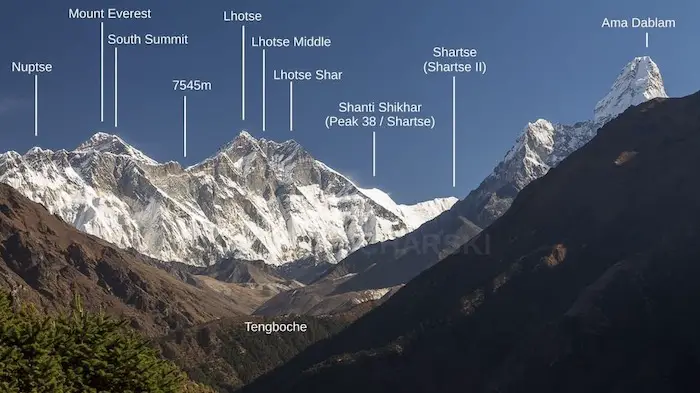

Mount Everest, known as Sagarmāthā in Nepali and Chomolungma in Tibetan, is the tallest peak on Earth above sea level. Situated within the Mahalangur Himal sub-range of the Himalayas, the summit serves as the dividing point for the China-Nepal border. Its elevation, measured as 8,848.86 meters (29,031 feet and 8.5 inches), was jointly reaffirmed by Chinese and Nepali authorities in 2020.

The mountain features two principal climbing routes. The “standard route” from the southeast in Nepal, and the northern approach from Tibet. Although the standard route doesn’t impose significant technical climbing obstacles, its risks include altitude sickness, adverse weather conditions, and potential dangers arising from avalanches and the treacherous Khumbu Icefall. Tragically, as of January 2023, the mountain has claimed the lives of over 300 individuals.

The inaugural endeavors to conquer Everest’s summit were undertaken by British mountaineers. Given Nepal’s restriction on foreign entry during that period, the British directed multiple efforts toward the north ridge route from Tibet. Following the initial British reconnaissance expedition in 1921, which attained an altitude of 7,000 meters (22,970 feet) at the North Col, the 1922 expedition progressed along the north ridge route to an elevation of 8,320 meters (27,300 feet). Marking the first instance of a human surpassing the 8,000-meter (26,247-foot) mark.

The first ascent of Everest was achieved in 1953 by Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary, following the southeast route. Subsequently, the Chinese mountaineering trio of Wang Fuzhou, Gonpo, and Qu Yinhua completed the first recorded ascent from the north ridge on 25 May 1960.

Where did the Name Mount Everest Come from?

Everest carries the Tibetan designation of Qomolangma (signifying “Holy Mother”). This title was initially inscribed in a Chinese transcription within the 1721 Kangxi Atlas during the rule of Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty. Subsequently, it appeared as Tchoumour Lancma on a 1733 map created by the French geographer D’Anville. A peice of work that drew signifcantly from the Kangxi Atlas.

In the early 1960s, the Nepali government introduced the Nepali name Sagarmāthā or Sagar-Matha (सगर-माथा, signifying “goddess of the sky”). This appellation translates to “the Head in the Great Blue Sky” and derives from सगर (sagar), denoting “sky,” and माथा (māthā), meaning “head.”

The recognized Chinese transcription stands as 珠穆朗玛峰, with its pinyin representation being Zhūmùlǎngmǎ Fēng. Although alternative Chinese names, such as Shèngmǔ Fēng (translating to “Holy Mother Peak”), were once employed, these designations were largely replaced following a decree from China’s Ministry of Internal Affairs in May 1952. Which effectively established a singular name as the official reference.

During 1849, the British survey team aimed to uphold local names whenever feasible. However, in this pursuit, Andrew Waugh, the British Surveyor General of India, encountered difficulties in locating a commonly used local name. Waugh’s reasoning stemmed from the presence of numerous local names, making it difficult to elevate one above the rest. Consequently, he opted to rename Peak XV after his predecessor, British surveyor Sir George Everest. This decision faced opposition from Everest himself. He conveyed to the Royal Geographical Society in 1857 that the name “Everest” couldn’t be written in Hindi nor articulated by “natives of India.” Despite Everest’s dissent, Waugh’s proposed nomenclature prevailed. And in 1865, the Royal Geographical Society officially endorsed Mount Everest as the name for the world’s highest peak.

Original and Additional Names of Everest:

- Peak XV (British Empire’s Survey)

- Peak b – John Armstrong named Everest this during the initial Great Trigonometrical Survey of India

- Old Darjeeling name: “Deodungha”

- “Gauri Shankar” or “Gaurisankar”; in modern times the name is used for a different peak about 30 miles (48 kilometres) away. But it was used occasionally until about 1900

- Sagarmāthā or Sagar-Matha (सगर-माथा) – Nepali name for Everest

- Qomolangma (signifying “Holy Mother”) – Tibetan name for Everest

- 珠穆朗玛峰 – Zhūmùlǎngmǎ Fēng – Chinese name for Everest

Where is Mount Everest?

The location of Mount Everest, situated in the Himalayas, is at the border between Nepal and the autonomous region of Tibet in China. This iconic summit’s geographic coordinates are approximately 27.9881°N latitude and 86.9250°E longitude.

Everest is a colossal part of the landscape and a significant focal point of the Earth’s topography. It is nestled within the Khumbu region of Nepal on its southern side and the Tingri County of Tibet on the northern side. The surrounding terrain is characterized by rugged peaks, deep valleys, and ancient glaciers, showcasing the breathtaking beauty of the Himalayas.

Scientific Surveys of Mount Everest:

Scientific surveys of Mt. Everest has taken place during the last three centuries. The findings and details of each century can be seen in their respective sections below.

1. 19th Century Surveys:

In 1802, the British initiated the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India. Aimed at determining the positions, elevations, and designations of the planet’s tallest mountains. Commencing from the southern point of India, teams of surveyors progressed northward, employing colossal theodolites, each weighing 500 kg (1,100 lb) and necessitating a crew of 12 men for transport, to accurately determine the height. By the 1830s, they had reached the outskirts of the Himalayas. However, Nepal’s suspicions about their intentions resulted in the country’s refusal to grant the British access on multiple attempts.

Faced with this challenge, the British persevered in their efforts by conducting observations from Terai, a region south of Nepal that runs parallel to the Himalayan range. Terai posed formidable challenges due to incessant rainfall and the prevalence of malaria. Tragically, three survey officers succumbed to malaria, and two others had to retire due to deteriorating health conditions.

After setbacks, the British resumed their survey in 1847 and conducted observations of the Himalayan summits from distant vantage points situated about 240 km (150 mi) away. In November 1847, Andrew Scott Waugh, the British Surveyor General of India, conducted several observations from the Sawajpore station positioned at the eastern terminus of the Himalayas. At that time, Kangchenjunga was regarded as the world’s highest peak. Amid his observations, Waugh detected a peak situated beyond Kangchenjunga, roughly 230 km (140 mi) away. John Armstrong, one of Waugh’s subordinates, also sighted the peak from a more westerly location and denoted it as peak “b.” Waugh subsequently reported that the observations suggested peak “b” exceeded Kangchenjunga in elevation. Yet, considering the considerable distance of the observations, closer and more exact measurements were necessary for verification.

