet dignified nature.

The Expedition Route and Encounters on the Way to Mount Everest

The original plan was to take the shortest route to Mount Everest through the Sebu La pass. But due to snow cover, the expedition opted for the longer path via the Chumbi Valley and Phari Dzong. The team initially split into two groups for the journey, with the aim of converging in Gautsa. Notably, Longland and Shipton advanced to organize supplies in Kalimpong ahead of the others.

On March 3rd, those lacking Himalayan experience set out, followed by the second group, which included Ruttledge, Shebbeare, Greene, Smythe, and Birnie, departing on March 8th. At Kalimpong, Pangda Tsang, a Tibetan government trader, advised that the mule-laden baggage train should take the Jelep La route to Kampa Dzong. Consequently, a third group, comprising Smijth-Windham, Thompson, and Karma Paul, accompanied the train, planning to rejoin the second group at Yatung.

Continuing through Pedong and Pakhyong, the expedition reached Gangtok, the capital of Sikkim. Here, Lobsang Tsering’s postal service was established to handle the expedition’s mail and send it to Calcutta. The political agent F. Williamson hosted the expedition and provided them with a passport bearing the Tibetan government’s seal. The passport, intended for fourteen individuals instead of sixteen, initially caused confusion but was resolved through communication with Williamson.

The group had an audience with the Maharaja of Sikkim before proceeding to Karponang, Tsomgo, and crossing the Natu La pass. At this point, four members ascended Chomunko peak (17,500 ft).

Journey Through Challenges: The Expedition’s Path to Kampa Dzong

The expedition descended to Chumbitang and continued to Yatung, passing by the Khajuk monastery where lamas and monks were puzzled by the quest to climb Mount Everest. In Yatung, Captain A. A. Russell, the British trade agent, hosted the team, followed by a polo game organized by Wood-Johnson. The entire group reunited at Gautsa, where Ruttledge designated Shebbeare as “second-in-command.” The weather grew colder, with the first snowfall occurring on the evening of March 22nd.

On March 25th, the party moved past Phari Dzong and navigated a diversion over the Tang La due to snow and strong winds. The route led through Shabra Shubra, Dongka La, Chago La, and finally reached Kampa Dzong on March 29th. From a pass near Kampa Dzong, the team caught their first distant view of Mount Everest, one hundred miles away. The dzong, possessing remarkable architectural beauty, was where Ruttledge donned Tibetan formal attire to meet the nyapala, successfully forging friendly negotiations.

The nyapala extended an invitation to explore the dzong. With advance stores, yaks, and Longland (the quartermaster) at Kampa Dzong, the organization proceeded. Departing on April 2nd, the expedition journeyed through Lingga and Mende en route to Tengkye Dzong. A football match and exhibitions by Boustead and Longland provided moments of recreation. Leaving Tengkye Dzong on April 5th, the party advanced to Khengu via the Bahman Dopté pass. Lopsang Tsering, while at Khengu, suffered a fall from his pony, breaking his collarbone. Anesthesia administered by Greene briefly stopped his heart, but resuscitation efforts, aided by coramine, saved his life.

Journey to Shekar Dzong and the First Glimpse of Mount Everest

The expedition continued its journey, crossing the Chiblung-Chu river twice and stopping at Jikyop. Progressing through Trangso-Chumbab and Kyishong, they navigated a landscape reminiscent of “mountains of the moon,” arriving at Shekar Dzong. Ruttledge characterized Shekar Dzong as a magical place with white houses and monasteries, albeit marred by a smallpox epidemic.

Unfortunately, equipment and supplies, including high-altitude boots and a Meade tent, were stolen, resulting in flogging for the baggage train drivers despite the thief eluding capture. The Arctic tents were first pitched at Shekar, winning general approval, and a successful hair-cutting session was held, led by Wyn-Harris.

