The 1953 British Mount Everest expedition marked the ninth endeavor to achieve the inaugural ascent of Mount Everest. This daring Everest Expedition, led by Colonel John Hunt and funded by the Joint Himalayan Committee, saw its ultimate triumph when Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary reached the summit on 29th May.

The momentous news of their successful ascent reached London just in time for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation on 2nd June of the same year. This historic achievement solidified the expedition’s place in mountaineering history.

Historical Context of the Everest Expedition

In the 1850s, Mount Everest gained recognition as the highest mountain in the world, capturing the imagination of adventurers during the Golden Age of alpinism. With its remarkable height, the feasibility of climbing it remained uncertain. However, in 1885, Clinton Thomas Dent’s work “Above the Snow Line” suggested the possibility of an ascent.

Unfortunately, practical considerations and the outbreak of World War I hindered any significant attempts until the 1920s. It was during this time that George Mallory expressed his desire to conquer Everest, famously stating, “Because it’s there” – a phrase that would go on to be hailed as “the most famous three words in mountaineering.”

Tragically, Mallory met his fate during the 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition, and for 75 long years, his disappearance remained an enigma. Despite the challenges and uncertainties surrounding Everest, the allure of the mountain persisted, beckoning intrepid souls to test their mettle against its awe-inspiring heights.

Initially, the majority of early attempts on Everest centered on the northern (Tibetan) side. However, the course of history took a turn with the Chinese Revolution of 1949, leading to the closure of this route due to Tibet’s annexation. Subsequently, climbers redirected their focus towards exploring an approach from the Nepalese side.

In 1952, the Swiss Mount Everest Expedition ventured from Nepal and accomplished a significant feat, reaching an elevation of approximately 8,595 m (28,199 ft) on the southeast ridge. This achievement set a new climbing altitude record and marked a turning point in the quest for conquering the world’s highest peak.

John Hunt and the British Everest Expedition

John Hunt, a British Army Colonel, found himself serving at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe when an unexpected invitation arrived. The Joint Himalayan Committee of the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society invited him to lead the British Everest expedition of 1953. The appointment came as a surprise since many had anticipated Eric Shipton to be the leader, given his previous experience leading the 1951 Mount Everest Reconnaissance Expedition from Nepal and the unsuccessful Cho Oyu expedition in 1952, from which most of the selected climbers were drawn.

However, the committee had a different vision. They believed that Hunt’s combination of military leadership experience and climbing credentials would provide the best chance for the expedition to succeed. The British team faced additional pressure as the French had obtained permission for a similar expedition in 1954, and the Swiss had secured another opportunity in 1955. This meant that the British would not have another chance at Everest until 1956 or later.

Shipton expressed his feelings to the Committee on 28 July 1952, stating that his dislike of large expeditions and aversion to a competitive element in mountaineering might not align well with the current situation. George Band recalled that this statement “sealed his own fate.”

Many members of the British expedition had strong loyalty to Shipton and were dissatisfied with his replacement. Charles Evans remarked that it was rumored Shipton lacked the killer instinct, though he personally didn’t view it as a disadvantage. Edmund Hillary, too, opposed the change initially, but he was won over by Hunt’s personality and his admission that the handling of the change had been flawed. George Band remembered Committee member Larry Kirwan, the Director/Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society, remarking that “they had made the right decision but in the worst possible way.”

Hunt later reflected on the challenge faced by the Joint Himalayan Committee in securing funds for the expedition:

Among the many important responsibilities of the Joint Himalayan Committee, aside from conceptualizing the Everest expedition, obtaining political approval, and making preparatory decisions, was the arduous task of financing it. Only those who have experienced this burden can truly comprehend the relentless efforts and worries involved in raising substantial funds for an endeavor colored in the public’s mind by a series of previous failures. There existed no financial safety net other than the personal contributions of the Committee members themselves.

John Hunt

Training and Departure for the Everest Expedition

In the winter, the initial training phase unfolded in Snowdonia, Wales. The Pen-y-Gwryd hotel served as their base camp, where the team honed their mountaineering skills on the slopes of Snowdon and the Glyderau. The crucial testing of the oxygen equipment took place at the Climbers Club Hut at Helyg, near Capel Curig.

On 12th February, the party embarked on their journey to Nepal from Tilbury, Essex, England, aboard the S.S. Stratheden, bound for Bombay. Unfortunately, Tom Bourdillon, Griffith Pugh, and Hunt couldn’t join at that time; Hunt was suffering from an antrum infection.