By 1852, stationed at the survey’s headquarters in Dehradun, Radhanath Sikdar, an Indian mathematician and surveyor from Bengal, achieved a significant breakthrough by identifying Everest as the planet’s highest peak. He accomplished this feat through intricate trigonometric calculations founded on Nicolson’s measurements. However, an official proclamation confirming Peak XV’s status as the highest peak was deferred for several years, as the calculations underwent rigorous verification. Commencing work on Nicolson’s data in 1854, Waugh and his team devoted nearly two years to refining the figures.

In March 1856, Waugh ultimately disclosed his findings in a letter to his deputy in Calcutta. In this announcement, Kangchenjunga’s height was established at 8,582 m (28,156 ft), while Peak XV was accorded an elevation of 8,840 m (29,002 ft). Waugh concluded that Peak XV was “very likely the highest in the world.”

Although Peak XV’s true elevation, in feet, was precisely 29,000 ft (8,839.2 m), it was publicly stated as 29,002 ft (8,839.8 m) to avoid the misconception that an elevation of 29,000 feet (8,839.2 m) was merely a rounded approximation. As a playful nod, Waugh is occasionally credited with being “the first person to place two feet on the summit of Mount Everest.”

2. 20th-Century Surveys of Everest:

Between 1952 and 1954, utilizing triangulation techniques, the Survey of India determined Everest’s height to be 8,847.73 m (29,028 ft). Subsequently, in 1975, a Chinese measurement affirmed this elevation at 8,848.13 m (29,029.30 ft). Notably, in both instances, the measurements pertained to the snow-covered summit rather than the underlying rock formation. The height of 8,848 m (29,029 ft) was formally accepted by both Nepal and China.

In 1955, Erwin Schneider generated an intricate photogrammetric map (at a scale of 1:50,000) of the Khumbu region, encompassing the southern face of Mount Everest, as part of the 1955 International Himalayan Expedition, which also aimed at conquering Lhotse.

During the late 1980s, under the guidance of Bradford Washburn, an even more exhaustive topographic map of the Everest vicinity was crafted, employing extensive aerial photography.

In May 1999, an American Everest expedition led by Bradford Washburn deployed a GPS unit to anchor into the highest bedrock. Through this device, they obtained a rock head elevation of 8,850 m (29,035 ft), with a slightly higher snow/ice elevation by 1 m (3 ft). While this figure gained widespread acceptance, it was never recognized by Nepal.

3. 21st-Century Surveys of Everest:

On October 9, 2005, following an extended period of measurement and computation, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping unveiled Everest’s height as 8,844.43 m (29,017.16 ft) with a precision level of ±0.21 m (8.3 in).

This announcement asserted that this measurement represented the most meticulous and accurate determination up until that point. The reported elevation pertains to the highest rocky peak, not accounting for the covering of snow and ice. The Chinese team’s measurements indicated a depth of snow and ice at 3.5 m (11 ft), harmonizing with a net elevation of 8,848 m (29,029 ft). A debate emerged between China and Nepal regarding whether the official elevation should encompass the rocky height (8,844 m, according to China) or the snowy elevation (8,848 m, according to Nepal).

By 2010, both nations reached consensus, designating Everest’s height as 8,848 m, and Nepal acknowledging China’s assertion that the rocky elevation of Everest is 8,844 m. On December 8, 2020, a joint announcement from both countries established the new official height of Everest at 8,848.86 meters (29,031.7 ft).

Comparing Mount Everest’s Height With Other Mountain Peaks:

The summit of Everest marks the highest point above sea level on Earth’s surface. However, there are instances where other mountains are occasionally regarded as the “tallest mountains on Earth.” For instance, Mauna Kea in Hawaii claims this distinction when measured from its base on the ocean floor. From base to summit it’s height is 10,200 m (33,464.6 ft), yet it only reaches an elevation of 4,205 m (13,796 ft) above sea level.

Similarly, Denali (Mount McKinley), situated in Alaska, surpasses Everest when measured from its base to summit. Despite an elevation of just 6,190 m (20,308 ft) above sea level, Denali is positioned on a gradually inclining plain that stretches from 300 to 900 m (980 to 2,950 ft) in elevation, yielding an elevation range of 5,300 to 5,900 m (17,400 to 19,400 ft) above its base; commonly cited estimates hover around 5,600 m (18,400 ft).

By contrast, Everest’s base elevations vary from 4,200 m (13,800 ft) on its southern face to 5,200 m (17,100 ft) on the Tibetan Plateau, resulting in an elevation range of 3,650 to 4,650 m (11,980 to 15,260 ft) above its base, much smaller than Denali.

The summit of Chimborazo in Ecuador holds the distinction of being 2.17 km (1.34 miles) further from Earth’s center (6,384.4 km, 3,967.1 mi) compared to Everest’s summit (6,382.3 km, 3,965.8 mi) due to the Earth’s equatorial bulge. This is noteworthy despite Chimborazo’s peak rising to an elevation of 6,268 m (20,564.3 ft) above sea level, as opposed to Mount Everest’s elevation of 8,848 m.

Geology of Mt. Everest:

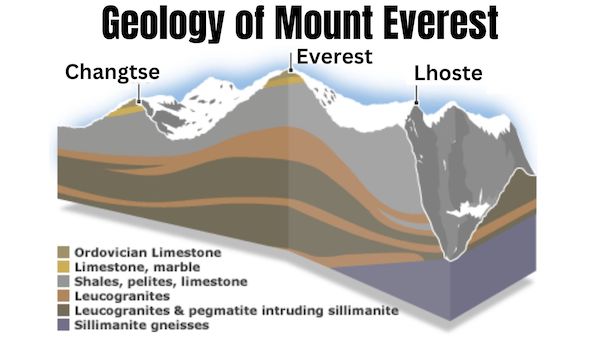

Mount Everest’s rock composition has been categorized into three distinct formations. These formations are demarcated by low-angle faults, known as detachments, which have caused them to shift southward over one another. Progressing from Everest’s peak to its base, these rock units encompass the Qomolangma Formation, the North Col Formation, and the Rongbuk Formation.

1. The Qomolangma Formation:

Also recognized as the Jolmo Lungama Formation, it stretches from the summit to the upper reaches of the Yellow Band, situated approximately 8,600 m (28,200 ft) above sea level. This formation comprises grayish to dark gray or white layers of Ordovician limestone, arranged in parallel laminated and bedded structures, interspersed with subordinate strata of recrystallized dolomite containing argillaceous laminae and siltstone.

A prominent thrombolite bed with a white weathering profile, measuring 60 m (200 ft) in thickness, constitutes the base of the “Third Step” and the foundation of Everest’s summit pyramid. Emerging around 70 m (230 ft) below Everest’s peak, this stratum comprises sediments captured, bonded, and solidified by micro-organisms’ biofilms, predominantly cyanobacteria, within shallow marine waters. The Qomolangma Formation is intersected by various high-angle faults that culminate at the low-angle normal fault, termed the Qomolangma Detachment.

2. North Col Formation:

Between 7,000 and 8,600 m (23,000 and 28,200 ft), the predominant rock formation on Mount Everest is known as the North Col Formation, with the upper portion from 8,200 to 8,600 m (26,900 to 28,200 ft) forming the Yellow Band. Comprising this layer are alternating strata of Middle Cambrian diopside-epidote-bearing marble, which weathers to a distinctive yellowish-brown hue, and muscovite-biotite phyllite and semischist. Examination of marble samples taken from around 8,300 m (27,200 ft) revealed that they contained up to five percent remains of recrystallized crinoid ossicles.

