Jim Whittaker, a native of Seattle, transformed his deep-rooted passion for nature and a craving for adventure into a series of groundbreaking accomplishments. His legacy includes several pioneering feats:

- He etched his name in history as the first American to conquer Mount Everest.

- His journey with Recreational Equipment, Inc. (REI) began with his role as its inaugural full time employee, culminating in his ascension to the position of CEO.

- Additionally, he spearheaded the inaugural U.S. expedition that achieved a triumphant ascent of K2, the Earth’s second-highest peak.

Even at the age of 60, Whittaker continued to lead by example, spearheading the International Peace Climb, a milestone undertaking that stands as the most successful Everest expedition in recorded history.

Whittaker attributes his achievements to the foundational values instilled by the Boy Scouts during his formative years. This upbringing nurtured his environmental awareness and imparted vital skills such as camping, hiking, and climbing. Furthermore, he acknowledges his mother’s influence, as she cultivated his willingness to embrace risk and seize opportunities.

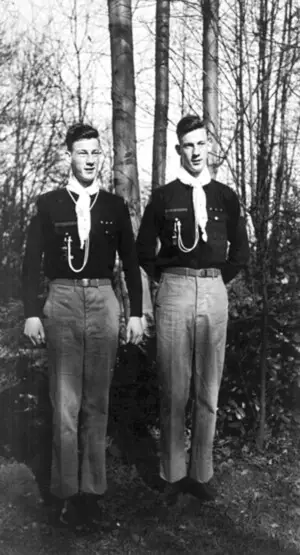

The Journey of ‘twins’ Jim and Lou Whittaker

James W. “Jim” Whittaker was born February 10, 1929, arriving 10 minutes ahead of his twin brother, Lou. Raised alongside their elder brother Barney, the trio spent their formative years in the Arbor Heights neighborhood of West Seattle. Their parents, Hortense Elizabeth and Charles Bernard Whittaker, were rooted in rather unusual vocations—Charles was engaged in the sale of bank alarms and vault doors.

Energized by a thirst for adventure, the twins exhibited their vibrant spirits by enlisting in Boy Scout Troop 272 at the age of 12. They furthered their exploration by joining the Explorer Scouts at the age of 14, and 16. They also became active members of The Mountaineers club. Progressing from West Seattle High School, their educational journey continued at Seattle University, with Jim focusing on a biology major while concurrently delving into philosophy. Nonetheless, their passions leaned predominantly toward the allure of mountains and the challenges they posed.

Even amid their collegiate pursuits, the twins relentlessly pursued their alpine ambitions. Their involvement extended to the National Ski Patrol, and they played pivotal roles as charter members of the Northwest Mountain Rescue and Safety Council. Notably, their expertise expanded to serving as professional guides on the slopes of Mount Rainier.

Whittaker’s Journey: REI’s Phenomenal Growth

At 25, Jim Whittaker seized a chance that led to monumental success. Lloyd Anderson founded the Recreational Equipment Co-operative (REI) in 1938 to aid Northwest climbers in accessing European gear. With 600 members and $80,000 in yearly sales, Anderson recognized Whittaker’s potential and offered him a managerial role, providing a $400 monthly salary and a half-percent commission on sales.

Whittaker assumed this role on July 25, 1955, succeeding a departing part-timer. For seven months, he singlehandedly managed the co-op from a downtown Seattle office. REI officially became Recreational Equipment, Inc., in 1956, spurring rapid expansion.

By 1960, Anderson became full-time manager, leaving Whittaker in charge of sales. When Anderson retired in 1971, Whittaker took the reins, elevating REI to a $46 million enterprise with 700 employees and nationwide branches over eight years.

From Modest Beginnings to Everest

In the midst of operating within a compact 20- by 30-foot space, REI was laying the groundwork for its future success. Meanwhile, the Whittaker twins, who had already achieved the summit of Mount Rainier numerous times and conquered Mount McKinley – North America’s towering pinnacle at 20,320 feet – were harboring aspirations for even greater challenges.