The Advance Party, comprising Evans and Alfred Gregory, had flown ahead to Kathmandu on 20th February. Meanwhile, Hillary and Lowe had their distinct routes to Nepal; Lowe traveled by sea, and Hillary by air, as his bees required attention during that busy season. While a sea passage was chosen for its cost-effectiveness, Hunt emphasized that the primary reason was to provide the team with an opportunity to settle down and bond as a cohesive unit, free from discomfort, urgency, or stress that air travel might entail.

Hospitality and Tensions: The Everest Expedition’s Arrival in Kathmandu

Upon reaching Kathmandu, the party found accommodation through the assistance of the British ambassador, Christopher Summerhayes. As there were no hotels in Kathmandu at that time, the embassy staff arranged rooms for them. In early March, a group of twenty Sherpas, carefully selected by the Himalayan Club, also arrived in Kathmandu.

Their crucial role would involve carrying loads to the Western Cwm and the South Col. Led by their experienced Sirdar, Tenzing Norgay, who was attempting Everest for the sixth time and highly regarded as “the best-known Sherpa climber and a mountaineer of world standing” according to Band, the Sherpas played an indispensable part in the expedition.

Despite Tenzing being offered a bed in the embassy, the remaining Sherpas were expected to sleep on the floor of the embassy garage. Feeling disrespected, they expressed their protest the next day by urinating in front of the embassy. This incident highlighted the tensions arising from the disparity in treatment and underscored the significance of fostering mutual respect and understanding during the challenging expedition ahead.

1953 British Mount Everest Expedition:

The first stage of the expedition began on 10th March, as the initial party, accompanied by 150 porters, departed from Kathmandu towards Mount Everest. The second party, along with 200 porters, followed suit on 11th March. Their journey led them to Thyangboche, with the first party arriving on 26th March and the second party on 27th March. Between 26th March and 17th April, the teams engaged in vital altitude acclimation, preparing for the challenging ascent ahead.

Colonel Hunt planned three separate assaults, each involving two climbers. If needed, a third final attempt would follow, allowing for some days of rest to regain strength and replenish their camps. The first two assault plans were unveiled on 7th May. The initial assault party, equipped with closed-circuit oxygen equipment, aimed to reach the South Summit of Mount Everest, and if possible, the ultimate summit.

Comprising Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans, only Bourdillon possessed the expertise to handle the experimental oxygen sets.

The second assault party, utilizing open-circuit oxygen equipment, consisted of the strongest climbing duo: Ed Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. They were to set out from Camp IX, situated higher on the South Col. The third assault party, had it been executed, would have consisted of Wilf Noyce and Mike Ward.

In the event of a failure during the spring expedition, the team had a contingency plan to undertake a post-monsoon autumn attempt. This approach was similar to what the Swiss had pursued in 1952, obtaining permission for a year-round expedition, although their arrival had been delayed and, unfortunately, they missed their chance during that particular season.

Establishing The Base Camp

On 12th April 1953, the “Icefall party” successfully arrived at Base Camp, situated at 17,900 ft (5455 m). As per the schedule, they dedicated the following days to establish a route through the Khumbu Icefall.

Once the path was cleared and secured, teams of skilled Sherpas efficiently transported tons of essential supplies up to Base Camp, laying the groundwork for the upcoming stages of the expedition.

Creating Advanced Camps on Everest

In a planned progression, a series of advanced camps were established, each reaching higher up the mountain. The journey began with Camp II, situated at 19,400 feet (5,900 m), established by the trio of Hillary, Band, and Lowe on 15th April. On 22nd April, Camp III was set up at the head of the Icefall, standing at 20,200 feet (6,200 m). Then, on 1st May, Hunt, Bourdillon, and Evans succeeded in establishing Camp IV, known as the Advance Base, positioned at an altitude of 21,000 feet (6,400 m).

Building on these accomplishments, the team ventured forth to perform a preliminary reconnaissance of the challenging Lhotse Face on 2nd May. As they advanced, Camp V was established at 22,000 feet (6,700 m) on 3rd May. The intrepid pair of Bourdillon and Evans, with support from Ward and Wylie, reached Camp VI at 23,000 feet (7,000 m) on the Lhotse Face on 4th May. Continuing their determined ascent, on 17th May, Wilfrid Noyce and Lowe established Camp VII at an impressive height of 24,000 feet (7,300 m).

