The 1924 British Mount Everest expedition was the second expedition with the goal of being the first people to reach the top of Mount Everest. After two previous summit attempts by Edward Norton, two climbers named George Mallory and Andrew Irvine made the third attempt. However, during the quest for the summit they disappeared.

People have wondered whether the two reached the summit, sadly there is not enough conclusive information to say for sure. In 1999, Mallory’s body was found at a lower altitude, but it didn’t give a clear answer about whether they made it to the top.

This blog looks at The 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition, as well as George Mallory and Andrew Irvine’s last days alive.

British Climbers Quest for Mount Everest: Challenges and Exploration

In the early 1900s, the British tried to reach the North and South Poles but didn’t succeed. They wanted to regain national pride, so they started thinking about climbing the highest mountain on Earth, which they called the “third pole.”

The southern side of the mountain, which is the common route used today, was not accessible because Nepal didn’t allow Westerners to enter the country. Going to the north side was politically complicated, and it required the British-Indian government to negotiate with the Dalai Lama regime in Tibet to allow British expeditions.

One challenge of climbing the north side of Mount Everest was the limited time between winter and the start of the monsoon season. The journey from Darjeeling in India to Tibet involved crossing snowy mountain passes in the Kangchenjunga area. The explorers had to travel through the Arun River valley to reach the Rongbuk valley near the north face of Mount Everest. They used horses, donkeys, yaks, and local porters to transport their equipment.

The expeditions arrived at Mount Everest in late April and had only until June before the monsoon rains began. This gave them only six to eight weeks to acclimatize to the high altitude, set up camps, and make their summit attempts.

Planning and Preparing For The 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition

Before the 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition, there were two earlier expeditions. The first one in 1921, led by Harold Raeburn, explored a potential route along the entire northeast ridge. George Mallory later suggested a modified climb, starting from the north col and following the north and northeast ridges to reach the summit. This route appeared to be the easiest path to the top. They discovered access to the base of the north col via the East Rongbuk Glacier, which seemed to be the best option. During the 1922 expedition, they made several attempts on Mallory’s proposed route.

However, due to limited preparation time and financial constraints, there was no expedition in 1923. The Common Everest Committee faced financial difficulties after losing a significant amount of money in the bankruptcy of the Alliance Bank of Simla. As a result, the third expedition had to be postponed until 1924.

Similar to the previous expeditions, the 1924 expedition was planned, financed, and organized by members of the Royal Geographical Society, the Alpine Club, and Captain John Noel, who played a major role and acquired all photographic rights. The Mount Everest Committee adopted military strategies and involved some military personnel in the expedition.

A Shift in Roles and Oxygen Debate: Changes in Mountaineering on Everest

A significant change occurred in the role of porters during the 1924 expedition. The previous 1922 British expedition on Everest, recognized that some porters had the ability to climb to great heights and quickly learn mountaineering skills. This recognition led to a revised climbing strategy that involved increased participation of the porters.

This shift ultimately culminated in an important partnership between Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary, who together achieved the first known ascent during the 1953 British Everest Expedition. Over time, there was a gradual reversal of the traditional “Sahib-Porter” system from earlier expeditions, resulting in a situation where Sherpa “porters” became the highly skilled mountaineering professionals, while Western climbers often assumed the role of clients with less expertise.

Similar to the 1922 expedition, the 1924 expedition also brought bottled oxygen to the mountain. Although there were improvements in the oxygen equipment during the intervening years, it still had reliability issues. Moreover, there was ongoing debate and uncertainty about whether to use this assistance at all. This marked the beginning of a discussion that continues to this day: the “sporting” arguments favor climbing Everest “by fair means” without relying on technical measures that significantly mitigate the effects of high altitude.

Leadership, Team Selection, and Technical Expertise:

The 1924 expedition was led by the same leader as the 1922 expedition, General Charles G. Bruce. His responsibilities included managing equipment and supplies, hiring porters, and determining the route to the mountain.

Choosing the climbers for the expedition was not an easy task. The aftermath of World War I had created a shortage of strong young men. George Mallory, Howard Somervell, Edward “Teddy” Norton, and Geoffrey Bruce were all part of the mission once again. George Ingle Finch, who had set a height record in 1922, was considered for the team but ultimately not included. The committee’s decision was influenced by factors such as his divorce and accepting money for lectures.

The influential Secretary of the committee, Arthur Hinks, made it clear that having an Australian as the first to reach Everest was not acceptable. The British wanted the climb to serve as an example of British spirit to boost morale. Mallory initially refused to participate without Finch, but he changed his mind after personal persuasion from the British royal family, as requested by Hinks.