The lower section of the North Col Formation, visible between 7,000 to 8,200 m (23,000 to 26,900 ft) on Everest, comprises layered and altered schist, phyllite, and minor marble. From 7,600 to 8,200 m (24,900 to 26,900 ft), the North Col Formation primarily consists of biotite-quartz phyllite and chlorite-biotite phyllite interspersed with lesser amounts of biotite-sericite-quartz schist. Ranging between 7,000 and 7,600 m (23,000 and 24,900 ft), the lower portion of the North Col Formation encompasses biotite-quartz schist interspersed with epidote-quartz schist, biotite-calcite-quartz schist, and thin layers of quartzose marble. These metamorphic rocks appear to have originated from the transformation of Middle to Early Cambrian deep-sea flysch composed of interbedded materials such as mudstone, shale, clayey sandstone, calcareous sandstone, graywacke, and sandy limestone.

3. Rongbuk Formation

Beneath the 7,000 m (23,000 ft) mark, the Rongbuk Formation underlies the North Col Formation, constituting the base of Mount Everest. It comprises schist and gneiss with a sillimanite-K-feldspar grade, penetrated by numerous sills and dikes of leucogranite, ranging in thickness from 1 cm to 1,500 m (0.4 in to 4,900 ft). These leucogranites are part of a group of Late Oligocene–Miocene intrusive rocks collectively known as the Higher Himalayan leucogranite. Their formation stems from the partial melting of Paleoproterozoic to Ordovician high-grade metasedimentary rocks within the Higher Himalayan Sequence, occurring around 20 to 24 million years ago during the subduction of the Indian Plate.

Mount Everest comprises sedimentary and metamorphic rock formations that have undergone southward faulting over the continental crust, predominantly consisting of Archean granulites within the Indian Plate, during the Cenozoic collision between India and Asia. Present interpretations suggest that the Qomolangma and North Col formations encompass marine sediments that collected along the continental shelf of India’s northern passive continental margin prior to its collision with Asia.

As for the Rongbuk Formation, it is a succession of high-grade metamorphic and granitic rocks that originated from the transformation of high-grade metasedimentary rocks. These rocks experienced downward thrust and northward movement during the collision of India with Asia, encountering heating, metamorphism, and partial melting at depths exceeding 15 to 20 kilometers (9.3 to 12.4 miles) beneath sea level. Subsequently, they were propelled upwards to the surface through thrusting southward between two major detachment zones. The Himalayas are undergoing an ascent of approximately 4 millimeters per year.

Everest Becomes a IUGS Geological Heritage Site in 2022:

Regarding the acknowledgment of the “most elevated rock formations globally” as containing fossil-rich marine limestone, the Ordovician Rocks of Everest were incorporated by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) in its compilation of 100 geological heritage sites worldwide. This list was made public in October 2022.

The organization’s criteria characterize an IUGS Geological Heritage Site as “a significant location featuring geological components and/or processes of global scientific importance, serving as a reference, and/or making a considerable contribution to the advancement of geological sciences throughout history.”

Everest’s Flora and Fauna:

In terms of vegetation, a moss is known to thrive at an elevation of 6,480 meters (21,260 ft) on the mountain, possibly making it the highest altitude plant species documented. An alpine cushion plant named Arenaria has been observed growing below 5,500 meters (18,000 ft) in the vicinity. A study based on satellite data spanning from 1993 to 2018 has revealed an expansion of vegetation in the Everest region, with plant life emerging in areas previously deemed barren.

Euophrys Omnisuperstes, a small black jumping spider, has been discovered at elevations reaching 6,700 meters (22,000 ft), potentially making it the highest non-microscopic permanent resident known on Earth. Within Everest’s base camp, the jumping spider Euophrys Everestensis can be found, lurking within crevices and possibly subsisting on frozen insects carried there by the wind.

Bird species like the bar-headed goose have been observed flying at higher elevations on the mountain. The chough, for instance, has been sighted as high as the South Col at 7,920 meters (25,980 ft). Yellow-billed choughs have even been observed at 7,900 meters (26,000 ft), and migratory bar-headed geese traverse the Himalayas. In 1953, George Lowe, a member of the Tenzing and Hillary expedition, reported seeing bar-headed geese flying over Everest’s summit.

When it comes to animals on Mount Everest, yaks are frequently seen. Commonly employed to transport equipment for Mount Everest climbs, these animals can carry loads of up to 100 kg (220 pounds). Other inhabitants of the region include the Himalayan tahr, which is occasionally preyed upon by the snow leopard. The Himalayan black bear can be found at altitudes of up to around 4,300 meters (14,000 ft), and the red panda is also present in the area.

Climate of Everest:

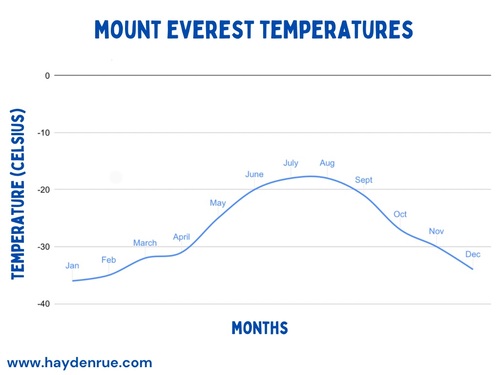

Mount Everest’s climate is classified as an ice cap climate with every month’s temperature averaging well below freezing. Temperatures on Mount Everest can get as low as -36 °C in January with temps staying well below 0°C throughout the year on the mountain.

In the table below, the temperature listed represents the average minimum recorded temperature for each respective month. This means that, on an annual average, the lowest temperature recorded in July would be -18 degrees Celsius, while the lowest temperature recorded in January would be -36 degrees Celsius.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −36(−33) | −35(−31) | −32(−26) | −31(−24) | −25(−13) | −20(−4) | −18(0) | −18(0) | −21(−6) | −27(−17) | −30(−22) | −34(−29) | −36(−33) |

Effects of Climate Change on Everest:

Nepal’s Everest base camp is situated alongside the Khumbu Glacier, which is experiencing rapid thinning and destabilization due to the effects of climate change. Consequently, the glacier’s condition has become hazardous for climbers.

Following the recommendations of a committee established by Nepal’s government to facilitate and oversee mountaineering activities in the Everest region, Taranath Adhikari, the director general of Nepal’s tourism department, disclosed plans to relocate the base camp to a lower altitude. Such a move would result in a greater distance between the base camp and Camp 1 for climbers.

Nevertheless, the existing base camp remains functional and will continue to serve its purpose for the foreseeable future. Officials anticipate that the relocation could take place by 2024. However, the relocation of the base camp has not garnished much support in the mountaineering community.

Meteorology of Mount Everest:

In 2008, a new weather station was established at an elevation of around 8,000 meters. The station was coordinated by the Stations at High Altitude for Research on the Environment (SHARE). Whom also installed the Mount Everest webcam in 2011. The solar-powered weather station is situated on the South Col.

Mount Everest stretches into the upper troposphere and extends into the stratosphere. At the summit, the air pressure is approximately a third of that at sea level. The altitude exposes the summit to the swift and freezing winds of the jet stream. Whereas, wind speeds frequently reach 160 km/h (100 mph). With historical wind speeds taking place in February 2004, where they reached a speed of 280 km/h (175 mph) at the summit.