With every step, the team inched closer to their ultimate goal. By 21st May, Noyce and Sherpa Annullu, the younger brother of Da Tenzing, reached the South Col, an altitude of just under 26,000 feet (7,900 m).

The First Ascent Attempt on Mount Everest

On 26th May, the first climbing pair selected by Hunt, Tom Bourdillon, and Charles Evans, embarked on their ascent towards the summit. They achieved the remarkable feat of reaching the 8,750 m (28,700 ft) South Summit at 1 pm, coming tantalizingly close to the final summit, within just 100 m (300 ft).

Between the South Summit and the true summit, they encountered a thin crest of snow and ice on rock, including the famous Hillary Step. Before starting, Evans faced a setback with a damaged valve in his oxygen set, taking over an hour to fix. Despite this obstacle, they managed an unprecedented ascent rate of almost 1,000 feet (300 m) per hour. However, at 28,000 feet (8,500 m) when they changed soda lime canisters, Evans’ set experienced another issue that Bourdillon couldn’t resolve. Despite Evans’ efforts, his breathing became laboriously painful.

Regrettably, due to a combination of issues with the closed-circuit oxygen sets and limited time, they had to turn back at 1.20 pm, unable to proceed further. The attempt was a valiant one, but the challenges proved insurmountable on this particular day.

Hillary and Tenzing Conquer Everest

On 27th May, the expedition launched its second assault on the summit, featuring Edmund Hillary from New Zealand and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay from Nepal. Notably, Norgay had previously reached a record high point on Everest as part of the Swiss expedition in 1952. They set out from Camp IX at 6:30 am, reached the South Summit at 9 am, and accomplished their goal by reaching the summit at 11:30 am on 29th May 1953, following the South Col climbing route on Everest.

After reaching the summit, Hillary and Tenzing spent some time taking photographs and leaving behind a symbolic gesture: burying sweets and a small cross in the snow. Notably, they did not utilize open-circuit oxygen sets at the summit. Hillary, without his oxygen set for about ten minutes, noticed his dexterity and movements slowing down, demonstrating the challenges of climbing at such high altitudes without bottled oxygen.

On their return from the summit, Hillary’s first words to George Lowe were, “Well, George, we knocked the bastard off,” declaring their success. To preserve the emotional impact of the moment, Stobart ensured that the descending party gave no indication to those at Advance Base (Camp IV), including Hunt and Westmacott, who were eagerly awaiting news. Only when the climbers were within sight did Stobart capture the powerful emotions of the triumphant moment on film.

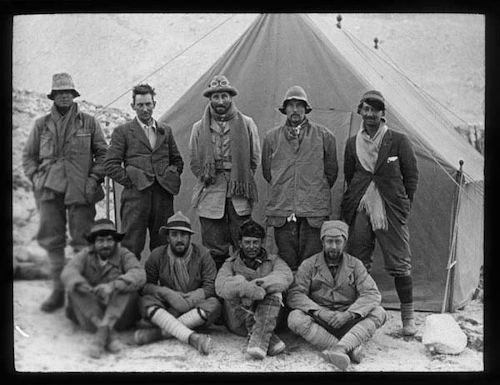

1953 British Mount Everest Expedition Participants

Members of the expedition were chosen based on their mountaineering expertise as well as their proficiency in offering essential skills and support services. The team comprised individuals primarily from the United Kingdom, with additional participants hailing from other countries within the British Empire and the Commonwealth of Nations.