The new additions to the climbing team included Noel Odell, Bentley Beetham, and John de Vars Hazard. Andrew “Sandy” Irvine, an engineering student whom Odell knew from a previous expedition, was considered an “experiment” for the team, representing the inclusion of young blood on the slopes of Mount Everest. Irvine’s technical and mechanical expertise allowed him to improve the oxygen equipment, reduce its weight, and perform various repairs to it and other expedition equipment.

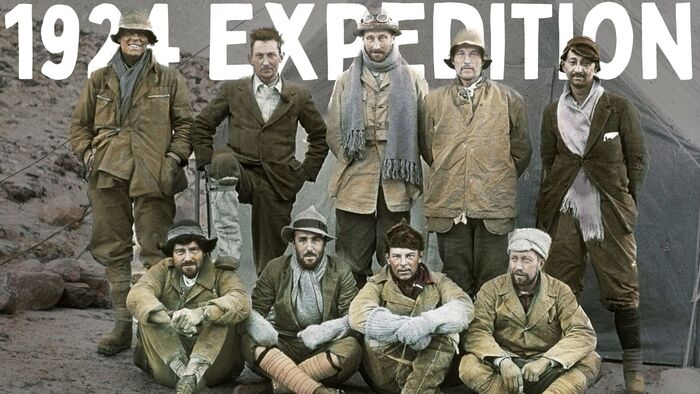

The complete expedition team included 60 porters and the following individuals:

| Name | Role | Profession |

|---|---|---|

| Charles G. Bruce | Head of expedition | Soldier (Officer, Brigadier-General) |

| Edward F. Norton | Deputy head of expedition | Soldier (Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel) |

| George Mallory | Climber | Teacher |

| Bentley Beetham | Climber | Teacher |

| Geoffrey Bruce | Climber | Engineer |

| John de Vars Hazard | Climber | Medical Doctor & Soldier (Officer, Major) |

| R.W.G. Hingston | Expedition Doctor | Medical Doctor & Soldier (Officer, Major) |

| Andrew Irvine | Climber | Engineering Student |

| John B.L. Noel | Photographer/ Videographer | Soldier (Officer, Captain) |

| Noel E. Odell | Climber | Geologist |

| E.O. Shebbeare | Transportation Officer/ Interpreter | Forester |

| Dr. T. Howard Somervell | Climber | Medical Doctor |

Accessing the North Side and Various Climbing Routes on Mount Everest

During the time before World War II, foreigners were not allowed to enter the kingdom of Nepal, so British expeditions could only approach Mount Everest from the north side. In 1921, Mallory identified a potential route from the North Col to the summit. This path involved traversing the East Rongbuk Glacier to reach the North Col, and then ascending the windy ridges known as the North Ridge and Northeast Ridge, which appeared to offer a practical route to the top. However, an imposing challenge awaited on the Northeast Ridge—a steep cliff called the Second Step at 8,605 meters (28,230 ft).

The Chinese were the first to ascend to the summit following the Northeast Ridge route in 1960. Prior to that, British climbers since 1922 had attempted a different approach, descending significantly down the ridge, crossing the massive north face to reach the Great Couloir (later known as the “Norton Couloir”).

They then climbed along the border of the couloir and aimed for the summit pyramid. This route proved unsuccessful until Reinhold Messner completed a solo ascent along this path in 1980. The exact route taken by Mallory and Irvine is unknown.

They may have either used the natural Norton/Harris route, cutting diagonally through the Yellow Band ledges to reach the Northeast Ridge, or possibly followed the North Ridge directly to the Northeast Ridge. Whether either of them reached the summit remains a mystery.

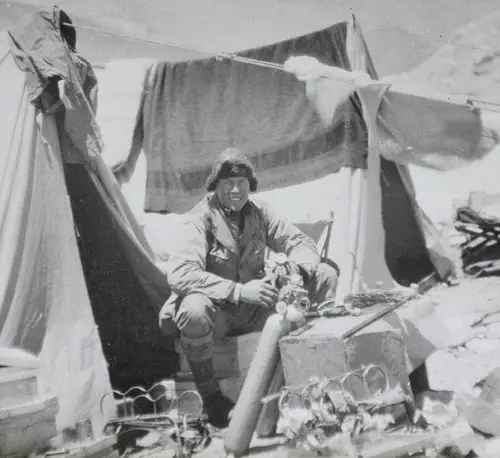

(The image above is captioned as “George Mallory Climbing Like a Spider”.)