These winds can impede or pose risks to climbers, potentially propelling them into crevices or further lower air pressure and reduce available oxygen by up to 14 percent. To mitigate exposure to the strongest winds, climbers usually target a 7- to 10-day period in the spring and fall, when the Asian monsoon season is either commencing or concluding.

History of Expeditions on Everest:

The first known person to reach Everest’s summit was in 1953, which sparked increased interest among climbers. Despite significant effort and attention dedicated to expeditions, the number of individuals who had successfully summited the peak remained limited, with only about 200 people achieving this by 1987. For decades, Mount Everest posed a challenge, even for experienced climbers and large national expeditions that were the standard approach until the advent of the commercial era in the 1990s.

As of January 2023, Everest had been summited 6,338 times, but not without its share of deaths. In total there have been over 300 deaths, and currently there are more than 200 dead bodies frozen on Everest. Despite potentially longer or steeper climbs on lower mountains, Everest’s extreme elevation makes it susceptible to deadly factors, making it one of the deadliest mountains to climb.

Below is a recount of the history of expeditions on Everest:

1. Early Attempts of Climbing Everest:

In 1885, Clinton Thomas Dent, the president of the Alpine Club, proposed the feasibility of climbing Mount Everest in his book “Above the Snow Line.”

The northern approach to the mountain was uncovered during the initial 1921 British Reconnaissance Expedition led by George Mallory and Guy Bullock. Although the expedition was exploratory in nature and not geared for a full-scale ascent, Mallory led the way, becoming the first European to step onto Everest’s flanks. They managed to ascend to an altitude of 7,005 meters (22,982 feet) at the North Col.

The British returned for another expedition in 1922. Notably, George Finch employed oxygen for the first time during his climb. He achieved an impressive rate of ascent—290 meters (951 feet) per hour—and reached an altitude of 8,320 meters (27,300 feet), marking the first reported ascent above 8,000 meters.

The subsequent British expedition took place in 1924. The initial try by Mallory and Geoffrey Bruce was halted due to adverse weather conditions preventing the establishment of Camp VI. The following attempt was led by Norton and Somervell, who undertook the climb without oxygen and in favorable weather conditions. They traversed the North Face and reached the Great Couloir. Norton managed to reach an altitude of 8,550 meters (28,050 feet), although he only ascended around 30 meters (98 feet) in the final hour.

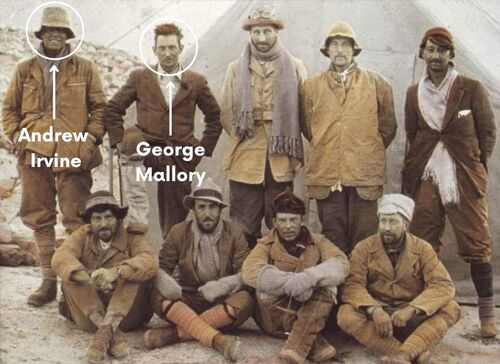

On June 8, 1924, George Mallory and Andrew Irvine embarked on an ascent to the summit using the Northeast Ridge route. Unfortunately, they never returned from their endeavor. Almost 75 years later, on May 1, 1999, the Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition located Mallory’s body on the North Face, situated in a snow basin below and west of the traditional Camp VI location. The mountaineering community has been deeply divided over whether Mallory and Irvine reached the summit or not.

Expeditions including Charles Bruce’s, and the unsuccessful attempts by Hugh Ruttledge in the 1936 and 1933 expedition, aimed to conquer the mountain from Tibet via the North Face. However, access from the north to Western expeditions was closed in 1950 when China gained control over Tibet. In the same year, Bill Tilman and a small group, including Charles Houston, Oscar Houston, and Betsy Cowles, embarked on an exploratory expedition to Everest through Nepal. The route they explored is now the standard approach to the mountain from the south.

The 1952 Swiss Mount Everest Expedition, led by Edouard Wyss-Dunant, obtained permission to attempt a climb from Nepal. They established a path through the treacherous Khumbu icefall and reached the South Col at an altitude of 7,986 meters (26,201 feet). On the southeast ridge, Raymond Lambert and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay managed to reach around 8,595 meters (28,199 feet), setting a new record for climbing altitude. The Swiss team decided to make another attempt in the autumn after the monsoon season; they reached the South Col but were compelled to retreat due to harsh winter conditions, including freezing winds.

2. First Successful Ascent by Tenzing and Hillary in 1953:

The ninth British expedition took place in 1953, under the leadership of John Hunt. Hunt chose two pairs of climbers for the summit push. The first duo, Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans, came incredibly close to the summit on May 26, 1953, reaching within 100 meters (330 feet), but had to turn back due to issues with their oxygen supply. Their efforts in trailblazing and establishing oxygen caches greatly aided the second pair.

Two days later, on May 29, 1953, the expedition made another summit attempt with the second pair: New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Nepali Tenzing Norgay. They successfully reached the summit at 11:30 am local time via the South Col route. While both climbers recognized the collective effort of the entire expedition, Tenzing later disclosed that Hillary had set foot on the summit first.

The news of the expedition’s success coincided with Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation on June 2, and London received the news on the same morning. Soon after, the Queen ordered that Hunt (a British national) and Hillary (a New Zealander) be knighted in the Order of the British Empire for their accomplishment. Tenzing, a Nepali Sherpa with Indian citizenship, was awarded the George Medal by the UK.

Hunt later became a life peer in Britain, while Hillary became a founding member of the Order of New Zealand. In Nepal, both Hillary and Tenzing were also honored. Statues were erected in their names in 2009, and in 2014, peaks were named after them—Hillary Peak and Tenzing Peak.

3. 1950s–1960s Ascents:

During the 1950s and 1960s, several notable ascents were made on Mount Everest. In 1956, Ernst Schmied and Juerg Marmet successfully reached the summit, followed by Dölf Reist and Hans-Rudolf von Gunten in 1957.

China’s Wang Fuzhou, Gonpo, and Qu Yinhua achieved a significant milestone by making the first reported ascent via the North Ridge in 1960. Additionally, Jim Whittaker became the first American to summit Everest, accomplishing this feat alongside Nawang Gombu in the 1963 American Everest Expedition.

4. 1970s Achievements and Challenges:

The 1970s witnessed a mix of achievements and challenges on Everest. Japanese mountaineers embarked on major expeditions in this decade, attempting new routes and even skiing down parts of the mountain.

Japanese climber Yuichiro Miura made history by skiing down Everest’s South Col, although he suffered severe injuries during the descent. In 1975, Junko Tabei from Japan achieved a significant milestone as the first woman to successfully summit Mount Everest.

5. Winter Himalaism and Polish Ascents (1979/80)

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the focus shifted towards winter ascents and Polish achievements on Everest. In 1980, under the leadership of Andrzej Zawada, a Polish team accomplished the remarkable feat of the first winter ascent of Mount Everest. This achievement marked the beginning of a new era known as Winter Himalaism, where Polish climbers specialized in conquering high peaks during winter conditions. This success spurred a series of winter ascents on other 8,000-meter peaks, earning Polish climbers the nickname “Ice Warriors.”