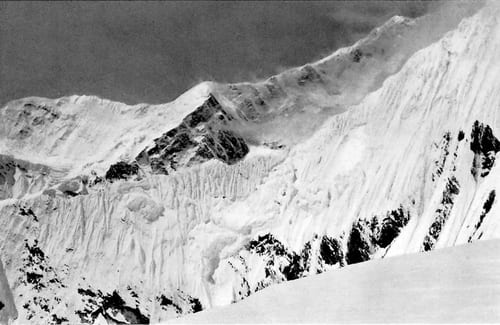

On April 13th, the party continued, crossing the 17,000 ft Pang La before descending to Tashidzom, where the ponies were stabled. The group reached Chö-Dzong on April 15th. From an elevated vantage point, a clear view of Mount Everest was obtained through a naval telescope. The north face seemed relatively snow-free, revealing Norton’s traversed ledges, appearing challenging but feasible. The overhanging Second Step presented an obstacle, and though the summit slopes seemed achievable, reaching them across the daunting couloir walls posed a significant challenge.

Ruttledge documented this first close and detailed mountain view:

“Darkness began to fall as long clouds drifted across the summit. We descended to camp in a mood of qualified optimism. At least we had been able, for the first time, to see for ourselves, to form a judgement of our own, and from a distance which allowed a fairly true perspective. Henceforth we should be too far under the mountain to estimate our difficulties with any accuracy.”

– Hugh Ruttledge

Marching through the Rongbuk valley towards Rongbuk Monastery, the expedition encountered numerous Tibetans moving from the monastery. Interpreter Karma Paul sought an audience with the monastery’s lama to secure his blessing, deemed important for both Tibetan and Nepali porters. The lama, upon blessing each expedition member individually, posed a question to Ruttledge about his relation to General Bruce, leader of the preceding expedition. The blessings were performed with the touching of heads using a dorje, accompanied by the chant “Om mani padme hum”.

Setting Up Camps and Infrastructure for the Expedition

On April 17th, Base Camp was set up four miles beyond Rongbuk Monastery, following the tradition of previous expeditions. Several team members fell ill upon arrival: Crawford with bronchitis, Wyn-Harris with influenza, and Thompson with heart trouble. A porter was diagnosed with double pneumonia, prompting Crawford, Maclean, and Ondi to descend to Rongbuk for treatment. Despite the setbacks, efforts were invested in establishing lower camps. A key principle was to fully equip each camp before ascending to a higher one, ensuring their sustainability during adverse weather rather than abandonment.

The wireless equipment, managed by Smijth-Windham and Thompson, was quickly operational, picking up a signal from Darjeeling on April 20th. A dedicated “wireless room” was established in a tent, complete with two wireless masts, a wind generator, and a petrol engine. Base Camp’s money chests were safeguarded by Gurkha soldier Havildar-Major Gaggan Singh, supported by NCOs Lachman Singh and Bahadur Gurung, who supervised the glacier camps.

To relieve the high-altitude porters, local Tibetan labor from Shekar Dzong up to Camp II was employed. Camp I was established on April 21st, located 400 yards (365m) from the East Rongbuk glacier. Smythe, Shipton, Birnie, Boustead, Wood-Johnson, and Brocklebank spent a night there.

Subsequently, Camp II was set up at 19,800 ft (6035m) on the western side of the East Rongbuk glacier on April 26th by Smythe, Shipton, Boustead, and Wood-Johnson. This camp was designed as a central hub, capable of accommodating around forty individuals with erected tents, serving as a pivotal communication point.

Ascending Challenges: Establishing Camps and Tackling the North Col

On May 2nd, Camp III was established by a team including Smythe, Shipton, Birnie, Boustead, Wood-Johnson, and Longland, along with porters. The camp was situated at an elevation slightly above 21,000 ft (6400m). It was designed to operate independently from Base Camp, ensuring swift supply to higher camps.