Setting up Camps and Challenging Weather Conditions

The expedition had pre-planned locations of the high camps. Camp I, situated at 5,400 meters, served as an intermediate camp at the entrance of the East Rongbuk Glacier. Camp II, around 6,000 meters, was another intermediate camp halfway to Camp III, which was the advanced base camp located at 6,400 meters, about 1 kilometer from the icy slopes leading to the North Col.

Porters were employed to transport supplies from the base camp to the advanced base camp. These porters were paid around one shilling per day. By the end of April, the camp positions were expanded, and this work was completed in the first week of May.

Due to a snowstorm, further climbing activities were delayed. As the weather started to improve, Norton, Mallory, Somervell, and Odell reached Camp III on May 19. The next day, they began fixing ropes on the icy slopes leading to the North Col. On May 21, they established Camp IV at an elevation of 7,000 meters.

Unfortunately, the weather conditions worsened again. John de Vars Hazard remained in Camp IV on the North Col with twelve porters and limited food supplies. Eventually, Hazard managed to descend, but only eight porters accompanied him. The other four porters, who fell ill, were rescued by Norton, Mallory, and Somervell. The entire expedition then returned to Camp I. There, fifteen porters who had demonstrated exceptional strength and climbing abilities were selected as the so-called “tigers.”

Summit Attempts and Challenges:

The summit attempts were organized in a planned sequence. Mallory and Bruce were scheduled for the first attempt, followed by Somervell and Norton. Odell and Irvine would provide support from Camp IV on the North Col, while Hazard would support from Camp III. These supporting team members would also serve as reserve teams for a potential third attempt. The first and second attempts were planned to be done without the use of bottled oxygen.

1. First Attempt: Mallory and Bruce

On June 1, 1924, Mallory and Bruce embarked on their first summit attempt from the North Col, accompanied by nine porters known as the “tigers.” Camp IV was located in a relatively sheltered area, about 50 meters below the edge of the North Col. However, once they left the protection of the ice walls, they were exposed to harsh, icy winds blowing across the North Face. Before they could establish Camp V at 7,681 meters, four porters decided to abandon their loads and turn back.

While Mallory set up the tent platforms, Bruce and one porter retrieved the abandoned supplies. The following day, three more porters expressed their reluctance to climb higher, leading to the decision to abort the attempt without setting up Camp VI as originally planned at 8,170 meters. On their descent to Camp IV, the first summit team encountered Norton and Somervell, who had just begun their own attempt.

2. Second Attempt: Norton and Somervell

On June 2, Norton and Somervell began the second summit attempt with the support of six porters. They were surprised to see Mallory and Bruce descending early and wondered if their own porters would also refuse to continue beyond Camp V. Two porters were indeed sent back to Camp IV, but the remaining four porters and the two climbers spent the night at Camp V. The following day, three porters brought the necessary materials to establish Camp VI at 8,170 meters in a small niche. The porters were then sent back to Camp IV on the North Col.

On June 4, Norton and Somervell started their summit bid. The weather was favorable.

After ascending over 200 meters along the North Ridge, they decided to traverse the North Face diagonally. However, the lack of supplemental oxygen and the effects of altitude forced them to take frequent rest breaks.

Around noon, Somervell reached his limit and could no longer ascend. Norton continued alone and made his way to the deep gulley known as the “Norton Couloir” or “Great Couloir,” which leads to the eastern foot of the summit pyramid. During this solo climb, Somervell captured a remarkable photograph of Norton near his high point of 8,572.8 meters, where he encountered steep, icy terrain. Norton’s altitude set a confirmed world record that remained unbroken for 28 years until the 1952 Swiss Mount Everest Expedition (one of many missions to Everest, see our entire timeline of expeditions on Everest.)

With the summit only 280 meters above him, Norton decided to turn back due to increasing terrain difficulty, time constraints, and doubts about his remaining strength. He reunited with Somervell at 2 pm, and they began their descent.

While following Norton, Somervell experienced a severe throat blockage, causing him to sit down, preparing for the worst. In a desperate final attempt, he compressed his lungs with his arms and managed to dislodge the blockage, described as the lining of his throat. He then continued following Norton, who was unaware of Somervell’s life-threatening episode.

They reached Camp IV in the darkness at 9:30 pm, using electric torches for light. Mallory offered them oxygen bottles, but their priority was to drink water. During the night, Mallory discussed his plan with Norton to make a final attempt with Andrew Irvine and utilize oxygen.