6. 1996 Disaster and Safety Concerns:

The 1996 Everest disaster took place on 10 and 11 May, resulting in the death of eight climbers due to a blizzard during their summit attempt. In total, 15 lives including the famous Green Boots (Tsewang Paljor), were lost on Everest during that season, raising concerns about the commercialization of climbing and the safety of guided expeditions.

Journalist Jon Krakauer’s book, “Into Thin Air,” shared his firsthand experience of the disaster and ignited discussions about guiding practices. Guide Anatoli Boukreev, criticized in Krakauer’s account, responded with “The Climb.” The debate prompted reflection within the climbing community and earned Boukreev recognition for his rescue efforts.

During the disaster, Madan Khatri Chetri performed the highest helicopter rescue on Everest, to save Beck Weathers and Makalu Gau at 6,400 meters.

7. 2006 Mountaineering Season:

The 2006 climbing season saw 12 fatalities on Everest. The death of David Sharp prompted debates on climbing ethics, as his plight and the lack of intervention by other climbers raised questions about the responsibilities of fellow mountaineers.

In contrast, the season featured the extraordinary rescue of Lincoln Hall, who was left by his team for dead but miraculously survived and was saved after days of exposure on the mountain.

8. 2014 Avalanche and Achievements:

A devastating avalanche hit Everest on 18 April 2014, claiming the lives of sixteen Nepali guides and injuring nine others. Amidst this tragedy, young climber Malavath Purna became the youngest female to conquer the summit.

Notably, one team utilized a helicopter to reach Camp 2, circumventing the Khumbu Icefall, and eventually reaching the summit. This season also saw significant summits from both the Chinese (Tibet region) and Nepalese sides.

Sherpa Strike of 2014:

The 2014 avalanche that struck Mount Everest, resulted in one of the most deadly incidents ever seen by the Everest climbing community. The avalanche claimed the lives of 16 Sherpas guides in Nepal. Following this heart-wrenching disaster, a significant number of Sherpa climbing guides decided to halt their activities, while most climbing companies also suspended operations out of respect for the Sherpa community.

Despite some climbers still being interested in continuing their ascents, the controversy surrounding the event made it impractical to proceed with climbs during that particular year. One of the factors that triggered the Sherpas’ decision to stop working was the imposition of unreasonable demands by clients during their climbs and lack of support from the Nepali Government.

9. 2015 Avalanche and Earthquake Impact:

The anticipation for a record-breaking climbing season in 2015 was shattered by the deadly earthquake that hit Nepal on April 25, triggering a fatal avalanche at Everest Base Camp. This event, followed by multiple aftershocks, led to the cancellation of all climbs and the deaths of climbers who were trapped or evacuated. The tragedy also reflected the wider impact of the earthquake on Nepal, causing widespread devastation and loss of life.

10. 2018: A Record-Setting Year:

In 2018, a historic number of climbers – 807 in total – successfully summited Mount Everest. This included 563 from Nepal and 240 from the Chinese Tibet side. This marked a new record for total summits in a year, aided by clear weather during the spring climbing season. Among the summiteers was Xia Boyu, a double-amputee.

However, seven climbers lost their lives, highlighting the challenges of overcrowding and environmental concerns. The passing of Elizabeth Hawley, the creator of the Himalayan Database, the unofficial record keeper for climbs in the Nepalese Himalaya, was a notable event as well.

11. 2019: Challenges and Triumphs:

The 2019 climbing season was marked by both challenges and remarkable achievements. Images of long queues of climbers and sensational reports of climbers passing deceased mountaineers drew global attention.

While Nepal issued 381 climbing permits, China also authorized numerous permits for the northern routes. Climber Kami Rita’s double summit within a week made headlines, and despite the record number of summits (891), the season also saw a higher number of fatalities due to natural dangers and medical issues exacerbated by the extreme altitude.

12. 2020s: Pandemic Impact and Notable Ascents:

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the closure of Everest to foreign climbing groups both from the north and south route in 2020. In the midst of the pandemic, a Chinese survey team scaled Everest from the North side, aiming to re-measure its height.

A milestone was achieved in 2022, as an all-Black team successfully summited Everest, showcasing diversity in mountaineering. In 2023, the achievements continued with the second deaf person, Muhammad Hawari Hashim, and an American deaf couple, Shayna Unger and Scott Lehmann, reaching the summit.

Climbing Routes and Notable Areas on Everest:

Mount Everest boasts two primary climbing routes: one is the southeast ridge originating from Nepal, and the other is the north ridge stemming from Tibet. There also exist numerous alternate climbing routes on Everest, although these are less frequently used. Between the two primary paths, the southeast ridge stands out as the more manageable and commonly chosen option. Notably, this was the path taken by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953, marking it as the first recognized route among the fifteen leading to the summit by 1996.

Southeast Ridge Climbing Route:

The Southeast Ridge or South Col route on Everest commences with a trek to Everest Base Camp (EBC) at an altitude of 5,380 meters on the south side of the mountain, situated in Nepal. Expeditions usually start by flying into Lukla at 2,860 meters from Kathmandu and then proceeding through Namche Bazaar. The journey to Base Camp takes around six to eight days, allowing climbers to acclimatize to the high altitude and prevent altitude sickness. Supplies and climbing gear are transported to Base Camp using yaks, and human porters.

Climbers spend a few weeks at Base Camp acclimatizing and preparing for the climb. During this period, Sherpas set up ropes and ladders in the dangerous Khumbu Icefall, known for its seracs, crevasses, and moving blocks of ice. Climbers often begin their ascent before dawn to mitigate the risks posed by shifting ice blocks.

Beyond the Icefall at an elevation of 6,065 meters lies Camp I. Climbers progress through the Western Cwm, a flat glacier valley with gradual slopes, reaching Camp II (Advanced Base Camp) at 6,500 meters by the Lhotse face’s base. From Advanced Base Camp, climbers use fixed ropes to ascend the Lhotse face, reaching Camp III at 7,470 meters, then moving on to Camp IV on the South Col at 7,920 meters.

Summit efforts start around midnight at Camp IV, with climbers aiming for a 10 to 12-hour ascent, covering 1,000 more meters. Notable points are “The Balcony” at 8,400 meters and the South Summit at 8,750 meters. The knife-edge southeast ridge includes the risky “Cornice traverse” and the challenging Hillary Step, a 12-meter rock wall.

Beyond the Hillary Step, a loose rocky section with fixed ropes leads to the summit. Climbers briefly stay before descending to Camp IV to avoid weather issues or oxygen deficiency.

North Ridge Climbing Route:

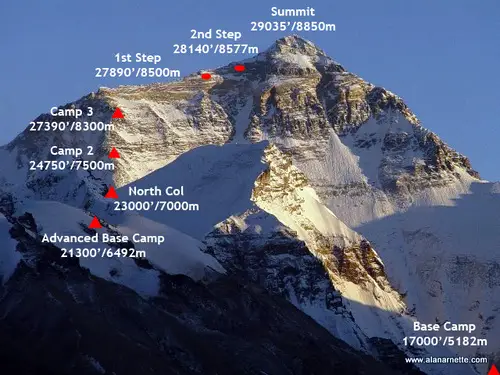

The north ridge routs on Everest, starts in Tibet. Expeditions embark on a trek to the Rongbuk Glacier, where they establish base camp at an elevation of 5,180 meters on a gravel plain just below the glacier. Climbers ascend the medial moraine of the east Rongbuk Glacier to reach Camp II, located near the base of Changtse at approximately 6,100 meters.