| Name | Role | Profession | Age (time of expedition) |

|---|---|---|---|

| John Hunt | Expedition Leader and Mountaineer | British Army Colonel | 42 |

| Charles Evans | Deputy Expedition Leader & Mountaineer | Physician | 33 |

| George Band | Mountaineer | Graduate in Geology | 23 |

| Tom Bourdillon | Mountaineer | Physicist | 28 |

| Alfred Gregory | Mountaineer | Director of Travel Agency | 39 |

| Wilfrid Noyce | Mountaineer | Schoolmaster & Author | 34 |

| Griffith Pugh | Doctor & Mountaineer | Physiologist | 43 |

| Tom Stobart | Cameraman & Mountaineer | Cameraman | 38 |

| Michael Ward | Expedition Doctor & Mountaineer | Physician | 27 |

| Michael Westmacott | Mountaineer | Statistician | 27 |

| Charles Wylie | Organizing Secretary & Mountaineer | Soldier | 32 |

| George Lowe | Mountaineer | Schoolmaster | 28 |

| Edmund Hillary | Mountaineer | Apiarist | 33 |

| Tenzing Norgay | Mountaineer & Guide | Guide | 38 |

| Sherpa Annullu | Mountaineer & Guide |

The mountaineers were joined by Jan Morris (then known as James Morris), the correspondent of The Times newspaper in London, during their expedition. Additionally, they were accompanied by 362 porters, resulting in a team of over 400 individuals. This group included twenty Sherpa guides from Tibet and Nepal, and carried a total weight of ten thousand pounds of baggage throughout their journey.

Celebrating the Success of 1953 British Mount Everest Expedition

Upon their return to Kathmandu a few days later, the expedition received remarkable honors. Hillary was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire, and Hunt was granted a Knighthood Bachelor, both in recognition of their extraordinary efforts. On 22nd June, the Government of Nepal hosted a reception for the expedition members, during which the senior queen of Nepal presented Tenzing with a purse of ten thousand rupees, equivalent to about £500 at that time. Hillary and Hunt received kukris in jeweled sheaths, while the other members were presented with jeweled caskets.

Additionally, on the same day, the Indian government announced the establishment of a new Gold Medal, an award for civilian gallantry inspired by the George Medal. Hunt, Hillary, and Tenzing were named the inaugural recipients of this prestigious honor. However, it was also announced that Tenzing would be awarded the George Medal by Queen Elizabeth II, following consultations with the governments of India and Nepal. While some commentators criticized this as a lesser honor, implying discrimination, others pointed out that many other Indians and Nepalis had previously received knighthoods. Some suggested that the Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, might have declined permission for Norgay to be knighted, which led to the George Medal award instead.

In July 1953, upon his return to London, Hunt received his knighthood, adding to the recognition and accolades bestowed upon the successful Everest expedition.

Continuing Honors and Controversy

The members of the Everest expedition continued to receive further honors, recognizing their incredible achievement. The National Geographic Society awarded the prestigious Hubbard Medal, a first-time team award, along with individual bronze medals to Hunt, Hillary, and Tenzing. Other accolades included the Cullum Geographical Medal from the American Geographical Society, the Founder’s Medal from the Royal Geographical Society, and the Lawrence Medal from the Royal Central Asian Society. Additionally, honorary degrees were conferred upon them by the universities of Aberdeen, Durham, and London.

In the 1954 New Year Honors list, George Lowe was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for his contributions to the expedition. All 37 members of the team were also honored with the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal, engraved with “MOUNT EVEREST EXPEDITION” on the rim.

The expedition’s cameraman, Tom Stobart, created a documentary titled “The Conquest of Everest,” which was released later in 1953 and earned a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Amidst the celebration, intense speculation arose over who had been the first to step onto the summit of Everest, with Hillary and Tenzing both representing it as a team effort. In Kathmandu, a large banner depicted Tenzing seemingly assisting a “semi-conscious” Hillary to the summit, fueling the controversy. Ultimately, Tenzing put an end to the speculation in his 1955 autobiography, “Man of Everest,” revealing that Hillary had been the first to reach the summit. Hillary later affirmed this, recounting that after ascending the 40-foot Hillary Step, just below the summit:

“I continued on, cutting steadily and surmounting bump after bump and cornice after cornice looking eagerly for the summit. It seemed impossible to pick it and time was running out. Finally I cut around the back of an extra large lump and then on a tight rope from Tenzing I climbed up a gentle snow ridge to its top. Immediately it was obvious that we had reached our objective. It was 11.30 a.m. and we were on top of Everest!”

Edmund Hillary

1953 British Mount Everest Expedition

The 1953 British Mount Everest Expedition stands as an iconic milestone in mountaineering history, marking the triumphant moment when Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay achieved the first summit of Everest. Confronting treacherous terrains, unpredictable weather, and daunting altitudes, they overcame numerous challenges to etch their names in history. Their successful conquest not only redefined human limits but also inspired generations of adventurers worldwide.

The legacy and extraordinary achievement of Edmund Hillary, Tenzing Norgay, and the 400 plus individuals involved in the expedition, will continue to resonate as a testament to their indomitable spirits and thirst for adventure!