The North Col, visible from Camp III, presented the “first serious mountain problem,” according to Ruttledge. This steep glacier ice-fall is constantly in motion, with its navigable path one year potentially obstructed by crevasses or ice-cliffs the next. Cognizant of the 1922 expedition tragedy that claimed seven porters due to an avalanche, the team approached the 1,000 ft ice wall leading to the North Col cautiously.

To mitigate the ice wall’s challenges, Camp IIIa was established at its base. As the original route taken by the 1924 expedition proved unfeasible, the same path used in 1922 was chosen, leading to a shelf below the col. This spot was earmarked for Camp IV. Between May 8th and 15th, Smythe, Shipton, Greene, Longland, Wyn-Harris, Wager, and Brocklebank climbed the slope, setting fixed ropes. Each day, the cut steps filled with snow, complicating re-ascent. On May 12th, Smythe and Shipton successfully reached the ledge using combined tactics, and on the following day, Longland and Wager secured the rope ladder provided by the Yorkshire Rambling Club.

Due to adverse weather, Camp IV couldn’t be established until May 15th. Subsequently, Crawford and Brocklebank undertook six ascents and descents of the North Col slopes, ensuring a secure position for the higher party. This dedicated effort, as noted by Ruttledge, made the Camp IV position robust despite challenging conditions.

High Aspirations and Harsh Realities: Challenges of Establishing Higher Camps

Upon reaching the North Col, progress in establishing higher camps became feasible. However, disputes arose regarding the location of Camp V. A party including Wyn-Harris, Birnie, and Boustead departed for a higher point, but eventually left their stores on the slope and returned to Camp IV. Ruttledge intervened after learning of the situation and sent a team onwards to establish Camp V at 25,500 ft, planning for Camp VI to follow the next day.

Camp V was successfully pitched at 25,700 ft on May 22nd. Among discoveries near the campsite were George Finch’s shredded Meade tent from the 1922 attempt, functional oxygen cylinders, and an unopened canister of Kodak film. Greene, initially expected to ascend further, descended due to heart issues, and Wager took his place, joining Wyn-Harris.

Dismal weather persisted on May 23rd and 24th. In the absence of signs of progress above, Ruttledge, Wager, Wyn-Harris, Longland, and Crawford ascended to investigate. At 24,200 feet, Wager and Wyn-Harris learned from Smythe that Camp V had been abandoned, prompting a descent. The severe conditions during the descent led to frostbite among several Sherpas, including Lakpa Chedi who later required finger amputation. Additionally, Birnie, attempting a glissade down the north face, narrowly avoided a fatal incident with the help of Da Tsering’s intervention.

Pioneering Ascent: Wager and Wyn-Harris’s Climb towards the Summit

On May 30th, at 5:40 a.m., Wager and Wyn-Harris began their ascent from Camp VI, following an hour spent preparing and having a modest meal. During their climb, they encountered an ice-axe lying on rocky slabs below the north-east ridge. It was marked with “Willisch of Täsch,” an equipment maker from Zermatt.

They left it in place but retrieved it during their descent. Ruttledge’s book “Everest 1933” suggests that this axe likely belonged to Andrew Irvine. This was supported by the fact that the notches on it match those on his swagger stick.

The climbers’ initial focus was on assessing the climbability of the Second Step on the ridge. They bypassed the First Step and proceeded under the Second Step, unaware that it was shielded by cliffs from below. In an attempt to ascend, they aimed for a gully they believed led to the top of the Second Step. However, discovering it to be shallow, they followed Norton’s 1924 traverse above the yellow band on the north face, eventually reaching the Great Couloir by 10:00 a.m.

Second Ascent: Shipton and Smythe

Shipton and Smythe remained at Camp VI, awaiting the return of Wager and Wyn-Harris. Unfortunately, Shipton fell ill and reached his physical limit, compelling him to halt his ascent. Following a brief conversation with Smythe, Shipton made the decision to descend back to Camp VI.