Advanced Base Camp (ABC), known as Camp III, is positioned beneath the North Col at 6,500 meters. Ascending further to Camp IV on the North Col involves traversing the glacier and utilizing fixed ropes to reach an elevation of 7,010 meters. From the North Col, climbers ascend the rocky north ridge to establish Camp V around 7,775 meters. The route then leads across the North Face in a diagonal climb to the base of the Yellow Band, culminating at the site of Camp VI at 8,230 meters. This serves as the launching point for the final summit push.

The most demanding segment of the climb, the Second Step, necessitates an ascent from 8,577 to 8,626 meters. The Second Step includes a permanent climbing aid known as the “Chinese ladder,” which was installed in 1975 and has been utilized by nearly all climbers on the route. Beyond the Second Step, climbers tackle the less significant Third Step, ascending from 8,690 to 8,800 meters. After conquering these steps, the summit pyramid is ascended via a 50-degree snow slope.

Summit of Everest:

Described as being no larger than a dining room table, the summit of Mount Everest is adorned with layers of snow over ice and rock. The rock summit consists of Ordovician limestone, constituting a type of low-grade metamorphic rock.

Beneath the summit lies an area aptly referred to as the “Everest’s Rainbow Valley,” where deceased climbers are frozen on the slopes still wearing their brightly colored winter gear. Moreover, once climbers pass approximately 8,000 meters (26,000 feet) they are officially in the “death zone,” characterized by a higher chance of fatality and limited oxygen due to the diminished atmospheric pressure.

From the summit, the mountain’s contours slope downward along its three primary faces: the North Face, the South-West Face, and the east’s Kangshung Face.

Death Zone on Everest:

Climbers who aim to conquer the summit must navigate the death zone of Everest, which is situated above altitudes of 8,000 meters (26,000 feet). The harsh temperatures plummet to extreme lows, posing the risk of frostbite to any exposed body parts. The terrain, covered in frozen snow, increases the potential for slips and falls, while ferocious high-altitude winds add an additional layer of danger.

A critical hazard in this zone arises from the significantly reduced atmospheric pressure. The uppermost point of Everest experiences merely a third of sea-level pressure, resulting in only about a third of the usual oxygen available for breathing. The repercussions of the death zone’s effects are so profound that covering a mere 1.72 kilometers (1.07 miles) from the South Col to the summit can take climbers up to 12 hours.

Even at base camp, the limited partial pressure of oxygen had a tangible impact on blood oxygen saturation, which fell to between 85 and 87 percent. Blood samples taken at the summit exhibited critically low oxygen levels. This scarcity of oxygen leads to a significantly heightened breathing rate, often ranging from 80 to 90 breaths per minute, resulting in exhaustion.

The lack of oxygen, combined with exhaustion, intense cold, and the various hazards of climbing, contributes to the mountain’s high mortality rate. Those unable to walk due to injury or fatigue face significant peril, as rescue by helicopter is seldom feasible, and carrying an incapacitated individual down the mountain is extremely risky. As of 2015, over 200 bodies remain on the mountain, a somber reminder of the risks involved. Even along the standard climbing routes, it is not uncommon to encounter deceased climbers.

Dangers of High Altitude Sickness on Everest:

High altitude sickness, also known as acute mountain sickness (AMS), poses a significant challenge for climbers on Mount Everest and other high-altitude environments. As climbers ascend to extreme heights, the decreasing levels of oxygen and reduced atmospheric pressure can lead to AMS, which manifests through various symptoms.

At altitudes above 2,500 meters (8,200 feet), the body’s ability to adapt to the decreasing oxygen levels becomes crucial. AMS symptoms can range from mild to severe and include headaches, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and shortness of breath. In more severe cases, individuals may experience confusion, loss of coordination, and persistent coughing. Climbers trying to ascend Everest are particularly susceptible to AMS due to the extreme altitude of the mountain.

The condition occurs due to the body’s inability to acclimatize quickly enough to the thinning air. This leads to a shortage of oxygen in the body’s tissues, triggering a range of responses. Preventive measures, such as gradual acclimatization, proper hydration, and cautious ascent schedules, are essential to mitigate the risk of AMS. Climbers often spend time at various altitudes to allow their bodies to adjust gradually and build red blood cell count.

The effects of high altitude on the brain, even after descending to lower levels, can be significant. Cognitive impairment, including delayed and lethargic thought processes (bradypsychia) and hallucinations, can occur. Some studies suggest altered brain structure among high-altitude climbers, raising concerns about potential permanent brain damage. The ongoing research explores the impact of high altitude on the brain and the potential long-term consequences.

Using Supplemental Oxygen on Mount Everest:

To mitigate the chances of High Altitude Sickness, climbers typically use bottled oxygen. Whereas, at altitudes surpassing 8,000 meters (26,000 feet), most expeditions employ supplemental oxygen masks and tanks to combat the diminishing levels of oxygen. While ascending without supplementary oxygen is possible, it is undertaken by highly skilled mountaineers and comes with heightened risk.

The thin air, combined with harsh weather, freezing temperatures, and steep terrain, demands swift, accurate decision-making that can be hindered by low oxygen levels. Roughly 95% of summiting climbers utilize bottled oxygen to reach the top, yet a small percentage of climbers have achieved the summit without supplemental oxygen. However, the mortality rate for climbers attempting the summit without extra oxygen is twice that of those who use it.

The debate surrounding the use of bottled oxygen on Everest dates back to the 1920s. Early instances of its use were met with skepticism due to the belief that it was unsportsmanlike. The discussion persisted for years, and even as the first successful summit was achieved in 1953 by Tenzing Norgay and Hillary with the aid of bottled oxygen, differing opinions persisted.

In 1978, Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler broke tradition by reaching the summit without supplemental oxygen, prompting a shift in the climbing community’s perspective. In 1980, Messner accomplished the feat solo, igniting a movement among purists who believed that Everest should be climbed without extra oxygen.

The 1996 Everest disaster, however, amplified the debate further. Jon Krakauer’s “Into Thin Air” criticized the use of bottled oxygen for enabling unqualified climbers to attempt the summit, contributing to dangerous situations and fatalities. The disaster also highlighted the role of guides in using bottled oxygen as Krakauer put blame on guide Anatoli Boukreev for not using bottled oxygen during the expedition.

Climbing Seasons on Mt. Everest:

The majority of ascent attempts occur in May, preceding the onset of the summer monsoon season. As the monsoon period nears, the jet stream migrates northward, resulting in reduced wind speeds at higher altitudes on the mountain. While some endeavors are occasionally undertaken in September and October, after the monsoons, when the jet stream briefly shifts northward again, the snow accumulation caused by the monsoons and the less predictable weather patterns during the latter stages of the monsoon season render climbing exceedingly challenging.

Nonetheless here are the main climbing seasons for Mount Everest:

1. Spring Season (Pre-Monsoon):

This is the most popular and well-known climbing season on Everest. It usually spans from late April to early June. During this period, the weather becomes relatively stable, and the jet stream shifts northward, reducing the high winds that can make climbing difficult. The warmer temperatures also lead to melting snow and ice, making the conditions more manageable. The majority of successful summits occur during this spring window.