Their opportunity arrived in the early months of 1961. The catalyst was Norman Dyhrenfurth, a prominent mountaineer, who also held the role of director. Dyhrenfurth extended an invitation to the twins to join an expedition in 1963. It aimed at achieving the extraordinary feat of conquering Mount Everest – a milestone that no American had previously accomplished. At that juncture, only nine men had reached the summit, a journey initiated by Edmund Hillary in 1953.

With their extensive mountaineering background and credentials, the Whittaker twins were primed for this journey. Jim Whittaker, due to his association with REI, was entrusted to serve as the expedition’s equipment coordinator. This appointment underscored the significance of his connection to the outdoor equipment cooperative in shaping the trajectory of his mountaineering career.

In September 1962, the team started preparations on Mount Rainier as a part of their training regimen. As departure for the impending expedition drew near, a significant development occurred. Lou Whittaker, made the decision not to participate. This choice stemmed from his commitment to opening a sporting goods store in Tacoma alongside some partners.

Surprisingly, Jim Whittaker, received this news from one of Lou’s associates and not directly from his brother. This unforeseen turn of events took an emotional toll on Jim, given their extensive shared history and meticulous two-year planning for the Everest expedition. Jim’s reaction was one of anger and a sense of betrayal, emotions that he candidly detailed in his autobiography – Whittaker, Life on the Edge (affiliate link!) – describing the experience as a “stunning blow”

The American Mount Everest Expedition of 1963

Jim Whittaker stood out among the 20 members of the American Mount Everest Expedition, not necessarily as the most accomplished climber, but due to his imposing size and strength, coupled with his determination. A critical indicator of his resolute mindset emerged during psychological testing in early January 1963 before their departure.

When prompted to express their expectations of reaching the summit, the team members, considering the uncertainties of high-altitude conditions, generally responded with expressions of uncertainty or hope. Remarkably, only Whittaker unequivocally stated his conviction that he would reach the top.

The ambitious expedition started from Kathmandu on February 20. The expedition came with a substantial price tag, exceeding $400,000, equivalent to roughly $2.8 million. The National Geographic Society emerged as the primary sponsor, contributing more than a quarter of the total funds.

With a cargo of 27 tons comprising both food and equipment, a contingent of around 900 porters, and 32 Sherpas known for their exceptional climbing skill, the expedition commenced its journey. The expedition initiated its course with a 15-mile truck ride, followed by a 170-mile trek on foot towards Everest. This arduous hike, forming what Whittaker vividly described as “a mile-long millipede,” spanned a duration of one month.

The Final Summit Push

Tragedy struck the American Mount Everest Expedition just two days after establishing a base camp at 17,800 feet. John E. Breitenbach, a climber from Wyoming, lost his life in a tragic incident while navigating the most treacherous segment of the glacier. The fatal accident occurred when he was trapped under massive blocks of ice.

Despite the profound shock of this loss, the expedition members regrouped and continued their mission. On April 17, they embarked on the task of provisioning upper camps, often led by Jim Whittaker who pioneered the trails. Whittaker’s climbing partner was Nawang Gombu, the nephew of Tenzing Norgay – the legendary Sherpa who had achieved the Everest summit with Edmund Hillary in the historic 1953 expedition.

In their relentless pursuit of the summit, Whittaker, Gombu, expedition leader Norman Dyhrenfurth, and Sherpa Ang Dawa formed the initial summit team. Reaching the highest camp at an elevation of 27,450 feet on April 30, they spent a night in fierce storms. Undeterred by 60 mile-per-hour winds and temperatures plummeting to minus-30 degrees, Whittaker remained resolute, feeling that he could not turn back after coming so far.

The following morning, around 6:15 a.m. on May 1, Whittaker and Gombu exited their tent and ventured into an intense ground blizzard, so intense that visibility was virtually nonexistent. In this harsh environment, they resorted to a combination of climbing and crawling to proceed.