Meanwhile, Smythe, undeterred, continued onward alone. Around 28,120 feet, which was approximately the same elevation as that reached by Wager and Wyn-Harris, Smythe chose to turn back from his ascent.

Critical Analysis of the Expedition and Factors Influencing its Outcome

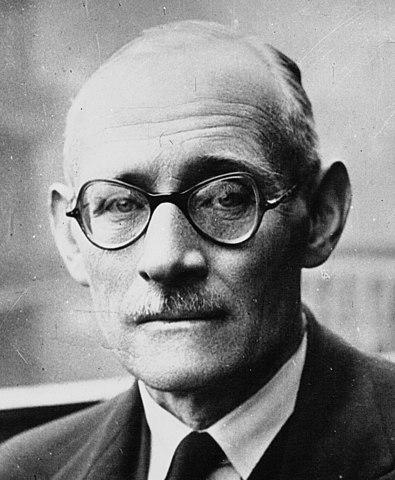

The inquiry commissioned by the Mount Everest Committee to investigate the expedition’s shortcomings concluded that while Ruttledge was held in high regard and well-liked, his leadership style lacked assertiveness.

In his evaluation of “Everest 1933” (authored by Ruttledge, first published in 1934), G. L. Corbett praised the book, describing it as having “passages as fine as anything in Alpine literature.” While recognizing the meticulous preparation and methodical direction of the expedition, Corbett identified three key factors contributing to its failure to conquer Mount Everest’s summit.

Firstly, the dispute over Camp V’s placement and the subsequent descent to Camp IV resulted in the loss of a crucial climbing window from May 20 to 22. Raymond Greene later remarked that this setback might have cost them not just two days, but two decades. Following this, the weather worsened significantly. Corbett held Ruttledge accountable for this misjudgment, arguing that Ruttledge should have remained at Camp IV to oversee operations instead of being positioned lower on the mountain.

Secondly, directing Wager and Wyn-Harris to climb the Second Step delayed their progress. Even though they eventually opted for Norton’s lower traverse, their earlier attempts at the Step consumed valuable time. Their lack of conviction regarding the climbability of the Step underscored the importance of resolute decision-making. Corbett quoted Smythe’s perspective that conquering Everest required single-minded commitment to the chosen route, as any uncertainty could lead to failure.

Lastly, Corbett highlighted that Smythe’s solo attempt was a consequence of Shipton falling ill during the ascent. Corbett criticized solo climbing in hazardous conditions, arguing that such an approach was unfavorable, particularly on Everest’s treacherous final section.

Shipton’s Critique of the 1933 Expedition Size and Composition

In his book “Upon that Mountain” (1943), Shipton critiqued the size of the expedition, deeming the inclusion of fourteen climbers as excessive. He countered the argument that reserve climbers were essential for illness, noting that no capable high-altitude climbers fell sick before the attempt.

He criticized the large group’s negative psychological impact, where climbers felt redundant for the goal of placing only a few on the summit, causing strain, friction, and inefficiency. Shipton proposed smaller expeditions where each member recognized their significant role. His stance, including his 1952 statement to the Mount Everest Committee, influenced his exclusion from leading the successful 1953 expedition due to his aversion to large expeditions and competitive aspects in mountaineering.

Forging a Legacy: The 1933 British Mount Everest Expedition

In the annals of mountaineering history, the 1933 British Mount Everest Expedition remains a significant chapter. Laden with both achievements and setbacks, this endeavor showcased the intricate interplay of ambition, strategy, and the unpredictable forces of nature.

With meticulous preparation, the expedition aimed to conquer the world’s highest peak, but challenges such as disagreements over camp placements, adverse weather, and individual health hindered their ascent.

The expedition’s legacy, however, extends beyond its unattained summit, shaping future mountaineering philosophies. Lessons from its successes and failures, continued to influence the approach to mountaineering expeditions. They emphasized teamwork, efficiency, and a shared sense of purpose as essential elements in the quest to summit Everest.