2. Autumn Seasons Climbing:

While spring remains the preferred season, Mount Everest has also witnessed ascents during the autumn period, often referred to as the “post-monsoon season”. For instance, in 2010, Eric Larsen and a team of five Nepali guides achieved a successful autumn summit, marking a decade since the last such feat. Although riskier due to the presence of newly fallen and potentially unstable snow, the autumn season has its attractions. The increased snowfall can cater to winter sports like skiing and snowboarding, adding to its allure.

In October 1976, Chris Chandler and Bob Cormack accomplished a significant feat as part of the American Bicentennial Everest Expedition, becoming the first Americans to conquer Everest during the autumn season. In recent times, summer and autumn have witnessed a rise in skiing and snowboarding attempts on the mountain.

Additionally, even though some attempts have been made during winter, it is an unpopular season for Everest ascents due to a combination of severe cold, strong high-altitude winds, and shorter daylight hours. By January, the peak experiences 170 mph (270 km/h) winds and an average summit temperature of approximately −33 °F (−36 °C).

Well Known Everest Climbers:

Among the famous climbers on Everest, Sir Edmund Hillary of New Zealand stands as one of the first two individuals to conquer Everest’s summit in 1953, etching his name in mountaineering history. Alongside Hillary was Tenzing Norgay, whose daring ascent marked a pivotal moment for Nepal and the Sherpa community.

Junko Tabei from Japan, accomplished the extraordinary feat of becoming the first female to stand triumphantly on Everest’s peak in 1975, shattering gender norms and inspiring generations of women climbers.

Italy’s Reinhold Messner, an icon in the mountaineering world, introduced a new type of climbing by summiting Everest without supplemental oxygen in 1978.

From the United States, Erik Weihenmayer became the first blind person to summit Everest in 2001. Jordan Romero, another American climber, left an indelible mark by becoming the youngest person to complete the Seven Summits, including Everest, at just 15 years old.

From Nepal, Nirmal Purja, whose ambitious project to summit all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks in less than 7 months captured global attention, redefining rapid ascents. Kami Rita Sherpa, a revered sherpa, achieved an astounding record of summiting Everest a record 28 times as of 2023.

Pasang Lhamu Sherpa from Nepal, the first Nepali woman to summit Everest and survive, stands as a testament to the strength and determination of women in mountaineering.

These Mount Everest climbers, each with their unique stories of courage and perseverance, have etched their names into history. However, the true unsung heroes of Everest are the Sherpas.

Sherpas of Everest:

Mount Everest Sherpas are indigenous people of the Himalayas, and play an indispensable role in climbing the tallest mountain in the world. Through generations of living at high altitudes, their bodies have adapted to cope with low oxygen levels, allowing them to ascend Everest’s peaks with relative ease. Their lung capacity, red blood cell count, and efficient oxygen utilization set them apart from climbers who hail from lower elevations.

Moreover, Sherpas’ exceptional climbing prowess is a result of a lifetime spent traversing these mountains. Starting from a young age, they accompany expeditions, honing their skills as they navigate the challenging terrain. Their deep understanding of the mountain, unpredictable weather, and hidden dangers ensures safer journeys for all. In addition to their mountaineering expertise, Sherpas provide logistical support, carrying heavy loads, setting up camps, and guiding climbers through treacherous sections.

The vital role of Sherpas extends beyond their climbing proficiency; it encompasses their rich cultural heritage, unwavering dedication, and spirit of camaraderie. As the backbone of Everest expeditions, they not only facilitate ascents but also share the legacy of the mountains.

Aviation on Everest:

Mount Everest has also had its fair share of aviation accomplishments. Dating back to the 1930s, adventure enthusiasts have been fascinated with the Himalayan giant. Below are notable aviation feats on Mt. Everest.

1. First Flight Over Everest (1933)

In 1933, Lucy, Lady Houston, an affluent British former showgirl, backed the Houston Everest Flight initiative. Under the leadership of the Marquess of Clydesdale, a fleet of aircrafts soared over the summit, striving to capture images of the uncharted terrain.

2. First Climb and Paragliding Descent (1988)

On September 26, 1988, Jean-Marc Boivin became the first person to descend Everest via paraglider. This extraordinary feat secured records for the swiftest descent of the peak and the highest paraglider flight. Boivin’s accomplishment came after a difficult ascent, which led him to utter exhaustion by the time he reached the summit. He recollected, “I was tired when I reached the top because I had broken much of the trail, and to run at this altitude was quite hard.” Launching his paraglider, he dashed 18 meters (60 feet) down a steep 40-degree slope to touch down at Camp II, positioned at 5,900 meters (19,400 feet), completing the descent in a mere 12 minutes.

3. Flying Over Everest in a Hot Air Balloon (1991)

In 1991, a hot air balloon expedition soared over the peak of Mount Everest. The flight involved two balloons manned by four individuals: Andy Elson and Eric Jones in one, and Chris Dewhirst and Leo Dickinson in the other. This historic event was chronicled by Dickinson in his book “Ballooning Over Everest”.

Specially modified to function at altitudes of up to 12,000 meters (40,000 feet), the hot air balloons granted a panoramic vista of Everest, with one of Dickinson’s photographs of the mountain being hailed as the “best snap on Earth”. Remarkably, Dewhirst has offered an opportunity for enthusiasts to partake in a similar adventure for a cost of $2.6 million per passenger.

4. Helicopter Summits on Everest (2005)

In 2005 French pilot Didier Delsalle landed his Eurocopter AS350 B3 helicopter on the peak of Mount Everest. Although his mission necessitated a mere two-minute touchdown to secure the official record recognized by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), Delsalle extended his stay to approximately four minutes! Delsalle’s remarkable feat involved keeping the rotors engaged during the landing, avoiding complete reliance on the snow for support. He set new world records for both the highest landing and take-off via rotorcraft.

5. Paragliding From the Summit of Everest (2011)

In an extraordinary display of skill, Nepali adventurers Lakpa Tsheri Sherpa and Sano Bapu Sunuwar paraglided from Everest’s summit to Namche Bazaar in a mere 42 minutes on May 21, 2011. Instantly making them some of the most famous Sherpas on Everest.

Their feat continued as they hiked, biked, and kayaked all the way to the Indian Ocean. With their trip culminating at the Bay of Bengal by June 27, 2011. Effectively becoming the first to achieve an uninterrupted descent from Everest’s summit to the sea. This unprecedented endeavor holds added significance due to Bapu’s lack of previous climbing experience and Lakpa’s unfamiliarity with kayaking and swimming.

6. Helicopter-Assisted Ascent (2014)

In 2014, mountaineer Wang Jing used a helicopter to bypass the treacherous Khumbu Icefall, aiding her team’s climb to Everest’s summit. Wang’s approach stirred controversy and debate within the mountaineering community regarding the integrity of her climb. Following investigation by Nepal, Wang admitted to flying to Camp 2 due to the impassable icefall, ultimately bringing to light discussions about helicopter use in the realm of mountaineering.

7. Transportation via Helicopters Increase (2016)

By 2016 a significant increase in helicopter usage, notably for the more efficient transport of materials across the perilous Khumbu icefall had taken place. The employment of helicopters not only enhanced operational efficiency but also contributed to reducing risks for icefall porters.

After the tragedy in the icefall in 2014 and the subsequent earthquake in 2015, helicopters played a crucial role in rescue operations and in optimizing transportation to Camp 1. Bell’s 412EPI helicopter underwent rigorous testing near Everest, flying as high as 6,100 meters (20,000 feet) altitude and hovering at 5,500 meters (18,000 feet).