Conquering Everest: Jim Whittaker’s Historic Summit and Its Impact

At 1 p.m., they triumphantly reached the summit, covering the final 50 feet side-by-side despite being devoid of oxygen. Whittaker’s two water bottles had frozen solid, and he bore frostbite in one eye despite donning goggles. He planted the American flag into the icy ground and captured photographs with Gombu.

Within a brief 20-minute interval atop the summit, they made their way back to 27,450 feet where Dyhrenfurth and Dawa were awaiting their return. Dyhrenfurth later marveled at Whittaker’s superhuman feat under such dire conditions, deeming it miraculous. The extreme severity of the circumstances suspended any further summit attempts for a duration of three weeks.

In adherence to Dyhrenfurth’s stipulation, climbers’ names who reached the summit were to be disclosed only after all assault teams had their opportunity. On May 2, news was relayed from base camp to Kathmandu, revealing that two climbers, referred to as ‘a big one and a little one’, had successfully reached the top.

Amid fervent media inquiries and expedition delays due to adverse weather, Dyhrenfurth eventually yielded. On May 9, he transmitted Whittaker’s and Gombu’s identities via radio, promptly disseminated by wire services.

During the same expedition, four additional Americans accomplished the Everest summit. Barry Bishop of Ohio and Lute Jerstad from Oregon emulated Whittaker’s ascent via the South Col, accomplishing the feat approximately three weeks after Whittaker and Gombu. On the same day, Willi Unsoeld, and Tom Hornbein, achieved the summit through the previously unconquered West Ridge of Everest. Following their successful ascent, Bishop and Unsoeld experienced severe frostbite, leading to the loss of several toes for each.

Nonetheless, it was Whittaker’s name that resonated in the collective memory. Reflecting in his autobiography, he realized that his life had irrevocably transformed, stating, “Gradually it dawned on me that my life had changed forever.”

Triumphant Return and Presidential Recognition

On June 24, Jim Whittaker returned to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport alongside two fellow climbers from the expedition, Luther G. “Lute” Jerstad and Barry Prather. Jerstad, a Mount Rainier guide, had successfully summited Everest on May 22, while Prather was an aeronautics engineer from Ellensburg.

The triumphant trio received a hero’s welcome, accompanied by their families, as they rode in open convertibles through downtown Seattle. The procession was met with crowds lining 4th Avenue, and colorful streamers cascading from office building windows added to the celebratory atmosphere.

Subsequently, on July 8, a notable ceremony took place in the Rose Garden of the White House. During this event, President John F. Kennedy presented the highest accolade of the National Geographic Society, the Hubbard Medal, to each member of the Everest expedition, recognizing their remarkable achievements.

Jim Whittaker’s Role in the 1990 International Peace Climb

In 1990, Jim Whittaker embarked on a new mountainous endeavor by leading an international expedition to Everest. This initiative aimed to unite climbers from historical Cold War adversaries – China, the Soviet Union, and the United States. The aim was to showcase the potential of trust and collaboration. Whittaker’s vision was a prelude to diplomatic shifts like glasnost and perestroika, marking a unique summit of cooperation amid adversarial pasts.

Heading the International Peace Climb demanded extensive diplomacy. Overcoming challenges, including persuading skeptical officials in both China and the Soviet Union, Whittaker orchestrated a team of 30 climbers, each country contributing five representatives. However, a leg injury temporarily sidelined him during the establishment of camps.

Upon his return, Whittaker played a vital role in mediating disputes, navigating linguistic complexities, and facilitating negotiations. Despite internal conflicts, the Peace Climb set an unprecedented record as the most successful Everest expedition ever.

A total of 20 climbers successfully reached the summit, including Ed Viesturs, a Seattle veterinarian and Mount Rainier guide, who later achieved the distinction of climbing the world’s 14 highest peaks without supplemental oxygen. Reflecting on the achievement, Viesturs credited Whittaker’s leadership as the unifying force that held the expedition together.