Norton suffered from intense eye pain, rendering him snow blind by morning. He remained blinded for sixty hours and stayed in Camp IV on June 5 to coordinate the porters from his tent. On June 6, Norton was carried down to Camp III (Advanced Base Camp) by a group of six porters who took turns carrying him.

3. Third Attempt: Mallory and Irvine

On June 5, Mallory and Irvine were at Camp IV. Mallory discussed his decision to choose Sandy Irvine as his climbing partner with Norton. Despite Irvine’s lack of high-altitude climbing experience, Norton, as the expedition leader, supported Mallory’s plan due to Irvine’s practical skills with the oxygen equipment. Mallory and Irvine had developed a strong friendship during their journey to India, and Mallory considered the young Irvine to be physically strong.

On June 6, Mallory and Irvine set off for Camp V at 8:40 am accompanied by eight porters. They carried modified oxygen apparatus with two cylinders and a day’s ration of food. Odell captured a photograph of them, which would become the last close-up picture taken of the two climbers alive. Around 5 pm that evening, four porters returned from Camp V with a note from Mallory stating, “There is no wind here, and things look hopeful.”

On June 7, Odell and Nema, and a porter, went to Camp V to support the summit team. During the journey, Odell found an abandoned oxygen-breathing set on the ridge but discovered it was missing the mouthpiece. He carried it to Camp V in the hope of finding an extra mouthpiece but was unsuccessful. Shortly after Odell’s arrival at Camp V, the remaining four porters who had assisted Mallory and Irvine returned from Camp VI. They delivered a message to Odell from Mallory, expressing the plan to start early the next day and indicating specific landmarks to look out for.

John Noel, stationed at the photographic lookout point above Camp III, along with two porters, kept a lookout for the climbers on June 8 from 8 am. They took turns using a telescope, ready to activate the camera if any sign of the climbers was spotted. However, they did not see anyone, and by 10 am, the view was obscured by clouds.

Mallory and Irvine’s Last Sighting During the 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition:

On the morning of June 8, Odell woke up at 6 am, reporting calm winds and a restful night of sleep. At 8 am, he began an ascent to Camp VI to conduct geological studies and provide support to Mallory and Irvine. However, misty conditions limited his visibility of the Northeast Ridge, the route Mallory and Irvine intended to take. At an altitude of 7,900 meters, Odell climbed over a small outcropping. At 12:50 pm, the mist suddenly cleared, and Odell noted in his diary that he saw Mallory and Irvine on the ridge, nearing the base of the final pyramid.

In a subsequent report, Odell clarified that he observed the summit ridge and final pyramid of Everest when the weather cleared. He spotted a tiny black dot, Mallory, moving on a small snow crest beneath a rock-step on the ridge, and there appeared to be another dot, Irvine, moving towards the first one. However, Odell couldn’t be certain if the second dot also reached the crest of the ridge.

Initially, Odell believed that the climbers had reached the base of the Second Step. He grew concerned when Mallory and Irvine seemed to be five hours behind their planned schedule. After this sighting, Odell continued his journey to Camp VI, where he found the tent in disarray. At 2 pm, a heavy snow squall began, prompting Odell to venture out in an attempt to signal Mallory and Irvine, whom he expected to be descending by that time. Whistling and shouting, Odell tried to guide them back to the tent but had to give up due to the extreme cold. Odell remained in Camp VI until the squall subsided at 4 pm. He scanned the mountain for any signs of Mallory and Irvine but found none.

‘No Trace Can Be Found, Given Up Hope, Awaiting Orders’

As the single tent at Camp VI could only accommodate two people, Mallory had advised Odell to leave and return to Camp IV on the North Col. Odell left Camp VI at 4:30 pm and arrived at Camp IV by 6:45 pm. Since there had been no sign of Mallory and Irvine that day or the following day, Odell, accompanied by two porters, ascended the mountain once again.

They reached Camp V and stayed there overnight. The next day, Odell proceeded alone to Camp VI, finding it unchanged. He climbed up to around 8,200 meters but saw no trace of the two missing climbers. In Camp VI, Odell arranged six blankets in a cross on the snow, indicating “No trace can be found, Given up hope, Awaiting orders” to the advanced base camp. Odell descended to Camp IV. On the morning of June 11, the team started their descent, navigating the icy slopes of the North Col, officially ending the expedition.