The Birth of Commercial Climbing on Everest:

Jon Krakauer marked the commencement of Everest’s commercialization in 1985, when a guided expedition, led by David Breashears and including Richard Bass, a 55-year-old affluent businessman with only four years of climbing experience, successfully reached the summit. By the early 1990s, numerous companies were providing guided tours to the mountain. Rob Hall of Adventure Consultants, who tragically perished in the 1996 disaster, had guided 39 clients to the summit prior to that incident.

By 2016, the majority of guiding services were priced between US$35,000 and US$200,000. Opting for a “celebrity guide,” typically an established mountaineer with extensive climbing experience and multiple Everest summits, could incur costs exceeding £100,000 as of 2015.

Additionally, the cost to climb Everest can vary significantly beyond the guiding service. While it’s technically feasible to reach the summit with minimal added costs, “budget” travel agencies offer logistical assistance for such journeys. A basic support package, encompassing base camp meals and bureaucratic aspects like permits, could cost as low as US$7,000 as of 2007. However, this approach is considered dangerous and deadly, as demonstrated by the case of David Sharp in 2006.

Dangers of Commercialization:

The extent of Everest’s commercialization has sparked recurring criticism. Jamling Tenzing Norgay, son of Tenzing Norgay, commented in 2003 that his late father would be astounded by the fact that affluent adventurers lacking climbing experience now routinely achieve the summit, stating, “The spirit of adventure has faded. People ascend because they paid someone $65,000, not because they truly climbed the mountain. It’s selfish and jeopardizes others’ lives.”

Shriya Shah-Klorfine exemplifies this trend; during her 2012 summit attempt, she required instruction on using crampons. Paying at least US$40,000 to a newly established guiding company for the trip, she tragically succumbed due to oxygen depletion after a continuous 27-hour climb.

By 2015, Nepal contemplated mandating climbing experience for climbers, aiming to enhance safety and revenue. A challenge to this proposal lies in the fact that low-budget firms profit from escorting inexperienced climbers, which may discourage the implementation of the requirement. Individuals turned away by Western companies often find alternate firms willing to accommodate them at a price – usually with the expectation that they would return home shortly after reaching base camp or part way up the mountain.

Issue of Theft and Crime with the Commercialization of Everest:

With the commercialization of the mountain, theft and crime have also increased. Climbers have recounted instances of life-threatening thefts occurring at their supply caches. A case from May 2006 involves Vitor Negrete, the first Brazilian to conquer Everest without oxygen, who was a member of David Sharp’s expedition. Tragically, Negrete lost his life during his descent, and the theft of equipment and provisions from his high-altitude camp are thought to have played a role in his demise.

Michael Kodas, in his book titled “High Crimes: The Fate of Everest in an Age of Greed” (2008), further elaborates on this issue. He describes unethical conduct by guides and Sherpas, the prevalence of prostitution and gambling at the Tibet Base Camp, instances of fraud linked to the sale of oxygen canisters, and climbers deceiving others by soliciting donations under the guise of cleaning up the mountain from debris.

The Chinese side of Everest in Tibet gained a reputation of being “out of control” in 2007 when a Canadian climber had his gear stolen and was abandoned by his Sherpa. Fortunately, another Sherpa came to his aid, ensuring his safe descent and providing spare equipment. Reports of missing oxygen bottles, which carry substantial value, have also surfaced, given the hundreds of climbers passing by tents, making theft prevention challenging. In the late 2010s, the occurrences of oxygen bottle thefts from camps became increasingly frequent.

Mount Everest and Extreme Sports:

During the 1970s, Yuichiro Miura achieved the distinction of being the first person to ski down Everest. He made a descent of nearly 1,300 vertical meters (4,200 feet) from the South Col before sustaining severe injuries in a fall. In 2001, Stefan Gatt and Marco Siffredi snowboarded down Mount Everest.

Notable Everest skiers include Davo Karničar of Slovenia, who completed a full top-to-south base camp descent in 2000, Hans Kammerlander of Italy, who accomplished a descent on the north side in 1996, and Kit DesLauriers of the United States, who achieved a similar feat in 2006.

In 2006, Swede Tomas Olsson and Norwegian Tormod Granheim skied down the north face together. Tragically, Olsson lost his life when his anchor failed during a rappel down a cliff in the Norton couloir at around 8,500 meters, resulting in a fall of approximately two and a half kilometers. Granheim managed to ski down to camp III.

Gliding descents of various forms have been gradually gaining popularity, known for their rapid descents to lower camps. In 1986, Steve McKinney led an expedition to Everest and became the pioneer to hang-glide off the mountain. Frenchman Jean-Marc Boivin achieved the first paraglider descent from Everest in September 1988. He completed a swift descent from the south-east ridge to a lower camp within minutes. In 2011, two Nepalis executed a gliding descent from the Everest summit, covering a distance of 5,000 meters (16,400 feet) in just 45 minutes.

On May 5, 2013, Red Bull sponsored Valery Rozov’s successful BASE jump off the mountain while donning a wingsuit, setting a new record for the world’s highest BASE jump in the process.

Religion on the Mountain and Surrounding Areas:

The southern region of Mount Everest holds a significant place among the designated “hidden valleys” of refuge outlined by Padmasambhava, a ninth-century Buddhist saint known as the “lotus-born.”

Situated near the base of Everest’s north side, Rongbuk Monastery is often referred to as the “sacred gateway to Mount Everest,” offering some of the most breathtaking views in the world. For Sherpas residing on Everest’s slopes in Nepal’s Khumbu region, Rongbuk Monastery holds immense importance as a pilgrimage site. It can be reached after a few days of travel across the Himalayas through Nangpa La pass.

Miyolangsangma, a Tibetan Buddhist deity known as the “Goddess of Inexhaustible Giving,” is believed to have resided at the summit of Mount Everest. According to Sherpa Buddhist monks, the mountain serves as Miyolangsangma’s palace and playground, with climbers considered somewhat like uninvited guests upon arrival.

The Sherpa community also holds the belief that Mount Everest and its surroundings are imbued with spiritual energy, and thus, individuals should exhibit reverence when traversing this sacred landscape. In this realm, the karmic consequences of one’s actions are heightened, urging the avoidance of impure thoughts.

Issue of Waste Management on Mount Everest:

In 2015, the president of the Nepal Mountaineering Association issued a warning regarding the critical levels of pollution, human waste and trash on Mount Everest. Approximately 12,000 kilograms (26,500 pounds) of human excrement is left behind on the mountain each climbing season.

Human waste is scattered along the path leading to the summit, rendering the four sleeping areas along the route up Everest’s southern side littered with human excrement. Climbers have traditionally dealt with their waste either by burying it in snow holes they manually dug, discarding it into crevasses, or simply defecating wherever convenient.

Positioned at around 5,500 meters (18,000 feet), Base Camp is the most active of all camps on Everest, serving as a site for climber acclimatization and rest. To address this issue, expeditions in the late 1990s began using makeshift toilets crafted from blue plastic barrels with a toilet seat and enclosure.

The human waste problem is compounded by the presence of less biodegradable waste, including used oxygen tanks, abandoned tents, empty containers, and bottles. The Nepali government now mandates that each climber must carry out eight kilograms of waste when descending the mountain.