Tom Hornbein is most renowned for his daring achievement in 1963 when he successfully ascended the West Ridge of Mount Everest alongside Willi Unsoeld. However, his legacy extends beyond his mountaineering feats. With his life being equally defined by his compassionate and affectionate relationships with numerous individuals.

Born on November 6, 1930, Hornbein’s affinity for heights became evident during his childhood. He frequently found himself drawn to climbing trees and even scaling the slate roof of his family’s house. This inclination led him to the realization that a deep-seated urge to elevate oneself was ingrained within him.

Early Life of Tom Hornbein

Tom Hornbein’s fascination with mountains led him to enroll at the University of Colorado Boulder. Where he enthusiastically embraced rock climbing as an active pursuit. During his undergraduate years, he devoted a significant portion of his time to climbing. Occasionally even skipping classes and labs to do so.

In the summer months, he returned to the Cheley Colorado Camps, where he had previously been a camper. During this time, he forged a lasting friendship with Nick Clinch. This camaraderie evolved into a lifelong connection.

This friendship later proved pivotal as Nick Clinch played a crucial role in introducing Hornbein to the challenges of climbing in the mountain ranges of South Asia.

After completing medical school in 1956, Tom Hornbein ventured to Alaska in 1957 with the aim of embarking on the inaugural ascent of Mount Huntington. He participated in an expedition led by Fred Beckey, alongside climbers like John Rupley and Herb Staley.

Their objective was to conquer Mount Huntington, although challenging snow conditions hindered their progress on the French Ridge. Which was later named after Lionel Terray who accomplished the first ascent in 1964. While snow conditions thwarted their primary goal, the team also endeavored to ascend the Moose’s Tooth. They also managed to complete the second ascent of Mount Barrille.

The Masherbrum Expedition of 1960

In 1960, Tom Hornbein received an invitation from his childhood friend Nick Clinch to join an expedition to Masherbruman. An unclimbed peak at 25,659 feet in Pakistan. The team, led by Clinch, consisted of noteworthy climbers like George Bell (who was part of the 1953 American K2 attempt), Captain Jawed Akhter, Captain Imtiaz Azim, Richard Emerson, Thomas McCormack, Richard McGowan, Captain Akram Quereshi, and William Unsoeld.

Masherbrum had already drawn several attempts before this expedition. In 1938, a British party had reached a high point on the southeast face. In 1955, a New Zealand group halted their endeavor at the base of the same face. Finally, in 1957, a Manchester, England party came just 300 feet shy of the summit. The team, including Hornbein, followed the route on the southeast face that others had attempted. Characterized by steep snow slopes prone to avalanches.

During the climb, a significant surface slide occurred, engulfing the entire party and causing them to tumble towards the cliffs below. Unsoeld and Bell managed to halt the slide and save the group, including Hornbein, who slid about 200 feet.

As they geared up for the first summit attempt, a mishap occurred. Akhter slipped and began hurtling down the slope. In a gripping moment, Hornbein reacted swiftly by grabbing Akhter’s rope with one hand while clinging to the fixed line with the other. Despite the perilous situation, Hornbein’s strength held them both. However, this incident, combined with Emerson’s recurring coughing issues, compelled them to descend. Hornbein’s responsibilities as a doctor also prevented him from making a summit bid.

Ultimately, on July 6th, the first ascent of Masherbrum was achieved by Bell and Unsoeld, followed two days later by Clinch and Akhter.

Tom Hornbein’s Everest Expedition in 1963

Following his completion of a medical research fellowship with the National Institutes of Health in Saint Louis, Tom Hornbein relocated to San Diego. He would serve as an anesthesiologist for the Navy, fulfilling a two-year commitment. During this period, he received an invitation to participate in an American expedition to Mount Everest in 1963. With assistance from friends connected to the Kennedy Administration, Hornbein secured an early discharge to join the expedition.

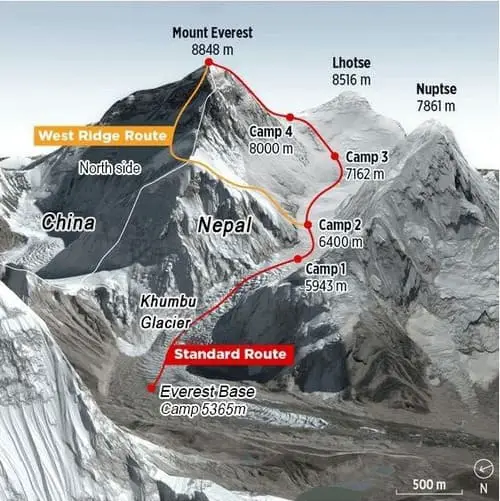

The expedition had dual objectives: firstly, to ascend the mountain via the established South Col route tracing the path established by New Zealand mountaineer Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, and secondly, to forge a new route via the West Ridge.

Hornbein, inspired by an aerial photograph of Everest from the Indian Air Force, identified a promising narrow couloir on the upper part of the mountain. The expedition faced resource allocation challenges between members committed to the distinct objectives, yet effective leadership maintained unity, culminating in success on both fronts.