Legacy and Controversies: Reflections on the 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition:

In memory of the climbers who lost their lives on Mount Everest in the 1920s, a memorial cairn was erected by the expedition members. Mallory and Irvine were hailed as national heroes, with Magdalene College at the University of Cambridge and the University of Oxford each dedicating memorial stones to honor their respective climbers. A ceremony was held at St Paul’s Cathedral, attended by King George V, dignitaries, and the families and friends of the climbers.

The expedition’s official film, The Epic of Everest, produced by John Noel, sparked a diplomatic controversy known as the Affair of the Dancing Lamas. Monks from Tibet were secretly brought to perform before each screening of the film, which greatly offended the Tibetan authorities. As a result, access for further expeditions was denied by the Dalai Lama until 1933, partly due to this incident and unauthorized activities during the expedition.

Odell’s Sighting of Mallory and Irvine:

Opinions within the climbing community questioned the location where Odell claimed to have seen Mallory and Irvine. Many believed that the challenging Second Step could not have been climbed in the short time Odell observed them. Odell and Norton, however, believed they had reached the summit, with Odell expressing this belief to the newspapers. The expedition report, supported by prominent mountaineer Martin Conway, also suggested that the summit had been reached based on their position and Mallory’s skills.

Under pressure, Odell changed his account of the sighting multiple times. Most climbers believe he saw them on the easier First Step. Inconsistencies arose regarding the weather conditions he described. A recent theory proposes that Mallory and Irvine were cresting the First Step on their descent, capturing photographs of the remaining route. The exact location of their sighting remains uncertain, and Odell himself admitted uncertainty before his death. Conrad Anker, who found the famous dead body on Mount Everest, of George Mallory, suggests they were likely in the vicinity of the First Step, considering the challenging nature of the climb.

Odell’s Discoveries and Subsequent Expeditions:

Odell found significant evidence related to Mallory and Irvine climb in camps V and VI, including Mallory’s compass, oxygen bottles, and spare parts. The presence of these items suggests possible issues with the oxygen equipment that could have caused a delayed start. The discovery of a working hand-generator electric lamp in the tent by the Ruttledge expedition years later adds to the mystery.

In 1933, Percy Wyn-Harris found Irvine’s ice axe east of the First Step, suggesting a fatal accident or a deliberate abandonment due to a slip or the need for free hands. In 1975, a Chinese mountaineer reported seeing an “English dead” at 8,100 meters, sparking further interest. A 1999 search expedition discovered Mallory’s body at 8,159 meters, showing signs of a fall and injuries that made a walking descent impossible. The lack of oxygen equipment near the body and missing snow goggles raised questions about their progress and the possibility of a successful summit climb. The fate of Irvine and confirmation of reaching the summit remain unknown due to the absence of conclusive evidence.

Speculation on Mallory and Irvine’s First Ascent:

There have been claims and rumors suggesting that Mallory and Irvine were the first to reach the summit of Mount Everest in 1924. Some argue against this, claiming that their clothing was of poor quality and the accounts of Odell were not inline with a summit. However, a recreation of Mallory’s clothing by Graham Hoyland in 2006 proved it to be functional and comfortable at high altitudes.

The details of Odell’s sighting are of great interest. Analysis of his description and current knowledge suggests that Mallory’s reported speed in surmounting the Second Step is unlikely. The wall cannot be climbed as quickly as described. Odell’s mention of the summit pyramid contradicts a location at the First Step, and it is unlikely they could have reached the Third Step by the given time. One theory suggests that Odell may have mistaken birds for climbers, a phenomenon observed by Eric Shipton in 1933.

Moreover, the long distance from high camp VI to the summit makes it unlikely to reach before dark when starting in daylight. It wasn’t until 1990 that Ed Viesturs accomplished a similar feat, and he had prior knowledge of the route. Mallory and Irvine ventured into unknown territory. Additionally, Irvine’s lack of experience suggests that Mallory wouldn’t have endangered his friend or pursued the summit without careful risk assessment.

The exact circumstances of their demise remain unknown, although Mallory’s body was discovered in 1999, Irvine’s has never been seen.

The Legacy of the 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition:

The 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition remains an enduring chapter in mountaineering history. While the ultimate fate of George Mallory and Andrew Irvine on their summit bid remains a mystery, their courage and determination continue to inspire generations of climbers.

The expedition’s pioneering spirit, despite the challenges and limitations of the time, laid the groundwork for future endeavors on the world’s highest peak. The 1924 British Mount Everest Expedition’s legacy lives on, and until Irvine’s body or his camera are recovered, we may never know if they actually made it to the summit of Everest or not.