Hornbein and Unsoeld’s 1963 Everest Ascent

In 1963, Tom Hornbein and his companions, Willi Unsoeld and Dick Emerson, undertook an ambitious ascent of Mount Everest as part of the American Everest Expedition. Their expedition colleagues, Jim Whittaker and Nawang Gombu Sherpa, had already achieved the summit on May 1, 1963. Distinguished by their audacity, Hornbein, Unsoeld, and Emerson set their sights on conquering the West Ridge. Previous ascents of Everest had solely been accomplished via the South Col and Southeast Ridge, or the North Col and Northeast Ridge.

Their strategy involved ascending the West Ridge and descending via the Southeast Ridge/South Col route, which would mark the pioneering traverse of an 8000-meter peak. On May 22, 1963, departing their final camp at 6:50 AM (Emerson remained at the high camp due to altitude sickness), the team commenced the ascent.

Despite facing slow progress, they remarkably reached the summit at 6:15 PM that same day. Although they found themselves significantly behind the anticipated schedule, the trio spent 20 minutes atop the summit before embarking on their descent.

However, challenges soon arose. Unsoeld, unfortunately, ran out of oxygen shortly after the descent began.

Shared Struggles of Everest Summiters in 1963

Around 9:30 AM, Tom Hornbein, Willi Unsoeld, Dick Emerson, along with fellow expedition members Barry Bishop and Lute Jerstad, encountered each other on the descent from Mount Everest’s summit.

Bishop and Jerstad had earlier reached the summit via the South Col route, but their energy was depleted, and their oxygen supplies were nearly exhausted. The group of five climbers decided to join forces for the descent, though their progress was notably slow.

As conditions became increasingly hazardous, the climbers made the cautious choice to halt their descent sometime after midnight, finding shelter and warmth by huddling together until 4:00 AM. They resumed their descent, crossing paths with fellow expedition members who were carrying spare oxygen tanks. Reaching their camp, they were met with distressing news—Unsoeld’s feet were severely frostbitten. Bishop and Jerstad also suffered from frostbite, resulting in the loss of toes for both Bishop and Unsoeld.

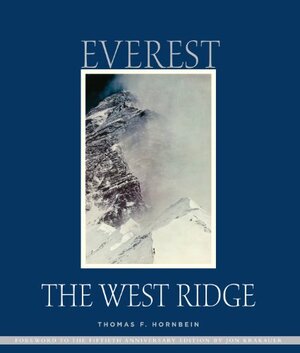

Hornbein documented this remarkable ascent in his book “Everest: The West Ridge,” (affiliate link!) a revered piece of mountaineering literature from that era:

“The night was overwhelming empty. The black silhouette of the Lhotse Mountain was lurking there, half to see, half to assume, and below of us. In general there was nothing – simply nothing. We hung in a timeless gap, pained by an intensive cold air – and had the idea not to be able to do anything but to shiver and to wait for the sun arising.”

– Tom Hornbein

A Life of Achievement: Tom Hornbein’s Legacy in Mountaineering and Beyond

Tom Hornbein left an indelible mark by coining the term “Hornbein Couloir,” denoting the steep gully he and Unsoeld ascended on the uppermost portion of the north wall of Everest. This remarkable achievement has been lauded by Jon Krakauer in his book “Into Thin Air.” Where Jon describes their ascent as one of the most extraordinary accomplishments in mountaineering history.

Following his Everest triumph, Tom Hornbein shifted his attention towards the field of medicine. Assuming the role of chair for the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Washington. Transitioning into academia, he contributed extensively to medical research, authoring more than a hundred journal articles and book chapters.

While his professional path led him away from the prominent realm of climbing, his enduring affinity for the mountains persisted. He engaged in exploration within the Cascades, close to his residence in Seattle, and also embarked on occasional international journeys.

In 2002, at the age of 72, Hornbein maintained an active role as both a Professor of Anesthesiology and an avid mountaineer. By 2006, he had relocated from Seattle to Estes Park, Colorado, where he resided alongside his wife, Kathy Mikesell Hornbein. The couple continued to indulge in regular climbing excursions within the Colorado Rockies.

Hornbein’s Awards:

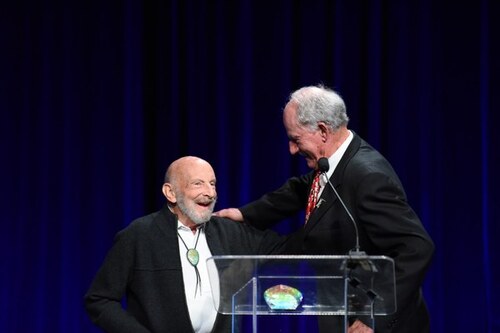

In 2018, Tom Hornbein was honored with The Mountaineers Lifetime Achievement award. An annual accolade bestowed upon individuals within The Mountaineers community who have made enduring contributions to the outdoor realm. Jim Whittaker, Tom’s climbing partner and lifelong friend, had the privilege of presenting him with the award.

Death of Tom Hornbein

Renowned for his accomplishments as a geologist, anesthesiologist, and high-altitude mountaineer, Tom Hornbeing peacefully passed away on May 6, 2023. In the early hours of the morning at his residence in Estes Park, Colorado. Recognized as a trailblazing pioneer in the climbing world, Tom left an indelible legacy. He reached the age of 92 before his passing.